Political divination is a new national pastime, with prominent forecasters playing the part of celebrated oracles. Fueled by massive stakes and bitter partisanship, a new breed of high-profile election handicappers have hooked the country on their highly addictive brand of data, cheerfully shoveling an endless stream of poll-driven predictions into the maw of an insatiable public.

But as the slowly unfolding results of Tuesday’s election have shown, the authors of those predictions are far from omniscient. If some of their bets for the 2020 race seem increasingly on target, others — notably, predicting a win for Biden in Florida and saying Sen. Susan Collins would probably lose in Maine — seem far off, a jarring disconnect for a public that put its faith in the data-driven prognosticating emanating from outlets including FiveThirtyEight, the New York Times, and the Economist. (Here's a closer look at how the numbers added up.)

The forecasters, for their part, have gamely defended the accuracy of their work, telling the public it misconstrues the information they present or that they never pretended to be perfect. A tweet by Nate Silver, perhaps the field’s most prominent figure, telling anxious Democrats to “have a glass of wine or whatever and chill out about the polls” seemed to many readers like a promise that their preferred candidate would win handily. When closer-than-expected results left some people feeling misled, however, Silver didn’t appear to do much soul-searching.

“If they’re coming after FiveThirtyEight,” he said on a podcast the day after the election, “then the answer is, Fuck you, we did a good job!”

But beyond accuracy, this race raises another, potentially more important, concern about America’s prediction obsession: that endless consumption of poll data — updated, analyzed, dissected, and promoted on TV, the web, and even in partisan fundraising efforts — distorts the entire political process, affecting the behavior of both voters and politicians in troublingly unforeseeable ways.

“I don't think it's a good thing for democracy to be so obsessed with polls,” said David Rothschild, an economist who studies polling and public opinion and who has done election forecasting in the past. “I worry it enhances horse race–style coverage of elections and skews people's expectations, while distracting from policy, which is what really matters.”

Forecasts are the products of complex mathematical simulations based on an array of polling data, often in combination with other factors such as the state of the economy. They produce what amounts to a very highly educated guess, not a confirmed take-it-to-the-bank fact. Yet the media, the political class, and voters often attribute to those forecasts the same degree of certainty that they would to NFL scores on a Monday morning.

Political scientists and statisticians point to a wide range of factors that could undermine a forecast’s accuracy. The polls they depend on may reflect a skewed sample of the population; they may not be able to fully account for shifts in the demographics of the electorate; and as for respondents, they may change their minds on their way to the voting booth.

Those problems could be compounded across a number of similar states — such as what happened in 2016, when unexpected wins in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania propelled Donald Trump to the presidency. It turns out that accurately predicting who will win individual contests in a nation of 325 million people — as opposed to measuring public opinion in a broader context — is exceedingly difficult and, experts posit, perhaps not what polling is best at.

One glaring problem is that these predictions are not what people frequently assume them to be. A projection that, for example, Joe Biden has a 75% chance of winning a given state means that of the hundreds or thousands of simulations analysts ran, three quarters resulted in his victory. What voters often overlook is that the same forecast means Biden loses that state a quarter of the time — and might never win by more than a razor-thin margin.

“Essentially,” said Solomon Messing, the chief scientist at Acronym, “it makes it sound like the candidate is a slam dunk to most people.”

That can have big consequences. After Donald Trump’s surprising Electoral College victory in 2016, Messing studied the way polling influences voter behavior. He found that hyper-confidence in an election outcome makes people less likely to vote — why bother, the thinking goes, if your candidate already has it sewn up — and that the effect seems larger among Democratic voters than Republicans. Forecasts, he found, seem to bolster that confidence.

“Forecasting increases certainty about an election’s outcome, confuses many, and decreases turnout,” the study that Messing coauthored said. The ensuing media coverage of that forecasting, meanwhile, tends to favor the leading candidate, which, in the case of 2016, “raised questions” about whether the forecasts themselves contributed to Trump’s win.

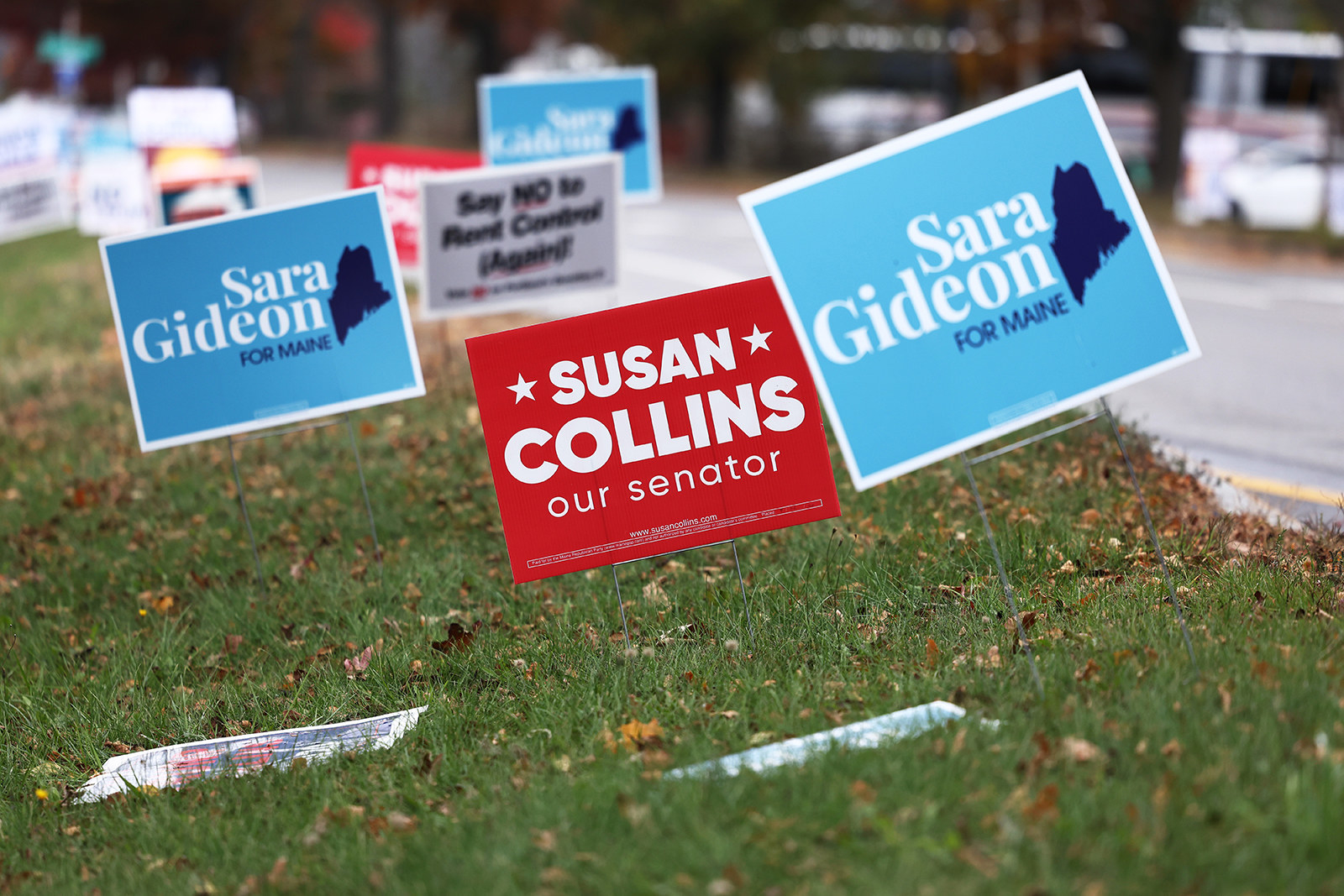

Lonna Atkeson, a political scientist at the University of New Mexico and a member of the MIT Election Data and Science Lab, said that effect may have played a role in the Maine senate race. The challenger, Sara Gideon, led the incumbent, Susan Collins, in every major poll. Instead voters chose Collins, and it wasn’t even close. As of late Wednesday, when Gideon conceded, Collins was up by more than 7 points.

“They were way off,” said Atkeson, who noted that the same pollsters appear to have correctly predicted the presidential vote in the state. “What happened in Maine? Did the polling push voters in more urban, Democratic areas to come out less for Gideon?”

She and other experts point to such situations as evidence that forecasts cannot accurately project specific voting outcomes, no matter how much the public would like them to, nor can they fully account for the impact of variables like the spread of misinformation on social media, voter intimidation efforts, or massive mail-in balloting during a pandemic.

It’s not even clear, in many cases, that pollsters are reaching the right mix of people. The sheer number of polls conducted during every campaign cycle — focused on everything from presidential preference to county-level ballot measures — leaves some voters, especially in swing states, feeling overwhelmed by incessant inquiries via phone, text message, and email. Experts say there is some evidence to suggest that the same, relatively small group of people responds to polls over and over, giving their opinions disproportionate prominence, while other cohorts are underrepresented. Pollsters try to adjust for those shortcomings with various methodologies, but it’s impossible to verify their accuracy.

“A big worry in political polling is that there are a group of people — distrustful of the media, academia, science, etc. — who do not want to engage with pollsters and survey research,” said Neil Malhotra, a professor of political economy at Stanford.

Rick Ector, a firearms instructor from Detroit who voted for Trump, told BuzzFeed News that he understands why people like him blow off inquiries from pollsters. “If we get a call from some agency asking us who we are voting for and we don’t know this person or where they are calling from and what they will do with that information, there’s high risks and stakes involved,” he said. “People put themselves at risk for getting targeted.”

Jason Chatwell, a Trump voter in Kouts, Indiana, said he goes even further. “A lot of times I will say the opposite of what I’m really going to do if I get polled,” he said. “Mainly because I don’t trust anybody."

Where polls are both more accurate and useful, said Sunshine Hillygus, a professor of political science and public policy at Duke University, is at measuring public sentiment, across a broad swath of the American public, on issues such as universal healthcare or the Green New Deal.

According to Atkeson, polling data focused on voting outcomes tends to push the public conversation away from policy and may discourage candidates from even expressing their positions on important issues. With Biden leading Trump by high single-digit and low double-digit margins in nearly every national poll throughout the late summer and early fall, Atkeson said, there was little incentive for him to take risks by talking about his own plans. Instead, he mostly stuck to criticizing the incumbent for his handling of the coronavirus.

“I know Biden has policies out there somewhere, but as far as I can tell all he talked about was COVID, COVID, COVID,” said Atkeson. “You can see why they chose that strategy.”

Candidates also have become adept at using polling data for other ends, such as fundraising. Although Mark Kelly surveyed extremely strongly overall against incumbent Martha McSally in the Arizona Senate race, his campaign pursued an underdog strategy, sending supporters cherry-picked data from less favorable polls in order to generate donations.

“Three polls show Mark Kelly statistically tied with Martha McSally in Arizona,” read the subject line of one such email sent Oct. 14. In fact, polls taken at that time showed him up by as much as 11 points. It seemed to work: By Election Day, Kelly had raised $33 million more than his opponent. As of Thursday morning, Kelly led by a comfortable margin of 4.2 percentage points, although the race has not yet been called.

Over the past dozen years, polling has blossomed from a service providing data to campaigns and news outlets to a media industry in its own right. Forecasters strive to be accurate not only for accuracy’s sake, but also because of the financial incentives driving their own businesses, which extend far beyond political races. The irony is that this kind of data-driven analysis, which Silver has said he developed as an alternative to the subjective, narrative cast of so much horse race political coverage, has instead breathed new life into horse race coverage.

Some have suggested that the most recent polling debacle could spell the end of polling as we know it. But there were similar calls after the 2016 election, too. Most observers doubt that kind of change is coming anytime soon.

“I don't see the pollsters go away,” said Atkeson. “It's a great story and one that keeps giving. Every day you get to run new models. The polling itself becomes part of the election narrative.” ●

Correction: Solomon Messing is the chief scientist at Acronym. His job title was misstated in a previous version of this post.