This is Part 7 of a BuzzFeed News investigation.

To read the other articles in this series, click here.

Top executives at the World Wide Fund for Nature personally reviewed detailed evidence that anti-poaching forces funded by the charity raped and tortured innocent people — more than a year before BuzzFeed News exposed similar abuses, documents show.

A 60-page WWF-commissioned report by a UK-based human rights lawyer, sent in January 2018 to Director General Marco Lambertini and Chief Operating Officer Dominic O’Neill, documented “accelerating” accounts of violence by WWF-backed guards in the forests of southeast Cameroon.

The document, obtained by BuzzFeed News, outlined “very serious and widespread” allegations that forest rangers employed by the country’s autocratic government had abused local residents, often “in connivance with and under the watchful eyes of WWF staff.” Its author concluded that villagers’ accusations were not just “valid” but “grossly understated."

The report, by Paul Chiy of De Jure Chambers, is the first concrete evidence that WWF’s leadership in Switzerland had been warned about atrocities by anti-poaching rangers before abuses were uncovered in March.

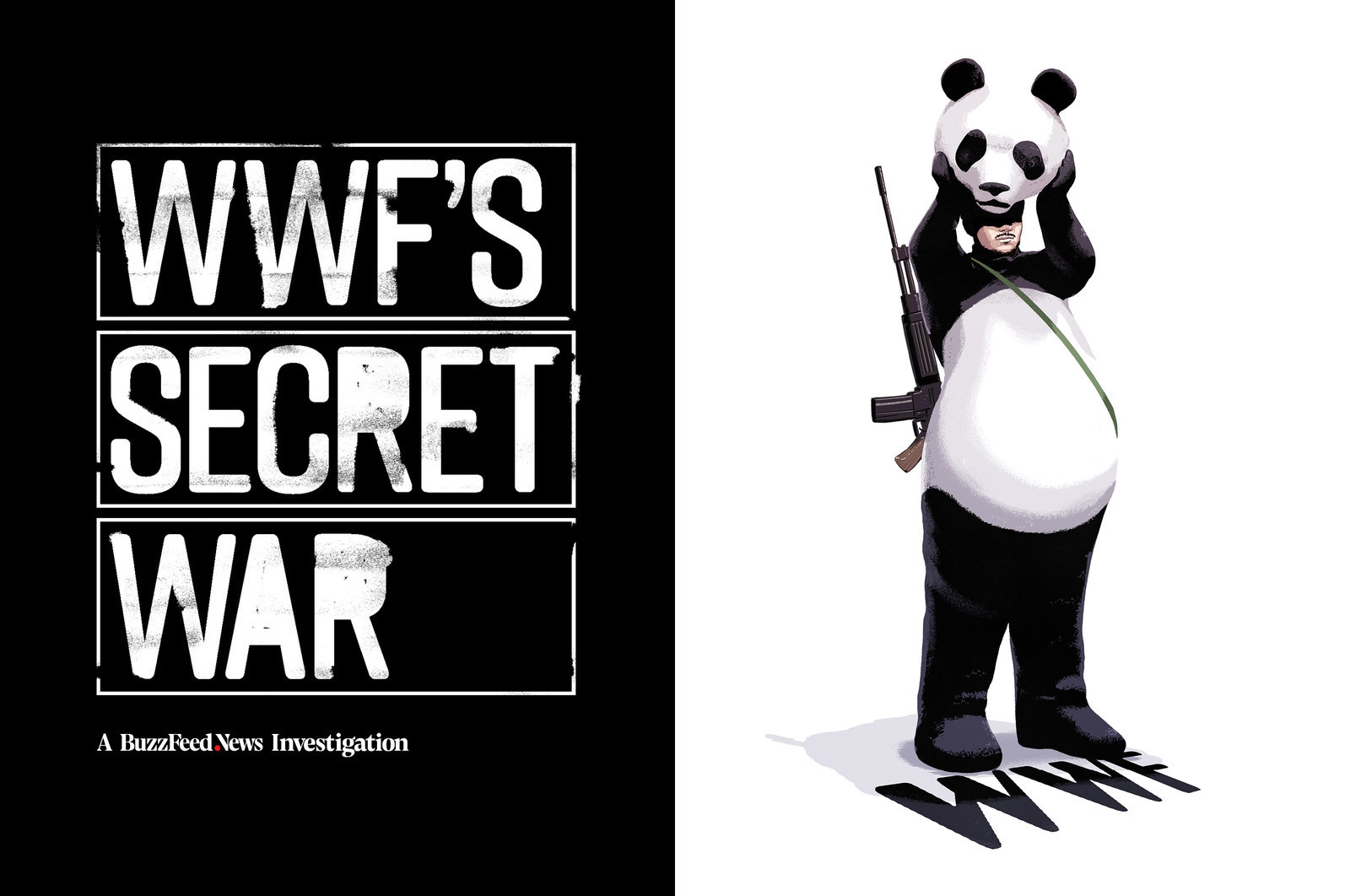

That’s when a BuzzFeed News investigation revealed that the global mega-charity with the cuddly panda logo supports forces that have been accused of beating, torturing, sexually assaulting, and murdering people living near wildlife parks across Africa and Asia. In response, the US, Germany, and the UK — all of which are WWF donors — launched investigations to ensure taxpayers aren’t funding abuses, and the charity commissioned an independent review led by the former United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

WWF has downplayed the allegations, claiming that BuzzFeed News' reporting does “not match our understanding of events.”

But when asked about the contents of the Chiy report, WWF acknowledged that the charity was “well aware” of the “challenges” it faces in Cameroon.

The report was "discussed with the leadership including with the Director-General, Marco Lambertini, and the International Board, and they discussed and noted a timeline of actions up to the end of 2019,” WWF said in a letter from law firm Carter-Ruck. “This work is ongoing,” the firm added, and there is "no doubt that the Chiy report has been acted upon." WWF does not publicly release such documents out of fear for “the health and safety of the witnesses cited” and “in order not to interfere with due process,” it said in a statement.

Chiy declined to comment. His dossier is one of at least four internal reports commissioned by WWF since 2015 to warn that the charity risked complicity in abuses against indigenous people — and the second to raise serious alarm about violence in southeast Cameroon. WWF kept all of those reports under wraps until BuzzFeed News exposed them, while continuing to fund the areas in question. Chiy’s report is the first that can be traced all the way up to the charity’s director and board.

Chiy’s findings were devastating. Anti-poaching forces had reportedly raped a woman, tortured a man by tying his penis to “pulleys,” and forced one villager to eat raw bush meat, after which he became ill and died, the lawyer reported. The problem was widespread — four out of five interviewees had reported “nightmare encounters,” Chiy wrote.

The charity needed to take “immediate and urgent” action to protect indigenous people, and the report laid out a step-by-step plan for how WWF could clamp down on the violence. It should support legal action against Cameroon through the United Nations and the African Commission, Chiy wrote, and revise its complaints system for victims to report abuses. He envisioned a massive media outreach campaign, led by WWF executives, to raise awareness of the plight of indigenous people “who feel totally voiceless and powerless.”

A year later, O’Neill told BuzzFeed News in an interview that human rights abuses were a “red line” the charity would never cross. Lambertini declined to be interviewed.

“No human rights abuses at all are acceptable to us,” O’Neill said. “If the wrong thing is happening, then we want to act. It’s in our ethics to act immediately.” He didn’t mention Chiy’s report. Nor did he acknowledge that WWF had failed to act on some of those key recommendations, according to internal records. Some “issues” had cropped up in Cameroon, O’Neill said, but WWF had “dealt with” them.

In its statement, WWF provided BuzzFeed News with a lengthy list of steps the charity has undertaken in Cameroon, including a trip O’Neill took there to advocate for “clearer government accountability on human rights and community welfare matters.” WWF is negotiating a new agreement with Cameroon to ensure “appropriate government oversight of eco-guards under its command.”

When asked why the charity's leadership did not embark on the transparent outreach initiative Chiy suggested, a spokesperson said “positive and lasting impact” is “unlikely to be achieved solely through a mass media campaign.”

Cameroon’s park rangers, known locally as “eco-guards,” police the country’s national parks to protect endangered species such as forest elephants and lowland gorillas from poachers. When the government created the parks, indigenous people lost access to wide swaths of forests where their ancestors had for generations gathered food, built shelter, and made medicine out of natural resources.

They also began reporting abuses by eco-guards, who have patrolled alongside the Battalion d’Intervention Rapide (BIR), a special forces unit that has separately been accused of killing unarmed civilians. The guards are employed by the country’s longtime leader Paul Biya, but WWF, which has worked in Cameroon since the 1990s, has long provided them with critical training and supplies.

In 2003 an activist wrote directly to Prince Philip, one of WWF’s original cofounders, warning that he was “extremely concerned about the activities of the WWF” in the region and arguing that the charity was “actively destroying” the local indigenous culture. Phillip sent his letter to the head of WWF-International, who vowed to investigate. The charity did not respond to a question about whether it followed up.

Make more work like this possible: become a BuzzFeed News member today.

Over the next decade, WWF received various complaints from other NGOs claiming that eco-guards were terrorizing indigenous people in Cameroon. In 2015, the charity commissioned an internal report on the region, obtained by BuzzFeed News, which found that locals were “victims of human rights abuses and violations” by eco-guards and that perpetrators were backed by “considerable technical, logistical and financial support” from WWF. It recommended that the charity overhaul its complaint system for villagers to report allegations, and “establish harsh consequences” for eco-guards who broke the law.

But the charity kept funding the guards, and the problem did not go away. In 2017 a complaint submitted to the UN accused WWF of supporting Cameroonian guards who deployed “intimidation, brutality, torture and arbitrary punishment.”

Publicly, WWF continued to proudly showcase its relationship with indigenous communities. “Working with people is at the heart of everything we do,” WWF Cameroon’s website says alongside photos of colorfully dressed locals with captions such as "Indigenous People are very hospitable. Offering gifts to guests is their passion.”

But behind the scenes, O’Neill, who joined WWF International in 2017, commissioned Chiy to look into the situation further. Chiy, who also practices law in Cameroon, reviewed thousands of pages of documents and spoke with local NGOs. He requested financial records from WWF to track how the charity funded the eco-guards, but never received them, he wrote in his report.

In the field, his team had just under a week to conduct interviews with alleged victims. They traveled for hours over the precariously potholed roads that lead to Boumba Bek, Nki, and Lobéké national parks to speak with the villagers who live on the outskirts.

One man said he had been tortured and forced to sleep in a cell filled with water to chest level for four days, because rangers thought it was suspicious that he was able to afford a new motorbike. Soldiers working with the rangers took him to an abandoned quarry. There, they tied a cord to his penis and passed it through a pulley, “and each time they asked him a question and he did not say what they wanted to hear, they pulled the cord and it stretched his manhood,” the report said.

A farmer said that his family had been tortured repeatedly, his wife raped, and he and his father imprisoned — all on the basis of false poaching accusations. “He says he took his wife to the hospital where he spent a lot of money but that to date his wife still has medical problems as a result of that assault,” the report said. He wanted to file a lawsuit, but “did not have the means to bring a case against a law enforcement officer,” so he abandoned it.

A teacher said that he witnessed eco-guards force a young man reselling bush meat in town — a regulated trade WWF acknowledges is "critical to the livelihood of the rural poor" — to eat a raw chunk of his wares. The man became seriously ill and later died.

Eco-guards, whom villagers described as “crude and poorly trained” or “extremely corrupt” and “often disgruntled,” often didn’t have clear evidence that the people they were targeting were poachers, the report said. WWF says it wants indigenous communities to have access to the forests and does not see them as its target — its goal is to take down organized criminal gangs, not villagers struggling to make a living. Yet one man told Chiy’s team that guards “do not bother to verify information before acting on it and when they do, they do so violently and indiscriminately (beating up everyone around until they bleed).”

Victims were willing to help identify abusive eco-guards, Chiy wrote, but they felt they wouldn’t be treated fairly by law enforcement. “In almost all the cases recorded, interviewees decried the absence of due process,” he wrote. “They feel so helpless in the light of the fact that they are being oppressed by the same people they had hoped to run to in the time of trouble.”

Chiy expressed alarm at how deep complaints ran. “Beyond confirming specific allegations of abuse, every four out of five interviewees had their own stories to tell” of “their own nightmare encounters,” Chiy wrote.

Chiy acknowledged that WWF did deserve praise for its “novel approaches to conservation management,” such as its efforts to limit “commercial exploitation,” and for lobbying the Cameroonian government to pass laws protecting indigenous people’s rights.

On paper, Chiy wrote, WWF’s strategy was “widely recognized as a good model for balance between conservation and other needs of forest users.” But he warned that the charity’s “limited” efforts to turn their policies into reality were “piecemeal, uncoordinated and did not empower” locals “to take the lead.”

WWF had “avoided” developing a working system for “responding to incidents and dealing with allegations” and its resources for victims did not “properly consider the realities on the ground,” Chiy wrote. Instead, it seemed to be “targeting a literate audience with telephone and Internet access” when many locals “cannot write, many do not have phones, and many live in locations where there are no telephone networks,” he wrote.

Chiy submitted a list of recommendations, many of which were marked “urgent” and “immediate.”

WWF needed to take a much tougher stance toward Cameroon’s autocratic government, Chiy wrote. If WWF didn’t explicitly come out against the regime’s violence, then the charity was liable to be “named” as a perpetrator alongside the government. This, he said, was WWF’s “greatest risk.”

WWF had promoted “no shortage of workshops, trainings, meetings, reports, strategies, media reports, press releases, plans, discussions, lessons-learned … and even laws,” Chiy wrote. Yet those endless discussions “have not resolved most of the issues” encountered by indigenous people for decades, Chiy wrote. “Rather, the growth and expression” of these issues — “particularly allegations of human right abuses” — have “accelerated.”

Chiy still held faith in WWF’s future — as long as it responded aggressively.

WWF's top leadership could go on TV, pen op-eds and organize international conferences, Chiy wrote. WWF could use its website and social media to teach its millions of donors around the world about the hardships indigenous people face.

“WWF must raise awareness of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and highlight its commitment to them,” he wrote.

Chiy wrote three reports for WWF. Another was also about a troubled region where eco-guards have been accused of human rights abuses, and the third analyzed the deaths of 11 rhinos in Kenya after a disastrous attempt to move them to a new sanctuary.

WWF issued multiple press releases about the rhino deaths and touted the report’s key findings about how WWF could help prevent similar mistakes in the future.

Yet WWF has never publicly acknowledged Chiy’s other investigations.

In January 2019, O’Neill sat down for an interview with BuzzFeed News at WWF’s international headquarters in a quiet suburb of Geneva. Reporters had contacted him in the midst of a yearlong investigation into abuse allegations at a half dozen countries where WWF partners with local forces. By now, O’Neill had reviewed both the 2015 and 2018 reports on WWF’s parks in southeast Cameroon. And WWF had received a separate review, obtained by BuzzFeed News, about a park in the Republic of Congo where villagers voiced concerns about eco-guard “repression.” None of the reports had caused WWF to stop supporting the areas in question. The charity was also aware of similar allegations at three other WWF-funded reserves in two other African countries, according to records reviewed by BuzzFeed News.

O’Neill did not provide details of any of those internal reviews. But he spoke at length about WWF’s zero-tolerance policies and insisted to BuzzFeed News that eco-guard violence was not an epidemic. “We’re talking a relatively small number of cases, in certain pockets,” O’Neill said. He pointed out that problems usually come up in “fragile states,” such as in the Democratic Republic of Congo. But he said that if WWF ever felt a government partner wasn’t addressing human rights abuses properly, the charity would stop working with them. “We wouldn’t hesitate,” he said.

In March, BuzzFeed News published its findings, triggering WWF’s independent review, which it says it will make public, and a wave of investigations by government agencies in the US and Europe.

Got a tip? You can email tips@buzzfeed.com. To learn how to reach us securely, go to tips.buzzfeed.com.

Around that time, WWF received another internal report it had commissioned, about Salonga National Park in the DRC. It found evidence of torture and the gang rape of pregnant women at the park, which WWF comanages. Yet once again, WWF kept the report under wraps. Documents seen by BuzzFeed News show WWF asked the park’s German government funders to treat all details of the investigation and its findings in a “non-public fashion.” BuzzFeed News obtained the report in July. WWF said in a statement that all the rangers implicated in the abuses had been suspended on the charity’s recommendation, and it chose not to publicly release the report because of concerns over victim confidentiality and due process.

WWF did make some changes in Cameroon following Chiy’s report. A spokesperson said the charity had taken “more than twenty actions” on the ground in Cameroon as a result of its reviews. The charity stopped using WWF-branded cars to transport eco-guards, for example, and launched a new five-year strategic plan to promote indigenous rights and local resource management. O’Neill also traveled to Cameroon to meet with the government’s head of wildlife to advocate for clearer government accountability. After O’Neill’s interview with BuzzFeed News, the government and local communities signed a new agreement that gave indigenous people more access to the forest.

But WWF sat on a number of Chiy’s other recommendations for more than a year. Only after the US government began asking questions did WWF enact sweeping new "safeguard" policies that address the safety of indigenous communities in all the areas where the charity operates. Chiy wrote that WWF “must immediately” dig further into a WWF staff member’s admission that “there have been some verified instances of abuses” in Cameroon. Records show that the charity only now plans to address the issue in its upcoming independent review.

WWF still hasn’t finished its new system for victims to make complaints. It never supported legal action against the Cameroonian government through the UN and the African Commission. Chiy had retained Cameroonian lawyers to help WWF assist victims, for free — but WWF never took him up on the offer.

The independent review into WWF, led by former UN human rights commissioner Navi Pillay, is still ongoing.

But the villagers who live near WWF’s parks in southeast Cameroon have lost faith, said Charles Jones Nsonkali, a Cameroonian indigenous rights activist.

“The Baka know if they go into the forest they will be beaten again,” he said. “They don’t trust WWF.” ●