In January of 1998, CNET reporter Janet Kornblum looked back on the internet's big year:

In 1997 [netizens] found that there were any number of places--from traditional search engines such as Yahoo and Excite to software companies, online services such as America Online and Microsoft Network, and start-ups--that delivered, or at least promised to deliver.

Web sites reorganized and launched, trying to morph themselves into that perfect site--the one so well-organized, so fast, and so filled with information that surfers need go nowhere else.

In 1996, the distinction between search engines, online services, and free centralized sites was fairly clear. In 1997, the lines began to blur and have grown increasingly fuzzy. By the end of 1998, with so many companies adopting similar interfaces and strategies, there might not be any discernible distinctions among different kinds of sites.

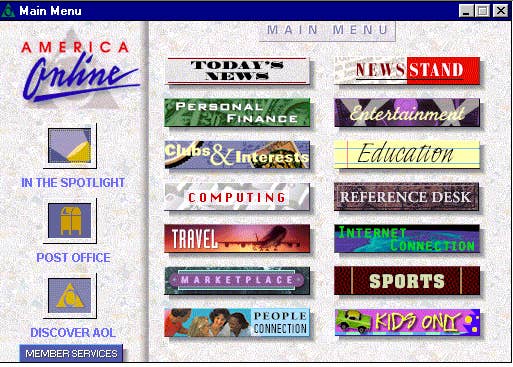

1997, in more modern language, was the year that every site became a portal. At the time, these portals, or channels, were built around search engines, email providers and internet service providers. If you got your internet through AOL, you probably used AOL's email service and homepage. The internet was much smaller than it is today but so poorly indexed that it felt unknowably massive. It needed tour guides and starting points, and portals were there to help.

Portals were also basically attentional cash-ins — they were less about attracting new audiences than taking advantage of captive ones. At its peak, AOL had 30 million subscribers, most of whom landed at AOL's homepage every time they logged in. It was an unintentional void, so AOL filled it the only way anyone knew how: with headlines divided into categories.

Now, in January of 2014, one could write a similar story about the internet's largest companies and their approach to news. "In 2012, the distinction between social networks, news sites, and and online communities was fairly clear," you could claim, accurately. "In 2013, the lines began to blur and have grown increasingly fuzzy. By the end of 2014, with so many companies adopting similar interfaces and strategies, there might not be any discernible distinctions among different kinds of sites."

In 1998, it wasn't yet clear that social networks would supplant search and portals. And in early 2014, it's too soon to say with any certainty what comes after Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn. All are betting on mobile, but it's not clear exactly what that means, or which of them, if any, will win.

But lines are certainly blurring, and distinctions in their core products — their feeds — are vanishing. On Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook, users post units of content that can be liked, favorited or commented upon. The functional differences between these sites lie in who can see the units and how they can be re-shared. The practical differences between these sites depend mostly on which of your friends use them.

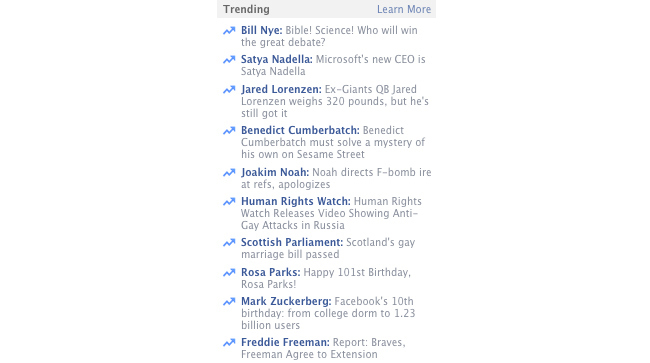

Like portals in 1997, the feeds are growing but established — they're here to stay, at least for a while. But these companies now largely know what they're working with, and their starting to act like their ancestors. Facebook, in particular, is marking its tenth anniversary by openly embracing portalhood, at least for news. On the desktop, that means introducing trending topics:

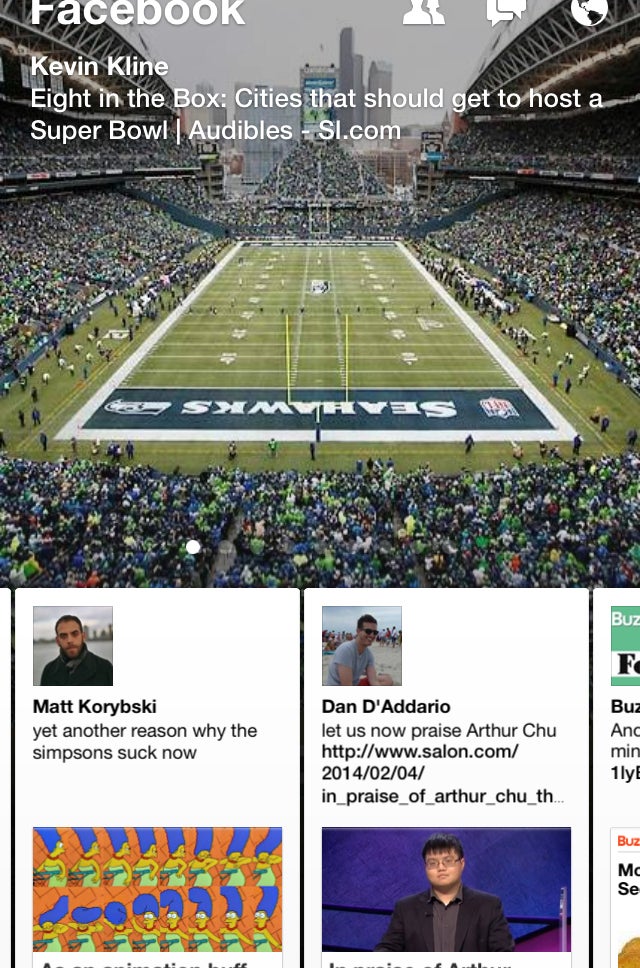

On mobile, the change is represented by Paper, Facebook's new app. It's a near-total replacement for the basic Facebook app experience, but instead of focusing on Facebook's many moving parts, it's focused on reading. It defaults to your main feed, of course, because that's why you're on Facebook, but surrounds it with curated news feeds:

It's a strategy right out of the portal playbook. From the same CNET piece:

The message on the Web has always been, "It's the content, stupid." And in 1997, as the Net gained a hold in mainstream America, it became clear that Netizens not only want great content, but they generally want it to be free, well-organized, accessible, and packed with useful, reliable information.

Contrast that with Facebook's Paper announcement:

Your Paper is made of stories and themed sections, so you can follow your favorite interests. The first section in Paper is your Facebook News Feed, where you'll enjoy inspiring new designs for photos, videos, and longer written posts. You can customize Paper with a choice of more than a dozen other sections about various themes and topics—from photography and sports to food, science and design. Each section includes a rich mix of content from emerging voices and well-known publications.

Twitter, let it be said, is assuming portal-like qualities as well. In a recent update to its mobile app, it has started supplementing users' main feed with inline recommendations. A swipe to the right now reveals a Discover tab.

Both changes suggest — the former, explicitly — that Twitter knows it has your attention, and it trying squeeze everything it can out of it.

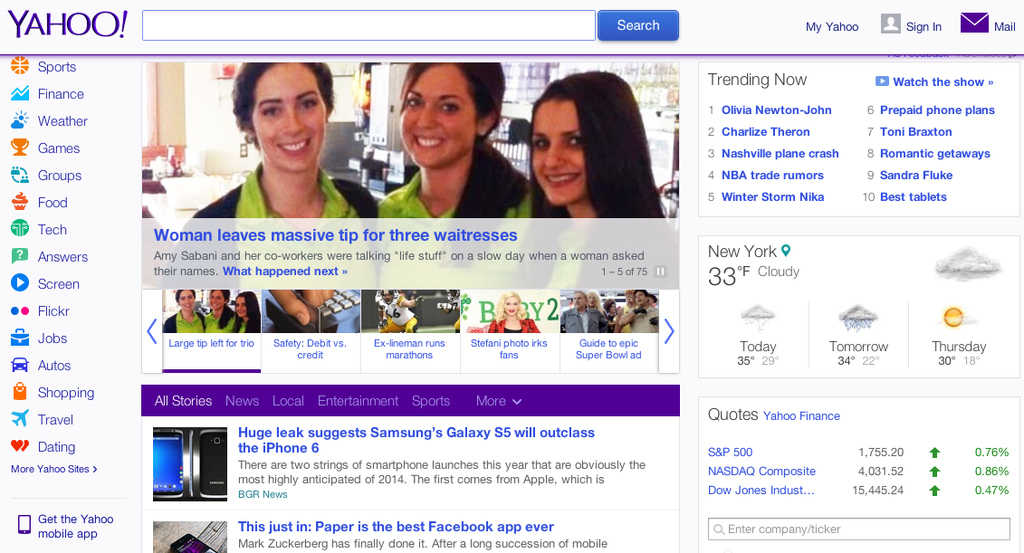

Many of the old portals still exist in one form or another, but none are as well preserved as Yahoo. As far as regular people are concerned, Yahoo's homepage, search and mail products still define the company (Investors would that the company is defined by its massively successful investment in Chinese e-commerce site Alibaba).

Looking at Yahoo's or AOL's homepage now is instructive. Paper is strikingly similar right down to the one-word category names. AOL's "Newsstand," "Marketplace," and "Entertainment" have been replaced by "Headlines," "Enterprise," and "LOL."

Facebook's Paper app is beautiful, but without the presence of the user's primary feed, its story mix — its sensibility, if you can call it that — is similar to every other general interest front page's.

Twitter's additions to the main feed seem to be at first glance more timely; breaking news shows up while it's breaking, albeit stripped of all the personality that vivifies Twitter in the first place. An illuminating tweet from a reporter who broke the story, retweeted hundreds of times, is portalized into "Senate Passes Farm Bill." Facebook's trending topics are similarly lifeless — it's honestly the first thing you notice about them.

There is an obvious and strong case for presenting the news of the day in plain language and an orderly fashion. There's a similarly strong case for adding weather updates and stock prices. But is it Facebook's job to do it? Does anyone really love these second-tier additions? Do you, or anyone you know, have truly fond memories of any 90s web portal? Or were they just there? For news, portalization is a fate not quite worse than death.

This is the behavior of companies that are figuring out what comes next. For Facebook and Twitter, the tentative and vague answer is "mobile" — all ways, all kinds. For the portals, it was social media.

Well, eventually: First there was the crash.