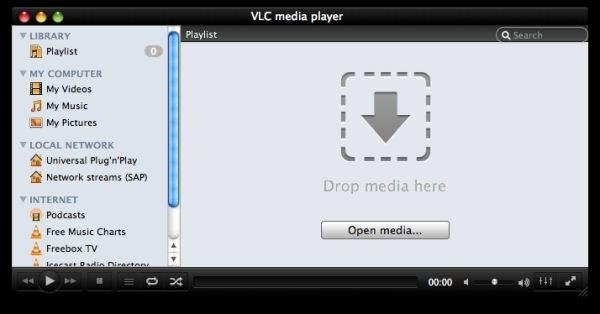

VLC is not like most super-successful software. It's made by a small group of effectively anonymous volunteers rather than a massive tech conglomerate. Its logo is a traffic cone, a pointedly obscure reference to a prank pulled by a group of French college students about 10 years ago, before they helped create the app. (VLC applies this seemingly inexplicable icon to users' video files, meaning it's been reproduced countless billions of times.) Its original name was the less-than-descriptive "VideoLAN Client," and its main interface and menu system is still unapologetically raw and unsoftened, festooned with video jargon and features that most people will never touch. It's free.

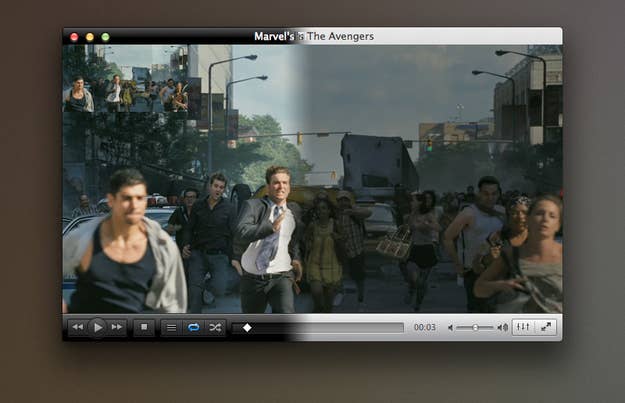

Appearances aside, VLC's purpose — and value — is abundantly and immediately clear: It plays video. Any video. It plays all the videos that QuickTime and Windows Media Player can play as well as ones they can't. It plays videos from virtually any camera. It plays videos from any website. It plays videos from any file-sharing service. It'll even attempt to play partially downloaded videos, and occasionally succeed. It plays all these videos immediately and without fuss. That traffic cone is magic.

Playing videos on a computer hasn't been novel for about 20 years, but playing the videos you want is still oddly difficult in 2012. The video players included with Windows and Mac OS play a sharply limited number of video formats due to crippling licensing restrictions — to include the ability to play or create videos in, say, h.264 format, Microsoft and Apple have to pay royalties to the people who hold the patents on its codec technology. This has created a somewhat embarrassing gap in the capabilities of the two major operating systems: out of the box, Windows 7 and Mac OS X Lion can't play some of the most popular video codecs in the world. (The next version of Windows, due later this year, won't even support DVD playback. Luckily, VLC does that too.)

VLC's success is, in a way, a powerful expression of the strangeness of software patents. The app uses open-source video playback and encoding libraries, which may well be in violation of quite a few software patents, but their volunteer creators profess (likely feigned) ignorance on the subject and can point to years of undisturbed operation as evidence that it doesn't really matter — as long as you don't charge for your software. VLC's legal status is best described, I think, as fine enough.

This ability to do for free what the world's most popular paid operating systems apparently can't has made VLC a mandatory download. It's the first thing I put on a new computer after Chrome or Firefox, and my DVD player of choice and go-to app for playing torrented files. I've come to depend on a few of its less obvious features, of which it has hundreds, and regularly use it to slow down audio files (oh, it plays music, too) for transcription or to crank up the volume on a too-quiet DVD rip (VLC's volume knob goes to 11 — or more accurately, 200%). I've come to think of VLC as something more essential than an app — it's more like a must-have patch for Windows, Mac OS and Linux. Digital video is broken is a grand way, and VLC has been dutifully fixing it for years.

A billion downloads in, though, I'm starting to see the first signs that VLC's peak may be nearing. I open it far less than I used to, in part because I'm streaming more legitimate content from the internet and in larger part because a lot of the large private torrent sites — TVTorrents and EZTV — have started requiring users to upload videos in h.264 format, which works with most video playing software and, crucially, on mobile devices, game consoles and TV streaming boxes.

VLC hasn't really made the jump to mobile, and it likely never will. It was in the App Store for a short time before getting pulled over a stubborn open-source licensing issue; since then, a handful of similar multi-format video players have appeared to take its place. And in any case, the world of mobile is one where video formats just don't seem that important. Video on mobile usually streams though a browser, inside apps, or from a store. iOS doesn't have file extensions or even a file system, and you rarely find yourself tapping on a video and getting a "file format not supported" error message. VLC is the quintessential desktop utility, a type of app that doesn't fully translate to mobile.

That said, of those billion downloads over the last seven years I probably account for at least a hundred, and will end up accounting for a hundred more. And I don't care how rarely I end up using it: I'll give you my traffic cone when you pry it from my cold, dead hands.