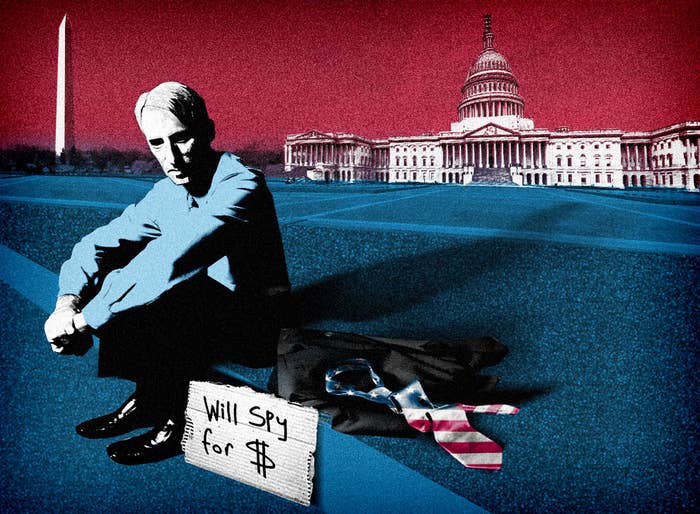

WASHINGTON — The mandatory cuts to federal spending threaten to become an unexpected security nightmare for the federal counterintelligence agencies that protect government institutions against foreign spying.

Lawmakers and officials who oversee security clearances say the abrupt cut to roughly 20% of federal workers' pay is pushing tens of thousands into the category of financially strapped government workers for whom foreign agents look in recruiting moles and spies.

It may sound far-fetched, but those with experience in espionage cases said the threat is genuine.

The risk that financial hardship could lead to espionage is "definitely a concern," South Carolina Senator Lindsey Graham, a former Judge Advocate General in the Air Force, told BuzzFeed.

"When I was in the Air Force we had a few espionage cases. Every time we had an espionage case, it was somebody who got involved because their life had fallen apart," Graham said.

Lawmakers and sources working in the security clearance process agreed the sequester's cuts could give outside forces — ranging from allies like Israel to rivals like Russia and China — a fresh crop of potential recruits.

"It's expanding the number of people for them to target," one official involved in the security clearance process warned.

America's classified national security apparatus, in the public and private sectors alike, has been booming since Sept. 11, 2001, and 4.8 million U.S. citizens currently hold a security clearance, according to an October 2011 survey by the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the first and only survey of security clearances. There's even a booming business of matching cleared workers with open jobs that require a clearance, one that offers people like Evan Lesser, the founder of the Des Moines–based ClearanceJobs.com, a glimpse into the sprawling world of jobs that require keeping secrets.

"If workers with security clearances are furloughed … you're going to see a lot more people with security clearances in financial difficulties, and that will have a negative impact on national security," said Lesser, a former manager at federal defense contractors.

The vast majority of clearances are for the lowest classification, known as "confidential," which grants the holder access to sensitive information or so-called "clean" facilities that are highly secure.

According to Lesser, while some of the clearances are for jobs like spies, intelligence analysts, or senior officials, most "[are] IT, engineering, logistical, and management roles."

"You can have truck drivers with security clearances. The people who cook meals on … Air Force One have security clearances," Lesser said.

From a security standpoint, that means that there are millions of Americans with knowledge of what may seem like mundane information — say, the time a truck driver is to report for duty on a particular day — but which could be critical to agents looking to hijack sensitive chemicals, attack an installation, or simply track movements of government officials.

Pop culture depictions of espionage often focus on the sexiest of spying tactics: high-tech snooping, or "honey traps" baited with kinky sex, and targeting White House officials. But while those sorts of tactics certainly play a role in modern espionage, the vast majority of the craft is far more mundane, consisting of tedious hours of identifying workers with financial difficulties who can be subtly exploited and then slowly cultivated over time.

And intelligence community sources said there are several areas that screeners look for when determining whether an applicant for a security clearance should be approved. For instance, there are obvious red flags, like direct involvement in subversive or terrorist organizations; personal secrets; or failing lie detector tests.

But those issues either keep vulnerable people from applying for jobs in the first place or quickly rule them out for security clearances early in the review process.

And the intelligence officials said the biggest concern investigators have is financial in nature. People with massive debts, loans, or gambling obligations are extremely vulnerable to recruitment by foreign agents, since they can offer a quick and seemingly easy way to maintain their lifestyle.

"Delinquent debt is what we look for," one source involved in clearances explained.

Lesser agreed, explaining, "One of the primary reasons a person can be denied a security clearance is because of financial concerns."

But while the front-end security clearance process can weed out anyone in that position when they first apply, the sequester has placed a new and potentially dangerous pressure on federal workers.

A significant number of federal workers, contractors, and military personnel who have been cleared for secret or top-secret clearances are either living paycheck-to-paycheck or close to it. With the sequester resulting in furloughs that are cutting more than 20% of their pay, many of those people will suddenly find themselves in a financial bind.

In fact, like most Americans, people with security clearances have already started to feel the pinch.

"As we've seen over the last number of years with the recession, it's been harder and harder for people to keep their clearance because of what has happened in the economy," said Lesser.

Most will respond by finding ways to cut their expenses. Others will simply acknowledge their difficulties and file for bankruptcy, which will not necessarily cost them their clearances.

But for others, the social stigma of bankruptcy and the social and familial pressure to maintain their lifestyles could become too much — making them perfect targets for foreign agents.

One of the key problems is that once an individual has security clearance, that person has years to operate unmonitored by authorities before his or her next review. Depending on the level of clearance, these periodic "reinvestigations" occur anywhere from five to fifteen years after the clearance was issued. Although there is a "self-reporting" rule that requires clearance holders to inform investigators if they go into bankruptcy, are going through a divorce, are in therapy for certain types of mental illness, and other red-flag issues, it's a voluntary system.

"No, nobody's monitoring them," said Lesser.

Michael O'Hanlon, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, acknowledged that the sequester could push government workers and military personnel into becoming agents for foreign governments, but argued that most are already willing to sell out their country like Jonathan Pollard, a civilian intelligence officer who spied for the Israeli government.

"It's hard to rule out that kind of person existing," O'Hanlon said. "On the other hand, wouldn't that be shameful … their behavior would be every bit as criminal as Jonathan Pollard."

But not all, or even most, people who end up spying on their own country are motivated by ideological reasons.

Robert Hanssen is a former FBI agent who spent more than two decades working for Soviet and Russian spymasters. Hanssen, a devout Catholic and ardent conservative, was not turned for ideological reasons. But with seven children and a stripper-cum-mistress to support, Hanssen simply needed cash. Over his 22 years as a spy, Hanssen collected more than $1.2 million in cash and diamonds from his handlers in exchange for information.

With the sequester cutting workers' pay, stories like Hanssen's could become more common, and ironically, will put further stress on a sprawling security system that is itself facing new strains from the sequester.

"Stability is a good thing," Graham said. "That's why you monitor family problems, alcohol problems."