The wolverine looks like a monster.

Built like a bear but actually the largest member of the weasel family, the animal has evolved to survive in brutally high altitude, high latitude environments. Its large, clawed paws — which inspired the Wolverine — act like snowshoes and let it move with astonishing speed over rugged terrain. It's comfortable at -40 degrees F. Its jaws can snap a moose bone. It gives birth in a snow cave.

But recently the wolverine has displayed yet another remarkable ability: becoming the spark in a legal fight that’s roiling the West and catapulting climate change to the front lines in the battle over public land.

That final feat reached a climax this month when a judge ruled that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had erred when it suddenly reversed course in 2014 and decided against designating the animal as an endangered species due to threats posed by climate change. Other animals — such as the polar bear and a subspecies of the red knot — have been listed due to climate change threats, but the wolverine would have been far and away the most significant listing in the American West.

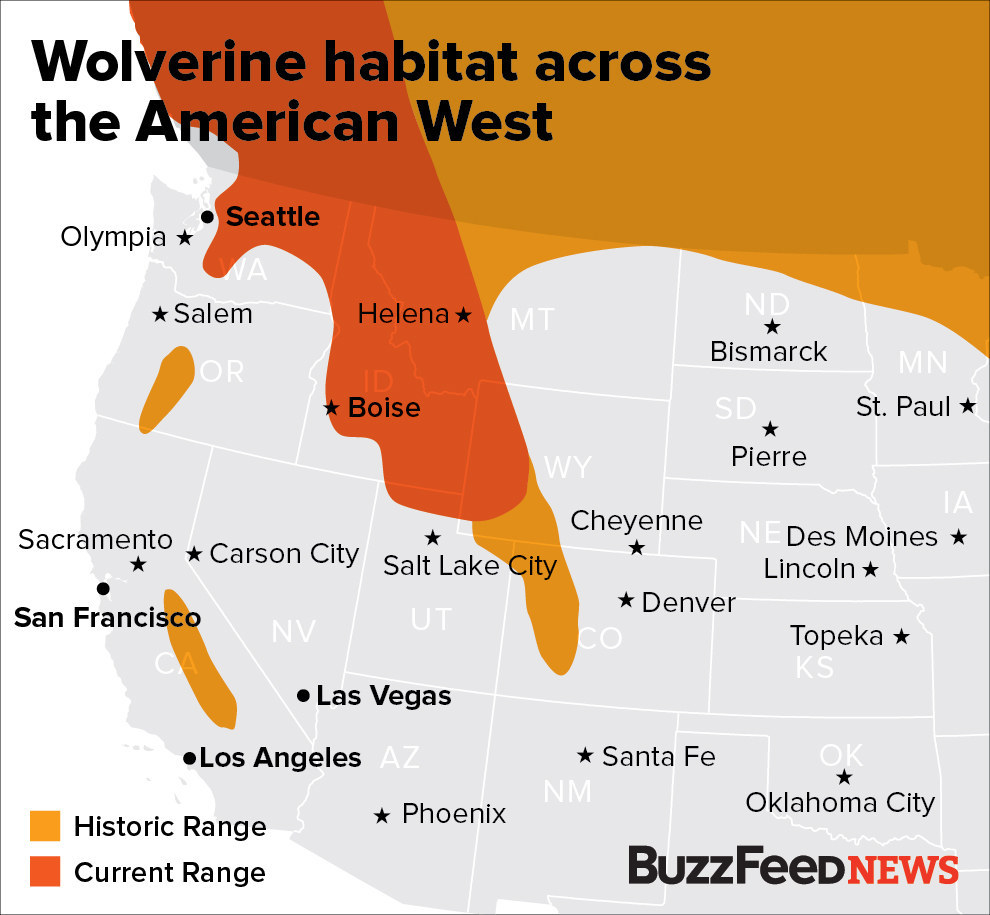

Environmentalists argue warming temperatures in North America will reduce wolverine habitat by shrinking the amount of available snowcover. Wolverines give birth in snow dens, and rising temperatures coupled with precipitation falling in the form of rain, instead of snow, could mean fewer kits in the future. And those conditions could threaten the animal across it's range.

Gavin Shire, a spokesman with the Fish and Wildlife Service, told BuzzFeed News the agency reviewed the science on the impact of climate change and concluded "that the wolverine was in fact not threatened with extinction in the foreseeable future." And so the agency withdrew its proposal to list the animal.

"There is a very clear correlation between the rising temperatures and decreased snowpack," Shire said. "What is not as clear is the impact of that declining snowpack on the wolverine."

Shire also said wolverines actually appear to the expanding their U.S. range — which is the opposite of what might be expected from a species facing extinction.

"There have been wolverines that have been sighted in areas where they haven’t been found in quite some time," he added.

Still, in response, a coalition of environmental groups sued, arguing that there are only 300 wolverines remaining in the contiguous U.S. and that they are "threatened by climate change and other human disturbances." The groups argue the status of the current wolverine population — even if it's expanding, as Shire said — will face an existential threat in the future due to the effects of climate change.

"In this case all the evidence and the records and the peer reviewed papers suggested there was a problem, a threat, and there was no scientific paper saying otherwise," Matt Bishop, an attorney with the Western Environmental Law Center who worked on the case, told BuzzFeed News.

Another coalition made up of Western states, farmers, ranchers, snowmobile groups, and oil industry representatives joined the lawsuit in support of the decision not to list the wolverine. Ethan Blevins, an attorney with the Pacific Legal Foundation who represented some of those groups, said the science on climate-based threats to the wolverine "was pretty speculative," adding that the Fish and Wildlife Service was free to say "we don't think the science is good enough yet."

A federal court disagreed. In a ruling earlier this month, Chief Judge Dana Christensen of the United States District Court for Montana slammed the Fish and Wildlife Service, calling the decision to withdraw the endangered species proposal "arbitrary and capricious."

Bishop said that a key part of the ruling boils down to the idea of the "best available science." Though climate predictions aren't exact and wolverines are difficult to study, the judge decided there doesn't need to be incontrovertible proof of an imminent threat in order to list the wolverine. Instead, officials are free to act based on the best information that's available to them.

"Biologists said, 'we’re never going to get a smoking gun with wolverines,'" Bishop said. "But the conclusion was that we don’t need to know before we list. [Wolverines] are going to lose a lot of habitat."

What happens next is still up in the air. The Fish and Wildlife Service could decide to appeal the case or, more significantly, put the wolverine back on the list of potentially endangered species and reconsider the threats it faces.

That decision could mark a dramatic new chapter in a long-running battle over the federal government's control of huge swaths of Western land and wildlife protections. The 2014 and 2016 Bundy standoffs in Nevada and Oregon; an ongoing fight over a national monument in Utah; anxiety about an endangered species listing in New Mexico; and several other smaller skirmishes are just some of the recent flashpoints.

The conflict goes back to the frontier days but was reignited in the modern era with the signing of the Endangered Species Act in 1973 — just a few years before angst in the West boiled over into a loose movement known as the Sagebrush Rebellion. Over the ensuing decades, the act would become a complex legal and strategic device in the struggle that often pitted conservationists against ranchers, loggers, and oil and mining interests.

In the late 1980s, conservationists fighting to curtail the number of trees being cut down on public lands in the West successfully lobbied the federal government to designate the northern spotted owl as a threatened species, scoring a major victory against the logging industry. As news reports suggested at the time, the listing was a kind of coup de grâce for conservationists in the long running battle.

For the next few years, conflicts over logging continued to bubble up into the public consciousness, leading to everything from so-called "timber wars" to curious pop culture references like an episode of X-Files in which Mulder and Scully fend off deadly bugs against the backdrop of Washington logging tensions.

In recent years, however, references to logging issues — either in news reports or pop culture — have all but disappeared. That’s due in no small part to the broad effect of the spotted owl designation, according to dozens of people across the West who have spoken with BuzzFeed News for this story and others. The listing, they say, lead to a gradual decline in logging in the region, and in some areas a complete halt.

"There used to be a lot of mills. Now there's just a few big ones left."

"There used to be a lot of mills," John Thompson, spokesman for the Idaho Farm Bureau told BuzzFeed News. "Now there's just a few big ones left. A lot of it was the spotted owl."

The designation marked a turning point in the battle over land in the West and is one that continues to resonate; call up local officials or ranchers in the West and it's only a matter of time before the spotted owl comes up.

In the years after the spotted owl listing, scores of species were listed as endangered or threatened, and many of those protections intensified friction between the conservationists who saw them as important victories and those in the agricultural and mineral industries.

A potential listing of the wolverine due to the threat of climate change could be a watershed moment for environmental groups that opens the door to new protections but also pours gasoline on the embers of smoldering western land conflicts.

In recent years a growing body of legal and environmental literature has linked climate change to what some theorize could be a strengthened Endangered Species Act. One paper, which discusses the polar bear listing, explicitly notes "the strength of the Act" and suggests it "may be a new avenue for climate change litigation."

The potential danger posed by climate change is also being floated in a number of other cases, including in the Arctic, where the Pacific walrus is currently a candidate for designation as a threatened or endangered species. According to the Fish and Wildlife Service, "the walrus population is currently not in trouble" but could be in the future due to warming temperatures. The federal agency has already determined that "listing of the Pacific walrus as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act was warranted" and will make a final decision by 2017.

Closer to the West itself, conservationists are suing for protections of several species. The threats to those species vary, but climate change is cited as a factor in several cases.

"Overall, year by year, climate change is becoming more of a factor in petitions and in our analysis," Shire said.

That's good news for the environmental groups trying to win protections, but it's also unlikely to please already-rankled locals or soothe tensions that keep leading to conflicts.

"There’s potential that there will be more regulations, more limits on both the use of private land and grazing on public land," Thompson, of the Idaho Farm Bureau, said.

When asked about climate change itself, Thompson said farmers in his state are seeing the effects firsthand, but noted that future wildlife protections based on climate science would be disastrous for his industry.

"The idea is to give the wolverine a fighting chance to survive."

"It’s hard to even imagine what that would do to our agricultural community if they started listing salmon," Thompson said.

For their part, conservationists have vowed to continue fighting to protect the wolverine and hope this month's ruling leads to an Endangered Species Act listing. Though a designation can't solve the larger issues surrounding climate change itself, Bishop said it would open the door to other remedies such as increased funding, re-introduction programs, and trapping restrictions.

"It would really help eliminate the non-climate threats," he said. "The idea is to give the wolverine a fighting chance to survive."

That fight may prove to be the first part of a new, paradigm-shifting chapter for the West. When asked if people in his state were concerned about the wolverine case, Thompson expressed fatigue rather than anger.

"People are kind of numb," he said, "a little callused. They're thinking, 'oh here’s another one.'"

CORRECTION

This post originally included a photo of a barred owl that was mislabeled as a spotted owl.