1.

It was late May, and inside Ivan Wilzig’s Soho pied-à-terre penthouse, even the bricks of his parapet overlooking Houston Street were covered with black-light paint. The interior walls were littered with bright fluorescent murals that recalled Woodstock or Jefferson Airplane or any broad signifier of an acid trip. With the shades drawn, hundreds of flowers, magic mushrooms, marijuana plants, “every type of Ecstasy pill ever made,” and other Summer of Love iconography on the walls took on that alien violet hue.

Across a long hallway, the word "REVOLUTION" dripped with red paint. “It’s to remind us of the blood that was lost and the murder of the four students at Kent State,” Ivan explained.

Paper butterflies, pink, blue, yellow, and magenta, dangled from the ceiling. “They represent the free spirit of the times.”

His entire concrete floor was splattered Pollock-like with all the colors of the black-light spectrum. "It represents the chaos of the Vietnam War.”

A floor-to-ceiling mosaic of a peace sign — made entirely out of CDs featuring Ivan wearing wraparound shades and frosted tips — stood at the end of the living room hallway. Ivan did not elaborate on its meaning.

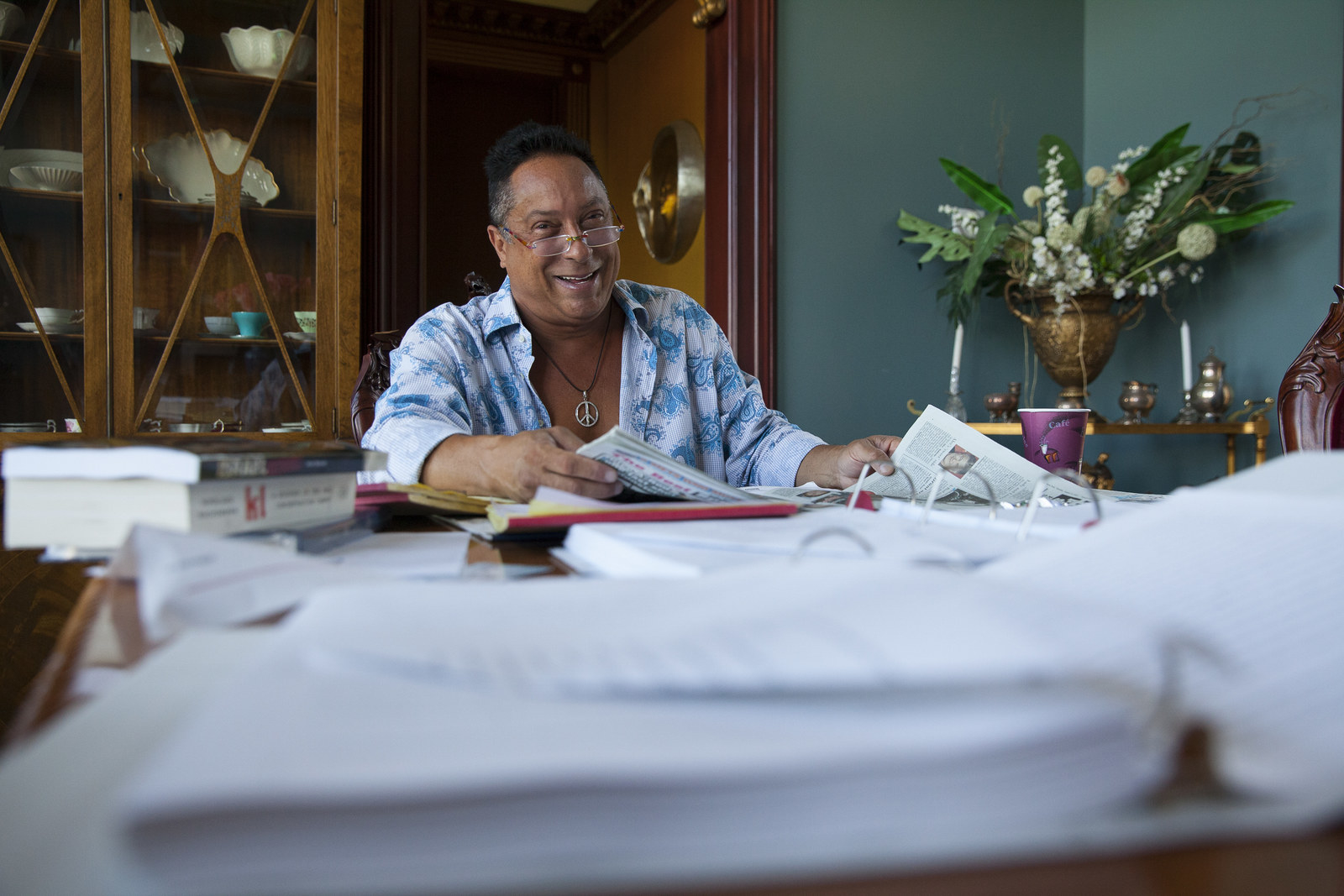

We had loose plans to see a DJ spin at a club, so Ivan, a stout man who speaks loudly and at length with an adenoidal Jersey accent, slipped off his leather sandals and went off to change. His bedroom: covered floor-to-ceiling with life-size paintings of men and women having graphic sex in all manner of permutations — the Kama Sutra writ large, 15 or so people in a neon orgy crudely illustrated with yet more black-light paint. The light switch, he revealed to me, was in the place of a woman’s clitoris: “Turn on the light?”

Ivan isn’t a celebrity, but he's been rich enough for long enough that you might mistake him for one. This would please him greatly. His self-funded techno remixes of anthems from the ’60s and ’70s have landed on the Billboard charts, and he has toiled in the reality TV mines, having been featured on VH1’s Hopelessly Rich and Destination America’s Epic Castles, among others.

He is better known by his stage name, Sir Ivan, a techno-hippy (or “Technippy,” a term he personally had trademarked) artist, who winters at the luxury Portofino Tower in South Beach and summers in an ersatz castle in the Hamptons where he hosts lavish parties each summer. The theme for this year's — his 60th birthday — was the Garden of Eden. The dress code on the invitation read: “Fig leaves or less.”

The party, Ivan told me, would require a staff of about a hundred people, tasked with taking care of security, transportation, and hospitality. In keeping with the Eden theme, Ivan would stock the grounds with apples and miniature apple pies; apple martinis and apple champagne. A total of 60 LED lights would be placed on each and every battlement of the castle, lit up like giant candles. Hundreds of rubber snakes would weave in and out of the gates by the tennis court, transformed into a giant dance floor for the 1,500 invited guests. The whole party would cost upwards of $200,000. Rumors had long swirled in the tabloids of nights filled with drugs and orgies at these late-night soirees at his estate, referred to often as the Playboy Mansion of the East Coast. Donald and Ivana Trump attended one in 1997.

“The Hefner thing I feel has already been accomplished,” Ivan told me in his medium Tony Soprano accent, with a confidence so scientifically pure it should be preserved in amber. “So now what's left is to become the next John Lennon. I’m on my way.”

The birthday gala's true purpose was to serve as the release party for his new remix of John Lennon’s “Imagine,” one of seven new remixes of “Imagine” on an album comprised entirely of “Imagine” remixes. It is the song that spurred Ivan’s entertainment career, such as it is, 15 years ago and his favorite piece of music in the world. For the single’s cover art, Ivan even re-created the famous Annie Leibovitz photo of Lennon and Yoko Ono with himself and longtime girlfriend Mina Otsuka, with whom he has had an open relationship for years. The lyrics to “Imagine” are Ivan’s holy scripture: Imagine all the people living life in peace. For Ivan, there is nothing more simple or pleasing than the idea of everyone living out their harmless carnal desires.

“The Hefner thing I feel has already been accomplished. So now what's left is to become the next John Lennon. I’m on my way.”

A few years ago, using his considerable wealth, Ivan commissioned a biography about his father, Siggi Wilzig. Written by Holocaust scholar, filmmaker, and author Joshua Greene, Siggi’s War tells the incredible story of a German Jew who survived the death camps at Auschwitz and immigrated to America, where he became a billionaire banker and oil tycoon. For Ivan, the book was the latest and perhaps most viable venture in a long line of harebrained ventures he has undertaken to write the Wilzig name in the stars.

“A year from now, we'll be getting that book on the New York Times best-seller list and turning it into a miniseries or a major motion picture,” Ivan said, noting that he has hired the best book-to-movie agent in the country. “My goal is to make it more popular than The Diary of Anne Frank.”

Ivan built his life around his father’s story. When he quit working for his father’s bank at the age of 45, Ivan jettisoned his Wall Street suits and entered the entertainment business to spread his characteristically garish gospel of peace and love. Now, in this momentous year both for scions using their inherited wealth to gain unexpected power and for the resurgent threat of Nazism, he believes more than ever that the message of his music and of his family's dark history needs to be spread far and wide — and that the former might somehow facilitate the latter.

"The more violent things are domestically or internationally, the more important my music and that book are,” Ivan told me in December, having just paid $6,500 to get the phrase “Sir Ivan’s ‘Imagine’ on iTunes” tattooed on the posterior of a 20-year-old woman from New Zealand. He may not be not the hero we need, or the hero we deserve, but he is the hero who competed on a Syfy show called Who Wants to Be a Superhero? as Mr. Mitzvah, a caped crusader for peace who wielded a small paddle emblazoned with the Star of David.

Ivan re-entered from the bedroom wearing leather shoes and pants, a blue shirt unbuttoned down to the third button where his globe of a stomach took over. For most public appearances, Ivan normally wears one of his 30 or so silken capes, each one bedazzled with peace signs (he sells them on his website for $10,000), but they were all packed in anticipation of his summer stay. Instead, a shining peace medallion rested against his winter-long Miami tan, which is deep-leathered and is, in a certain sense, inspiring.

Our limo waited outside his building, parked on the cobblestone street. It was wrapped entirely in rainbow print and paisley flowers. The word “peace” was printed in tie-dye letters on either side. He calls it the Peacemobile. As we climbed in, a guy snuck a picture of the limo from across the street. Ivan’s assistant Nat handed him his iPad, closed the door, and hurried around to the driver's seat. Today was supposed to be his day off.

The two of us rode in the limo to the club for what was no more than a five-minute drive. Ivan, both wistful and annoyed, told me that if his father hadn't forced him into the banking business for the first 20 years of his professional life, he would be “as famous as Lady Gaga by now.” There was no reason to believe he was joking.

“Ivan wants to fill his father’s shoes, he wants to be great,” said Laura Ford, Ivan's producing partner and the president of his Peaceman Music record label. “He wants to basically just remind people about peace so that we don’t end up in a situation like his relatives ended up. He lost 59 relatives — that’s a lot of people in your family to lose.”

2.

In Berlin in 1940, the 59 members of the Wilzig family were still alive, including Ivan’s father, Seibert “Siggi” Wilzig. Before the camps, the Wilzigs had moved to Berlin from their first home in Krojanke, which was then part of West Prussia, in 1936.

“I bet you’ve never seen a number as big as this,” Siggi tells an off-camera interviewer, removing his gold Rolex as he rolls up his sleeve, the inflection of his voice rocketing upward. This was around the sixth hour of Siggi Wilzig’s Holocaust testimony for what’s called the Visual History Archive for the USC Shoah Foundation. Out of thousands of interviews with survivors, Siggi’s 10-and-a-half-hour testimony is among the longest in the foundation’s collection. The faded number tattooed on his arm at Auschwitz in 1943 reads “104732.” There is a triangle underneath it denoting his Jewish faith. The number takes up more than half of Siggi’s forearm. When his son Ivan was too young to know any better, Siggi told him that he got his phone number tattooed on his arm so he could always remember it.

In this footage, Siggi is 76 and has terminal multiple myeloma. He died only four months later in January 2003 after a career as a ruthlessly intuitive mogul in the oil industry and the president of the Trust Company of New Jersey, which at the time of his death owned $4.2 billion in assets. For more than 10 hours, Siggi relays the story of how and why Ivan never had to worry about money.

Siggi recalls that they were trying to make more of an opportunity for themselves in Berlin as a middle-class family faced with an increasingly oppressive Nazi regime. The Wilzigs, along with rest of the German Jews, were stripped of their rights, possessions, and homes. Most of them began working as forced labor. Siggi, then only 14, was interned in a Berlin munitions factory at an industrial lathe, working six days, 72 hours a week. Tears stream down his face when he recalls that, after the war, the company IG Farben offered him only $1.25 per day in reparations.

Siggi’s stories are difficult to listen to. His voice quavers, but his text is exact and deliberate. There are times when he becomes overwhelmed with the clinical questions about who and where and when, trying to sort out a timeline of incomprehensible years. “[I] lived from minute to minute,” he interrupts the interviewer, chiding him. “You’re going from year to year.”

When Siggi arrived at Auschwitz, he was separated from his father, and his brother was beaten to death immediately. Two days later, his mother arrived and with a flip of the thumb was murdered in the gas chambers. “The selections were silent,” he says. “If the doctor at the table wanted you to work, he’d point his thumb to the right. If he wanted to kill you, he’d point to the left.” Siggi would evade this fate almost 20 times at Auschwitz, in part by lying about his age (he was then 16 but told the officers he was 18) and for reasons he and other survivors are beyond articulating.

Surviving the selections, the miracle of it, weighed on Siggi. He repeats many phrases during the interview (which took place over three days, filmed at his home in New Jersey). But perhaps more than any other phrase, he insists that he always believed he was going to survive. Why others did not, however, was something that he could not answer. “Ask me anything,” Siggi says, "but don’t ask me how come they took the shortest and youngest-looking through, and took the taller ones to the gas chambers. There’s no answer.”

In March 1943, six weeks after he arrived at Auschwitz, Siggi finally found his father in the camp. He had been badly beaten by the guards. He couldn’t eat. He was within an inch of his life. Siggi cradled his father in his arms. Siggi’s dark eyes focus on a single point off camera. The words of this story barely escape his mouth.

“I think I literally helped to kill my father,” Siggi says. “An SS sergeant came in with a kettle full of potatoes. They were red potatoes. You would’ve given your right arm for it. But it was all poison. It was all chemicals in it. And I fed 50 people with him, the way he instructed me. The next morning they were all dead.”

Siggi remained for two years at the camp, currying favor to work several jobs, including that of a medical assistant (he had no medical training) and as a Yiddish translator (he also learned Russian within 30 days after he arrived) and sorting the clothes and items of those who had been sent to the gas chambers.

In January 1945, Siggi was a part of one of the most brutal death marches of the war from Auschwitz to the Austrian border — a merciless trek across Czechoslovakia first on foot and then by rail in an open "cattle car" freight train. In the freezing plains, 15,000 prisoners died, but the diminutive and frail Siggi survived, again, for reasons passing understanding. Having lost a shoelace on the march, he spotted a small sapling coming out of the snow, which he then fashioned to keep his shoe from falling apart, to keep from freezing, to keep from falling behind the line, to keep from getting an infection, to keep from being shot. One sapling to live and breathe, to build a fortune. He wound up in the brutal Mauthausen camp, burying the dead with a spade. On May 5, weighing only 88 pounds, he was liberated.

Historian István Deák wrote of the few commonalities in survivor stories in his 1989 essay “The Incomprehensible Holocaust,” where each one seems to begin with “secure middle-class existence interrupted by a lightning bolt of terror" and is followed by "unspeakable agonies; quiet heroism; survival through self-respect and a desire to tell the world about it; liberation; a painful search for a new place in the world; a modest career and a contented family life, although one marred by terrible dreams.” He added, “Still, one cannot read enough of these stories.”

This is Ivan’s aim with Siggi’s War. The story lives underneath the skin and in the blood, nested in the subconscious of Ivan, surrounded by the comfort of money. What Siggi presented in his testimony was retold many times during his career at the bank. When he came to America in 1947, he had $250 in his pocket. By the ’80s and ’90s, Siggi was rolling up his sleeve again, showing clients the tattooed number on his arm as part of a sales pitch.

“Now I’m the president of a $4 billion bank,” he tells the interviewer. Siggi flashes a smile. “I was born to be president.”

3.

Among the many things Ivan Wilzig inherited from his father are his dark eyes. They are small and hidden back in his skull. Like his father, he adopts a feral and adolescent look when he says something he knows you’re really gonna like.

Ivan's music career was minted in the wake of 9/11, when a few radio stations picked up on his first remix of “Imagine.” For a moment, Ivan was signed to Tommy Boy Records before the label parted ways with its distributor, Warner Brothers, in 2002, leaving Ivan in the lurch. But his career continued apace through the aughts, with Ivan putting his Technippy stamp on Scott McKenzie’s “San Francisco,” Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth,” and Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind,” among many others.

Ivan also tackled “Hare Krishna,” for which he changed the lyrics to English and to be about loving one another instead of the Hindu god Krishna. The video for the song, filmed in the back of a hair salon in South Beach, features a scene where Ivan, dressed in an orange cape, intercedes between two men — ostensibly an American soldier holding an M15 and a Middle Eastern soldier holding a Kalashnikov. Ivan places a flower in both of their guns. The soldiers take one last look at each other, drop their rifles, and embrace.

A similar thread runs through the video for Sir Ivan’s remix of “Kumbaya.” A group of black men and women are on a beach, fighting with shields and staffs, warring tribes it would seem, wearing grass skirts and face paint when Sir Ivan appears on the horizon bathed in white light, be-caped of course, singing the chorus to “Kumbaya.” Entranced, the tribe of warriors drop their weapons and start dancing. Then they start to have sex.

Ivan defended the at best cringeworthy and at worst overtly racist “Kumbaya” video. “There was a particular problem during Darfur,” he explained to me back in his penthouse, “where blacks were killing blacks, and nobody was doing much about it. That's why there was a genocide in Rwanda, a genocide in Darfur, because there was black-on-black killing, and nobody was really paying much attention to it or getting involved. That's why ‘Kumbaya’ addressed that particular issue.”

Instead of his songs or the Peaceman Foundation — a private charitable fund through which Ivan funnels any profits or donations he receives from his music career — Ivan himself often becomes the conversation piece. Laura Ford thought this was only a boon to his message. When she came out as trans, Ivan was there, supporting her financially, and it was in part due to her transition that Ivan was inspired to become heavily involved in LGBT charities like the Trevor Project. “Whether it’s his capes or his castle, he spins that into something that is positive and awesome, which is peace.”

His Southampton castle — the 15,000-square-foot structure with battlements, towers, a half-moat, a drawbridge, seven waterfalls, two fire cauldrons that flank his infinity pool, tennis and volleyball courts, indoor and outdoor spas, nine individually themed bedrooms, an eight-car garage that doubles as a dungeon, and enough gilded patio furniture to rival a Sandals, and on whose walls hang many vaguely medieval paintings of kings and knights whose artists and provenances Ivan cannot recall — is part and parcel with his identity.

Ivan’s message of peace and charity has long bumped up against his reputation as a consummate Hamptons playboy. His open relationship with Mina Otsuka, his “best friend and soulmate,” is reinforced with images of Ivan surrounded by women. In a documentary Ivan produced about himself called I Am Peaceman, there is a montage, a rapid slideshow of women who fly by, meant to imply Ivan has in one way or another been with all of them.

Alan’s old room became the afterparty room, filled with lasers, a tray of cigarettes, and a fishbowl full of Trojan Magnums.

“On the most superficial of levels, the Wilzig boys are both out looking for girls,” Ivan’s younger brother, Alan, told me. “I’m finalizing a divorce from a woman I’ve been with for 25 years, whereas Ivan has been with 25,000 women in the last 25 years.” Alan is 51 with two kids, lives in upstate New York, and is known for owning one of the country’s largest private professional-grade racetracks in his yard, which he built for $7.5 million. Alan has a new girlfriend now, 23, soon to graduate from Duke University, and who “happens to be a piece of ass, but she’s a genius.”

It was actually Alan who built and designed the castle in 1997. As soon as its 50-foot stone and stucco walls were erected, the two brothers moved in, and within weeks, weekend raves were de rigueur: weed, Ecstasy, trance music on the castle’s own dance floor, and sex in the infinity pool until the sun came up. Their white-linen party lifestyle often landed the Wilzig brothers in the tabloids or the New York Post's Page Six, portrayed as two millionaires elbowing their way to the elite by the sheer noise of their personalities.

Their mother, Naomi, for years the owner and director of the World Erotic Art Museum in Miami, died in 2015. She left behind a legacy of a collection, born of a request from Ivan to get him something sexy for his bachelor pad in the ’90s. Siggi came to visit the Hamptons castle only a few times, because the whole display was never much to his liking. In the early ’00s, Siggi tried to sell it because of its lurid reputation and its perceived collateral effect on his bank. It was on the market several times during this period, but it never sold.

Things tapered off after Alan had kids and Ivan bought his half of the castle. Alan’s old room became the afterparty room, filled with lasers, a tray of cigarettes, and a fishbowl full of Trojan Magnums. It was no longer the Wilzig castle, but Sir Ivan’s castle.

Ivan’s sister, Sherry, who stayed out of the tabloids and invested in charity work in New Jersey, believes the family has defined itself by Siggi's survival story. “It does affect your worldview, your responsibility, your goals," she said. "It was a big part of our lives to make our father happy and do what he wanted, because you knew what he went through.”

Siggi was the inspiration behind Sir Ivan, the spur to open the Peaceman Foundation, to give the money to those who suffer from PTSD, because while Ivan told me his father was never diagnosed with PTSD, “he still had nightmares from the camps, depression, flashbacks, nervous anxiety from it.”

After attending the University of Pennsylvania and Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University, Ivan decided against becoming a lawyer. But he was bribed by his father not to go into show business — cars, houses, limos, drivers, his own table at the 21 Club, anything so Ivan would have a respectable and stable career. “He threatened to disown me,” he said.

Deferring his dream, Ivan worked at the Trust Company of New Jersey as the head of marketing throughout the ’80s and ’90s. He showed up to work with the archetypal son-of-the-boss attitude. He slept through board meetings, the smell of the club masked by his neatly pressed suit in the morning. He came and went as he pleased.

But while Ivan was still at the bank, his father remained quietly inconsiderate of his passion, largely unimpressed with his various demos, and perturbed by his nightclubbing lifestyle. It wasn’t until Ivan had earned the interest of Tommy Boy Records that his father did what Ivan referred to as a “U-turn in the Lincoln Tunnel.” He showed Siggi, who was in the hospital being treated for cancer, that “Imagine” was on the Billboard charts. Siggi didn’t quite understand it. The nurse by his side explained that Billboard is to the music industry what the Wall Street Journal is to the banking business.

“The guy only recognized success,” Ivan told me. “He didn't want a son that was an aspiring this and an aspiring that, but the minute that I had any success: ‘Congratulations. I knew you could do it. How much of an advance did you get, I'll double it!’”

4.

As I drove out to Southampton to visit Ivan at his castle in June, out to the part of Long Island where local ordinance states that two Range Rovers must be parked at a Starbucks at any given time, I worried about how I should react to his naked dragon-lady sculpture — I didn’t want to oversell it. A simple “Oh, wow” should do.

My rental car idled through the “largest gates in the Hamptons,” and the full-time castle manager led me behind the estate where the sculpture rose up out of the infinity pool. It glistened in the water, the rainbow hues of its scales like copper oxidized with rich-people oxygen. The sun danced on its golden wings. There was nothing ersatz about it.

Ivan greeted me, still impressively tanned and now shirtless, wearing a pair of small blue Versace swimming trunks. He sweated a lot, but it was a humid, windless, and sunny day in Southampton. Sometimes while he spoke, he paced back and forth with his hands behind his back, reality-TV regal, one of his only affectations that feels learned as opposed to lived. Otherwise he was un-self-conscious and silver-tongued, speaking quickly, loudly, and without hesitation. He lives in what I imagined to be an anxiety-free world where impulse bypassed any visible consideration and simply became a result. Subtlety is for people who can’t get what they want by saying what they mean.

“If he's only listening to mindless tracks without vocals, that's not going to keep him from blowing up a gay nightclub.”

This is reflected in his art. For Ivan, there is a one-to-one ratio with music and its attendant result. Violent music begets violent acts, just as much as the strains of John Lennon’s “Imagine” will rid the world of its possessions and inspire its people to live as one. In the wake of the mass shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Ivan told me he was convinced that if they were playing his remix of “Imagine,” shooter Omar Mateen might have changed his mind.

“It was obviously some emotional problem that he was having,” Ivan said, “so how could listening to a song that's very positive about everybody being free and happy and healthy and living together as one have had a negative effect? But if he's only listening to mindless tracks without vocals, that's not going to keep him from blowing up a gay nightclub. If he's listening to just EDM music with no vocals like most of the cool DJs are playing, that’s not going to change a generation.”

Ivan spent $16,000 on mezuzahs for the place, including a large, castle-shaped mezuzah on the front door. There are two stone peace signs embedded in the pavement, and a brilliant 5-foot diamond-shaped mosaic made of windshield glass refracting the sun coming through floor-to-ceiling windows that lead out to the veranda. From this height, you can see past the trees of his property to the sailboats of Little Peconic Bay, and the Long Island Sound just beyond it. “I’ve always wanted to perform up here and feel like Caesar, you know?”

Ivan insisted we go for a swim in the pool. He let me borrow something to wear, a beige and plaid Burberry number that was more boxer-brief than swim trunk, but considering the normal attire is usually nothing, this felt adequate. It was late afternoon and the golden hour made the facade of the castle seem doubly rich.

Ivan waded around the pool in little circles, talking about the various charities he’s involved with. He donated over $100,000 to the Trevor Project. He became indignant when thinking about why he is not played on the radio, or more popular among the dance or pop scene, because it’s all for a good cause.

However, being an artist who does mostly cover songs, whose royalties go into the pockets of Buffalo Springfield or the Lennon estate, there has been far more money going out than coming in. “I’m usually paying 5, 6, 10, 15 [thousand] for a remix,” Ivan said.

In total, Ivan said he has probably spent a million dollars on his own music career, the purported sole goal of which is to raise awareness for LGBT, PTSD, and anti-bullying charities and foundations. His recent original single, “Kiss All the Bullies Goodbye,” features Taylor Dayne and was produced by Paul Oakenfold. It cost Ivan $40,000 to get Oakenfold on the track — a bargain because the song was for charity. Tack on the budget for the video, promotion for the record, PR, and more and the costs begin to add up.

“If we don't have that kind of record that reaches the masses, then my message about PTSD, LGBT, bullying, and violence don't get heard. My messages about the Holocaust and genocide don't get heard. Nothing gets heard unless I get a Top 40 radio hit.” He paused, his attention on something off in the distance. “Or I get my own reality show, which I'm also working on.”

In searching for a way into Ivan, it is often easier to find ways out. Club and techno music to him are the life force of this generation, the political and spiritual wave upon which young kids will ride, just like rock ’n’ roll was in the ’60s and ’70s. “I hate rap and hip-hop,” he said, moving his hand blithely through the water. “Everything it stood for, everything it stands for — it’s just thug music for thugs. Every convict in every prison in America is listening to hip-hop, not high-energy dance music. As long as it's associated with gangsters, and thugs, and convicts, there's nothing you can say or do to convince me that it's a good thing.”

I asked for three minutes to rebut. He cut me off within seconds.

“The first thing you're going to say is that it's homegrown, it's organic, it's poetic justice for them to get their story out, because that's their reality — and I understand that, but do it through poetry, don't claim it to be a music form. I don't think there's any culture to it. I find the entire thing uncultured and barbaric.”

He crossed to the edge of the infinity pool, looking toward his tennis court. The gilded patio furniture, the facade of the castle, the naked dragon-lady sculpture, everything was bathed in gold.

5.

In his book After Auschwitz, historian and theologian Richard L. Rubenstein explored the crisis of God’s tangible existence in the wake of the Holocaust. He wrote: “We stand in a cold, silent, unfeeling cosmos, unaided by any purposeful power beyond our own resources. After Auschwitz, what else can a Jew say about God?”

Siggi had a sign in his corner office: “Free men who forget their bitter past do not deserve a bright future.” He remained an Orthodox Jew his entire life. As his father died in his arms, the last words he spoke to Siggi were “You kept kosher,” referencing his time in the Berlin munitions factory when it was then still possible to honor yourself before God through self-sacrifice.

But to Siggi, his higher power was success. “He would invent whatever persona was needed just to survive,” said Greene, the Siggi’s War author. “So the perception of success, expertise, reality, it was much more important than anything else. It is what kept him alive.”

The only way that Ivan can justify a music career in his father's eyes is if he becomes a phenomenal success at it.

Greene shared István Deák’s caveats about the tropes of retelling another Holocaust survivor story. Whether Siggi’s War will become more popular than The Diary of Anne Frank remains to be seen. But for Greene, there were enough transcripts from Siggi’s many speeches and journals, and enough friends and colleagues from Siggi’s time as an oil tycoon and bank owner to form a unique narrative: a new David and Goliath story. Mostly, though, it was the passion of Ivan Wilzig that spurred Greene to take the job.

“This is Ivan's project,” Greene told me. “His purpose was to honor their father who was the pinnacle of workaholic, which is not unusual. Many people who came out of the camp experience are baffled as to why they survived and others did not, but are convinced that they had a moral, ethical, and religious obligation to work very hard to earn their life and to tell their story.”

Greene admitted that for Ivan, this book was more than just the proliferation of Siggi’s story. “There’s a lot of ego involved here,” Greene said. “The only way that Ivan can justify a music career in his father's eyes is if he becomes a phenomenal success at it. If you're a success, Siggi Wilzig is going to appreciate you.”

6.

When I returned to Ivan’s castle for his Garden of Eden party in August, Nat, Ivan’s assistant who had been working on his day off back in May, had the fast walk of a stage manager in crisis mode. He was the sergeant of party planning, ordering security, caterers, servers, bartenders to their tasks, telling a group of three young women they needed to be constantly cleaning up any cigarette butts or empty cups up the dance floor — to, if nothing else, look busy. The din of the party grew.

There were indeed LED lights on the castle, each programmed to look like a flickering candle, and the tennis court had been transformed into a “snake pit” where there were, indeed, hundreds and hundreds of rubber snakes inserted into the chain-link fence and placed about the yard. The “fig leaves or less” dress code was honored by a handful of guests in thongs or tassels with plastic leaves wrapped around hips and chests, but most of the guests wore something broadly sexy, green, revealing, and biblical.

It was as if you'd given a teenage boy half a million dollars to throw a “sexy party.”

A group of women wearing little more than angel wings danced at the edge of the pool, while naked men and women dressed as snakes writhed around the outdoor cabanas. The DJ played a deep house remix of Bob Marley’s “Could You Be Loved.” It was as if you'd given a teenage boy half a million dollars to throw a “sexy party.”

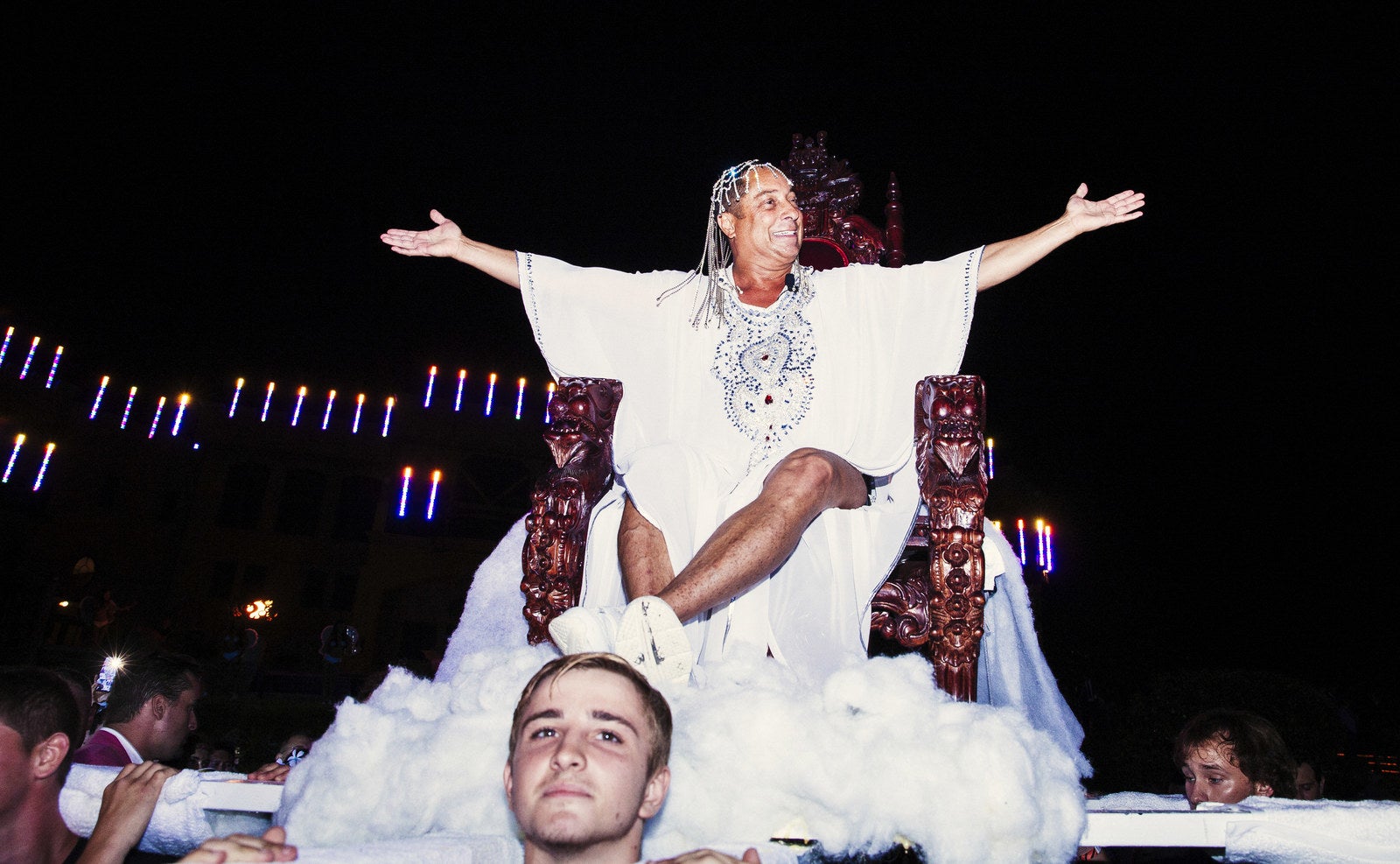

At 9:30 p.m., with the humidity much thicker than the dance floor, the DJ announced that it was time to “sing 'Happy Birthday' to your god.” It was at this point that Ivan appeared on the veranda. He was wearing a sheer and flowy gown that was somewhere between an angel robe and a kurta, white Velcro shoes, a crystal crown that rained down over his head, and a silver thong. The guests sang a gravely dispirited version of “Happy Birthday,” the candles were “blown out,” and Ivan went into his club remix of “Imagine.”

Ivan lip-synched on the veranda, overlooking the crowd. He gesticulated wildly, waving his arms to and fro, signifying very little. Amid all the skin and money, the fake status and privilege given to this vague value of sex, among Hamptons bros and such an ostentatious display of wealth, here we were listening to a song written and recorded by an abusive millionaire in his enormous Georgian mansion, a song that condensed the tenets of humanism into empty platitudes. But is anything so delicate, so subtle as to try to unravel the horror of the world through anything other than one of the most covered and performed songs of the last half century? A blast of bass in my chest, camera phones in the air, a man in white overlooking us all, asking us to believe in something that we all know is impossible.

As the beat went on, Ivan joined his subjects on the dance floor sitting on an ornate wooden throne placed atop a litter carried by seven truly mirthless young men who he assured me were all over 18 and who were hired to do only this one task. “It is I, your god!” Ivan yelled, his Jersey accent sounding particularly farcical in this moment, something out of Mel Brooks’s dream journal. “Spin it around, you lazy guys. Let them see what God looks like from every angle!” He continued to snake his way through the crowd as a retinue of professional and amateur photographers angled to shoot. There were smiles, laughter, gobsmacked looks. “Who wants to get naked? God says it’s OK!”

As I left the party, there in the front yard was a towering 40-by-80-foot sign normally meant to be dragged behind a crop duster. It billowed in the wind, larger than the castle itself, blocking the trees that line Ivan’s property. The banner read: “Sir Ivan. ‘Imagine.’ Download Now.” ●