My very first memory is of being really tiny and dancing the Rabbit Dance, named for what the dance was inspired by—the movements resemble those of rabbits. I’d always dance it with my twin sister. Mama always told me to listen to the beat, move my feet with the beat. And then, my older brother would join us, and he’d hold both of our hands and dance with us. It was probably the last time all of my siblings, my mother’s children, were together, when we were all dancing.

When I think about that, it makes me happy because we did it as a family. It gave us all joy, and it still does for me now. Sixty years ago, we would never have been able to dance. Now we have that right, that freedom, to experience something that our elders would’ve been beaten for.

I’m from Cheyenne River Indian Reservation. My grandfather, Harry Charger, was chief of the Itazipco band. When he was younger, he was a pipe maker. He learned it from his grandfather at a very young age. And he couldn’t tell anybody about it, he couldn’t tell his friends or his family members. He had to keep it secret. He always told me he felt like he had to hide who he was. He told me to go to powwows, go to Sun Dance, take advantage of those opportunities because there are so many who never got the chance to go. He told me, “You’re never too young to learn, never too young to understand what your people have been through.”

A lot of adults think that young people don’t understand or don’t listen. And we may not understand in that moment, but as we grow up, we carry that knowledge with us, and we begin to understand. And we won’t have to go on living in ignorance. I think that’s what I was spared. My grandfather talked to me like I was an adult, like I was old enough to hear these things.

On my mother’s side, I have five siblings, and on my father’s, I have ten siblings, but I only have one full sister, and she is my twin, Jasilea. The siblings I have from my father, I’ve only met one. My mother’s kids were split up among family members because my mother couldn’t take care of us all.

We got to play with each other, but we rotated through family members and foster homes until I was thirteen. I’m practically related to this whole reservation, so it’s like everybody’s my cousin. The community helped a lot. People would come by and say to my mom, “Hey, you need someone to watch your twins?” Or, “Do you want me to take them to the park?”

The foster homes were located on my reservation because the tribal court is really strict with trying to keep tribal members, children, on the reservation with Native American families, close to their parents. So I was placed in some rural communities, all within a sixty-five-mile radius of here. Some of them were my father’s family. They’d tell me stories about my father, what he used to do when he was my age. And they’d have old pictures. Or some of his friends would come over and babysit us. They’d talk about our dad. We didn’t get to know him because he died two months before we were born.

Oh, my mother! She’s a very strong, independent, stubborn woman. She’s like a bear. She takes care of her children with the sheer force of will, and she lays down the law. She and I didn’t really see eye to eye as I was growing up, but as a young adult now, I try to be around her as much as I can, because I want to have her strength. No matter what happened to her, she kept going, raising five kids.

Their fathers weren’t around to help, and she still did it. We could’ve gone to the adoption agency, or she could’ve aborted us, but she chose to keep us, and she toughed it out, and she raised us the best that she could. Someday I want to be half the woman that she is.

When I was thirteen, my aunt died of diabetes in her sleep. And one of our traditions is bloodletting for healing. We cut ourselves and we let the blood return to the earth. It’s a way for us to get all of our bad emotions, all of our bad thoughts, out. Staff at school saw my cuts.

But they didn’t understand them. They thought I was trying to kill myself. And so they called the Department of Social Services and got me taken away. Instead of trying to understand my tradition, they instantly thought there was something wrong with me. They said I was a danger to myself and other people.

They called the Department of Social Services and got me taken away. Instead of trying to understand my tradition, they instantly thought there was something wrong with me.

Social Services took me to Regional Health Behavioral Health Center, the highest-security facility that you can go to that isn’t correctional, and I was there for two weeks. At Regional Health you don’t get to have your shoes, no personal clothing, and you don’t get to talk to people or go outside. There are no windows. Everything was controlled.

From there, I got sent off to Canyon Hills, a mental health facility for kids in Spearfish, and I didn’t see my family again until I turned eighteen. We went to school, ate, and slept in the same building. It was a Christian facility, so they took us to church every Sunday. But I appreciated that there was also a cultural adviser for Native American kids, and there was a sweat lodge nearby. So I still got to be connected with that.

I thought they were going to take just me away. But they took my sister too. Separated at thirteen. That was our first time being away from each other. In our culture, you’re not supposed to separate twins because they have a bond, a connection, and when they took us away from each other, we both got sick. She got walking pneumonia, and I was just really, really depressed. Like, it detached something. I felt a part of me was getting torn away. It physically hurt me. Because I’d always had her there; I’d always had someone to talk to. And that traumatized me.

Low-income Native Americans receive the majority of their behavioral health care through the Indian Health Service, tribally operated programs, and off-reservation facilities, financed by a combination of local, federal, and tribal funds. In treating a “special minority population,” these off-reservation institutions receive more federal funding to treat Native patients than they do for non-Native residents.

The facility wanted Native Americans to be admitted, to make money for the facility. That’s what I felt I was to them: just more funding. They didn’t care about my physical or spiritual needs. They didn’t prepare me to be successful out of the facility. They don’t prepare you for life; they can’t teach you anything about life in there.

But when you turn eighteen, the system just kind of loops you out. My family didn’t really know me. They knew me when I was a child, but they didn’t know me as a young adult, and so they had a hard time trusting me or welcoming me back into their homes.

When I came back, for example, I knew nothing about sex. There were sex-ed classes, but they didn’t prepare you for what actually happens. I was trusting. I came back like, Oh, I’m with my people. People who actually care about me. People just like me. I was completely wrong. I trusted some people who I knew when I was younger, and they got me drunk, and I ended up getting raped. It was on my eighteenth birthday. And that was my first harsh experience—that’s what life really is. It’s not what they teach you in sex-ed classes. It’s not what they teach you in a textbook. I felt like I was robbed, that the system let me down.

“I KNOW WHO YOU ARE”

I wandered around the community for a while, homeless, couch-hopping with some friends. And then one day, my friend Kalen’s cousin, Wotila Bald Eagle—we knew each other a little bit—he asked, “Do you have a place to stay tonight?” and I was like, “No, I don’t.” And he said, “Well, you can come home with me.” It was kind of sketchy. I thought he lived in town, but he lived on the west end, which is sixty-five miles west of here. He was driving me out, and I was just thinking, Oh my God. It freaked me out. Where is he taking me? What’s gonna happen to me? And then I fell asleep. I woke up, and we’re at his grandfather Dave Bald Eagle’s ranch house. It was raining when we arrived, and Wotila brought me to his grandfather and he let me introduce myself, saying, “She needs a place to stay tonight.” And without even really asking where I’d come from or what my situation was, his grandfather Dave said, “There’s a room right there, there’s clean towels for you to shower, there’s food in the fridge. You can go take a rest.” And that really caught me off guard, like, Whoa, he wants to help me.

I was only supposed to stay there for the night, but Dave was like, “You can stay ’til the end of the week.” And I ended up staying there for four months. He didn’t ask, “Where’d you come from? Where are your parents? How come they aren’t helping you?” He let me tell him when I was ready. And he was really open.

He said, “You could live here if you want to, my house is open to you.”The west and east ends each have two chiefs, and Dave was one of them. My grandfather was one of them. Dave told me once he’d heard my name, he knew he had to help me. He was like, “I know who you are, I know your family.”

He always sat at the end of the dining room table. He just sat there and had his coffee. One day, I grabbed a cup of coffee too, and I sat right next to him. We were both just sitting there with our cups of coffee for the longest moment. I just started talking, and he didn’t say anything, he just glanced up at me. And when he looked at me, I felt calm. I didn’t feel so nervous.

When I got to the points where I thought I’d cry, he’d just look at me, and I’d get my composure, and I would keep telling him who I am, where I came from, what I experienced. And he didn’t judge.

The facility wanted Native Americans to be admitted, to make money for the facility. That’s what I felt I was to them: just more funding.

I told him I came from a psychiatric facility. He didn’t think I was crazy; he didn’t mistrust me; he didn’t think I was going to steal anything. He just felt compassion for me. And that was the greatest feeling, not being judged. Dave knew a lot of people who went through the boarding schools, a lot of people who went into insane asylums because they were spiritual people.

Colonialists felt that people who “had medicine” were crazy, and they locked them up. And he was telling me stories about some of his friends who went through that. He was like, “You’re not crazy, they’re just trying to silence you, doing the exact same thing to you that they did back then. Kill the Indian, save the man. But you survived.

And you found your way to me, and I was meant to help you.” And when he told me that, it made a lot of sense to me.

Growing up, I felt like there was something wrong with me. The staff at the institution always told me, “If you were okay, you wouldn’t need to be in here. If you were normal, you wouldn’t be here, people wouldn’t have sent you here.”

And hearing that from age thirteen to eighteen, all those adolescent years—they drilled it into my head that I have to take substances in order to be okay. For a long time, I felt that—I’m a danger. I needed alcohol, different kinds of pills for what they diagnosed me with. They brainwashed me to think, I’ve got to take this, I’ve got to not be me. And Dave told me, “You don’t have to take those anymore. If you don’t want to, I’m not going to make you.” I threw them all away, and he helped me! He was just like, “Go outside.” I finally had somebody in my life again to really support me, who had my back.

I HAD TO STAND UP FOR MYSELF

In the summer of 2015, when I was nineteen, one of my best friends killed herself. Her name was Candi. She was three years younger than me and really outgoing, spontaneous, always ready to have fun, laughing.

I came back for her funeral and then a couple days later there was another funeral. We had a suicide epidemic here, and we had a couple murders, and it took a lot of my friends. A couple of our women went missing. We were losing our youth at a very alarming rate. I was worried about how many of us would be left and what would happen to the ones that were left bearing the tragedy of their classmates or their relatives not being here. It was heartbreaking, and it was suffocating.

We felt like we were drowning in drug addiction, violence, murder. No one was listening to us, no one was teaching us. We didn’t have a voice, so some of us decided to silence ourselves. And I got the feeling that I had to stand up for myself. A couple of my friends started One Mind Youth Movement. It started out with a couple kids meeting every Wednesday, talking about what happened that week.

Our reservation looks at drug addicts as the enemy. If you get caught, it’s like, “We don’t want you here no more.” We were like, “It’s not their fault. They’re sick, they need help.” And we were devising ways to support them. If we can’t make them stop, how can we support them so they don’t endanger themselves, or overdose, or pass out somewhere, or get raped? We were trying to find the best ways to look out for one another. And we made an agreement that if we see a kid drunk or a little girl walking with five dudes, we would do something. We had each other’s phone numbers; we knew where each other lived.

And we had mentors who were willing to support us, open up their homes, who’d even come to pick us up at two o’clock in the morning. I was always worried about my friends because they’d get drunk and beat each other up. Or they wouldn’t have anything to eat. Or their parents would kick them out. I always told them, “Hey, if you ever need a place to stay, or if you’re in jail, or if there’s something going on, call me. I’ll help you.”

WE JUST HELD THAT SPACE

That summer, I started seeing a lot of things in my community through a different lens. It was eye-opening to see what we were going through. And that’s when the KXL protests started happening.

In July 2008, TransCanada Corp and ConocoPhillips, co-owners of the Keystone Pipeline (which runs through North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas) proposed a major extension to the network. Dubbed “Keystone XL,” the addition was designed to help the pipeline move hundreds of thousands of barrels of crude oil from Alberta to Texas. Because Keystone XL would cross the US border, the State Department was tasked with determining whether the development was in the country’s best interest.

While TransCanada claimed that the Keystone XL pipeline wouldn’t cross any reservation or tribal trust lands, the pipeline’s proposed route did intersect original Lakota reservation territory established by the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. Cheyenne River Indian Reservation is just downstream from where the Keystone XL pipeline was set to cross the Cheyenne River, and the tribe feared that a spill could contaminate its waters.

My cousin, Joseph White Eyes, was at the Keystone XL pipeline camp in Rosebud. Joseph always asked me to come, though I was still in that “I don’t listen to nobody” phase. But I started getting more involved. He wanted to teach us community organizing.

We did an Indigenous Rising march from this area. The march was about uplifting the youth and giving them power to voice what they had to say about KXL. We made banners, we got our own permits, we organized with each other.

We videotaped and documented the whole thing. We held this on Highway 212. For about two hours, we were singing songs, doing rain dances. And we just held that space. No one bothered us or told us to move. They just waited, took a different route. Some of them started walking with us. Even the homeless people stood with us. That was our first taste that we can do things, that people will listen to us if we organize and communicate and work together.

And it taught us unity, that if we put aside our differences, we can come together for a common goal. It was a small thing, but we got it done, and that really kicked us off.

And we celebrated when the KXL pipeline was denied.

Just a month after Obama rejected Keystone XL, the US Army Corps of Engineers for the Omaha District published a draft of its plan to approve the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) route under the Missouri River, which would travel nearly 1,200 miles from North Dakota’s Bakken oil fields through South Dakota and Iowa to reach a terminal in Illinois. One section of the pipeline, set to cross the river just north of the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation, became the center of a fight over how the pipeline’s route was evaluated and approved by the federal government.

For about two hours, we were singing songs, doing rain dances. And we just held that space. No one bothered us or told us to move. They just waited, took a different route.

Members of the Standing Rock Sioux said that they were not adequately consulted about the route and argued that the pipeline’s proposed path, under a river reservoir called Lake Oahe, would jeopardize their primary water source and compromise tribal fishing and hunting rights. In addition, the tribe argued that the pipeline construction would extend damage to their sacred sites near the lake, further violating their tribal treaty rights.

Just a few weeks after that march, there was a broadcast on multiple radio stations here from Standing Rock.

It was like, “Hey, there’s a call out.” The people at Standing Rock want people that fought KXL to come and share their experiences. We were like, “Alright!” We brought our youth movement. And, surprisingly, we were the only ones there—the people who organized the call and a bunch of kids from Cheyenne River Reservation. We sat there, and we waited for a whole hour. Nobody else came. Not our chairmen, not akichitas, who are the men we send to defend us, not medicine men, just us.

The organizers didn’t take us seriously and said, “You’re just kids.” But we showed them how to target youth to be more active, because there’s a lot more of them, they’re more agile, they can do a lot, they can get things done fast. They’ve got a fresh outlook on things, are more creative, intuitive. We tried to tell them, “You need to get the youth here.” And they’re looking around, “Well, where are our youth? They didn’t come to the meeting.” Chase Iron Eyes was there.

At the end of the meeting, Ladonna Brave-Bull Allard stood up and told her story. Her son was buried on her land. A lot of her medicine was on her land. She just started crying and said, “I need help. My land is right next to the river, and my son is buried there. My land is open to you; you can come camp.” So we helped them create a plan.

We shared how to better communicate with their youth. You know, not just to say, “You have to be here,” but, “Can you help out? If you’re an artist, can you make our banner? If you’re a cook, can you do bake sales?” Older people, it’s hard for them to really connect and talk with the younger generation. Because we’re so tech savvy, we want to make memes, do Snapchat. Social media is one of the tools that we told them is most useful. We helped with different programs, different apps that work well for making posters, or doing podcasts, videos. Those are the things that we shared.

The very first camp was called Sacred Stone Camp. All the chiefs, all the men, pipe-carriers, they came out and set up like twenty teepees. But nobody stayed. The only person who was up there camping was our mentor, Joye Braun. She has a lot of medical problems; she can hardly walk. And we were like, “She’s up there by herself? What the hell?!” So we asked our chairman for some money for gas and food. We bought some cold cut meats, some sandwiches, chips, some Gatorade.

Our plan was just to stay up there for a couple days. But once we saw Joye up there alone, we ended up staying for a whole week. Nobody really believed in us. They were like, “The pipeline’s still gonna go through, what are you five people gonna do? You can’t stop it.” But there were people who supported us. They’d bring us food, water. A couple of men broke apart their old corral and gave it to us for firewood.

We didn’t have a GoFundMe, we didn’t have anything like that. The people who supported us, who came out to check on us—to make sure we had blankets, that we were okay, that we had water— were the people of Standing Rock. And I think that’s really what motivated me to keep camping there. It was a calling. I thought, No one else is going to do it, so we’ve got to.

It was mentally challenging. We had no cell phone service, no TV, no YouTube, no nothing. We didn’t know anybody there. We didn’t know the community. But then we turned a spiritual corner.

We thought, We’re here, this is like a prayer. And it kind of reconnected all of us to our heritage because that’s how we used to live.

We were nomadic. We went without a lot of things—salt and sugar, Kool-Aid, pop. It taught us self-discipline, a lot of patience. We started gradually gaining people. Four months into it, we had twenty people living with us. And all from different places. But we had to learn how to work together, how to live with each other, how to listen to each other. Kalen, Joseph, and I, every night, we’d come together after a meal and discuss what happened that day. We would just be doing our chores—hauling wood, going to get groceries, helping trap fish, going swimming, taking care of the little babies—doing what the old people couldn’t.

Eventually, we had a lot of non–Native American visitors. Some of the traditional camp leaders didn’t want white people around at all. But we told them, “We need our non-Native allies.” Because we can’t just shut off the whole world. We need to show them that this affects all of us. We’re here for the water. We’re here to stop this pipeline. It always came back to that.

We also ran up against questions like, How should the camp be run? What are the protocols? During ceremonies, the traditionalists would try to say women should always wear dresses in the camp and shouldn’t talk to any of the men. Joseph and I were like, “So that means I can’t talk to you. That’s a barrier for communication.”

A lot of my friends, they put themselves on the front line and got arrested.

There’s proof in our culture, pictures, stories about two-spirit women doing things that men did. Going to war and taking their place. Today our culture is very masculine. We have a lot of male leaders. And I really wanted to encourage the younger women. You don’t gotta sit in silence. You don’t gotta hush when a man tells you to hush. You’re an individual. And you can live your own life, because we have that freedom now. A lot of women fought for that freedom. And I wanted to honor that. Kalen had my back, Joseph had my back. They all supported me. We were like, “We’re the young generation. We’re going to lead ourselves.” And we held fast to the Seventh Generation Prophecy that we are going to be our own leaders.

That we’re going to break the chains of oppression, of racism, of the colonialism that have chained us to this reservation, and break the feeling we can’t do anything, and we don’t matter, and that no one’s going to listen to us. I wanted to show the youth that they have a voice. Use that voice, because you have a lot of power. I tried to show them that by doing it myself.

I never got arrested up there because people saw me as a spokesperson, someone to tell their stories. A lot of my friends, they put themselves on the front line and got arrested. And they told me, “No one’s going to tell our story if we’re all arrested. Get out there; get invited to marches, protests in Washington, DC, New York.” Tell people what we do and what we did—that was my role. It was hard to watch my friends go through that much suffering.

One of my friends, Trenton—he was like a brother to me, we started on this road of protesting together. I watched him get dragged out of Inipi, a sweat lodge, a sacred ceremony for us. Women go in with a shirt and skirt, men just in trunks. And he didn’t have trunks, so he went in with just his boxers. The Morton County police and a private security company called TigerSwan tore down the whole sweat lodge and dragged him out, and they had him sit on the side of the road wearing nothing but his boxers. And it was freezing cold that day. They said that we were trespassing on government property. We told them, “Just let us finish our ceremony, and we’ll leave peacefully.” But they didn’t wait for us to clear out. They just attacked and surrounded the whole camp.

The people who were on the outside made sure the women and children got out safely. And I watched them get taken down. It was horrible. My sister-friend Malia—she’s Hawaiian, a protector of Molokai—Lauren, who’s Jicarilla Apache, a protector of Bears Ears and their sacred mountains, Tashina, three other women, and I were standing in front of the agitators who were throwing rocks at the police.

We were worried people around them might get hurt, so we took it upon ourselves to make a barrier between the cops and the agitators and everybody else. We mentally prepared ourselves. They’re gonna throw racial slurs. They’re gonna beat us. They’re gonna yell.

They’re gonna mace us. We chose to put women on the front line, saying, “Are you going to beat women? I’m probably the same age as your daughter. Would you do this to your daughter? Would you let somebody do this to your daughter?” We’d shout at them, “You’re supposed to protect us, you’re the police! Why are you doing this?”

And a lot of them would stop; a lot of them would have to switch out with other cops. They couldn’t do it. But there were those who had no remorse. They would shoot rubber bullets at us. One woman, three down from me, got shot in the face with a rubber bullet. We were all women, mothers, daughters.

Seeing all that happen and seeing men doing it to us? It was hard to put myself in that position of abuse and take it with no retaliation. It was very degrading. I always tell younger women, “Never let a man lay hands on you.” But we were there in prayer and we just took the hits, we took the beatings, we took the mace. We held together. I got maced like five times. My face was burning. And later that day all that mace ate at my skin and there were just big old red rashes all over my face. Kalen got shot with rubber bullets twice in the back. We had no weapons.

On the last day of the camp, Kalen, I, and another one of our friends stayed—we wanted to get arrested. But our friend’s mom and some of the elders we hung out with were like, “No. If you want to stay, just witness what’s happening to people. Videotape it. Remember it. And go home and tell people what happened.” I was like, “I don’t want to do that, I want to go with you guys. Let’s go down with it.”

But they said, “No, no, no. We’re old. This is our moment. We’ll go down for you, but you need to go home and tell them what happened here.”

We saw the last fire keepers get arrested. And our friend’s mom got arrested. None of us had weapons. But Morton County and other county police, border patrol were there too, and they were coming up on us like we were armed. They came up with full body armor, with SWAT gear and a bunch of guns. I felt like they were going to literally kill us all. They had helicopters with the guns on the side. We were like, “Why do you need those?” I was really scared, thinking,

What are they going to do to us?

A lot of people were trying to get their stuff and go. And we tried to help as many as we could and observe as much as we could. Then, the police finally pushed us all to the river. We were all on the frozen river—it was basically a peninsula off the Missouri River that ran next to the camp. We had this rope stretched across it for people to hold onto in case the ice broke. And the police were cutting that rope. It was heartbreaking, that moment of getting pushed away from our home, where we’d lived for almost a year.

We worked hard to make it a home. We gave up everything to be there. And then we got pushed out. It felt like I was being robbed.

The night before, a lot of people burned their camps because they would rather have it burned than taken by the ranchers. When the police cleared everybody out, they let all the ranchers come in and take whatever they wanted. We had sheep and pigs there; they just took them. We were like, “We worked hard for this. We aren’t gonna let anybody just take it.” So a lot of people just burned their camps, burned the kitchens. Everything was on fire and the snow was coming down. Some of the snow was actually ash. It was like Armageddon, like the world had ended, and everything was in chaos.

Today, when I hear airplanes, I get flashbacks. Or when I hear shouting or police sirens—I know I’m not doing anything wrong, but I still get scared. Like someone’s going to shoot me or something. It’s hard to trust these people with badges. You come home, and you see the police. And it’s just like, How I can trust them to protect me? I can’t say I’ve come out of it perfect, but I have come out of it stronger. What worse will I go through?

We spent so much time birthing the movement, seeing it grow into something that impacted millions of people, that echoed across the world.

How could they do that to us? After camp at Standing Rock, we came back here, to Cheyenne River. I found out I was two months pregnant. I was just . . . mind blown. And I didn’t have that much support. The baby’s dad left me for some other woman. And he didn’t want anything to do with me.

And dealing with the fact that we lost the camp was heartbreaking for me. It was a lot to deal with. I fell into a depression. I didn’t want to go anywhere. I just stayed in my room for like two months. I wasn’t happy—at all.

Today, when I hear airplanes, I get flashbacks. Or when I hear shouting or police sirens—I know I’m not doing anything wrong, but I still get scared.

I didn’t really know much about being pregnant then. I didn’t know that your emotions affect your child, and I ended up losing my son. The miscarriage was probably worse than getting maced, the pain that I went through. It was really hard. I buried him at his dad’s grandfather’s place out in the west end, right next to the creek. When I lost him, it kind of snapped me out of my depression. He became my motivation. I have something to protect. Now my son’s buried by the river. Now it’s my turn to fight for him. I attended ceremonies and I laid him to rest. I vowed to him that he’s going to be safe, that no oil was going to touch him. He’s in the ground now, so it’s my duty to protect the earth.

I know I’ll see him again. When I went to ceremony, he said he’ll come back to me when I’m ready and when it’s safe for him, when his future is secure. I don’t want to have a kid knowing I can’t give him fresh water. I want to make sure that my children have a good future.

And when they do get here, I want to be able to tell them, “I fought hard for you. I fought for your water. I fought to make sure you have a good life.” I want them to be proud of their mom. So that’s something that really got me out of blaming myself for the miscarriage. I didn’t get over it. But the pain I still feel from it fuels my passion to keep going. He has become my inspiration.

Sometimes I wonder what life would be like if he was still here. He would’ve been one year old. It’s still hard for me to adjust. I never asked to be a leader, or to be a mentor.

But I’ve come to understand that even if I don’t want it, I can’t walk away from it. While I was going into a depression when I came back from Standing Rock, Joye Brown sat me down. She was like, “A lot of young women, a lot of young men saw you speak. What would they do if they’d got inspired by you and then one day looked on Facebook, or on the news, and they see that you’re gone, that you killed yourself?

You’re just giving that choice more power, telling them that suicide is okay. That person who did that amazing thing gave up, so I can give up.” She said it would plant a seed of hopelessness inside of them. I heard that, and I was like, Dang. That’s kind of right. When you’re in grief, you don’t think about who it’s going to affect. But it has a domino effect. Your grief doesn’t go away when you die.

It just transfers into someone else, someone else carries it. I didn’t want to do that. So I started trying to help my friends with suicide prevention. I’d say, “Whenever you feel sad, come talk to me. Talk to someone. Go for a walk. Ask me to go for a walk. I’ll listen to you.”

We met a lot of people at Standing Rock who became family. And when we call upon them, they’re going to come. They’re just waiting. I hope it doesn’t come to that.

South Dakota doesn’t want what happened at Standing Rock to happen here. KXL keeps sending letters to our tribal chairman, Harold Frazier, like, “What can we do to make sure that this doesn’t turn hostile?” I loved what our tribal chairman said: “Just don’t build it. ●

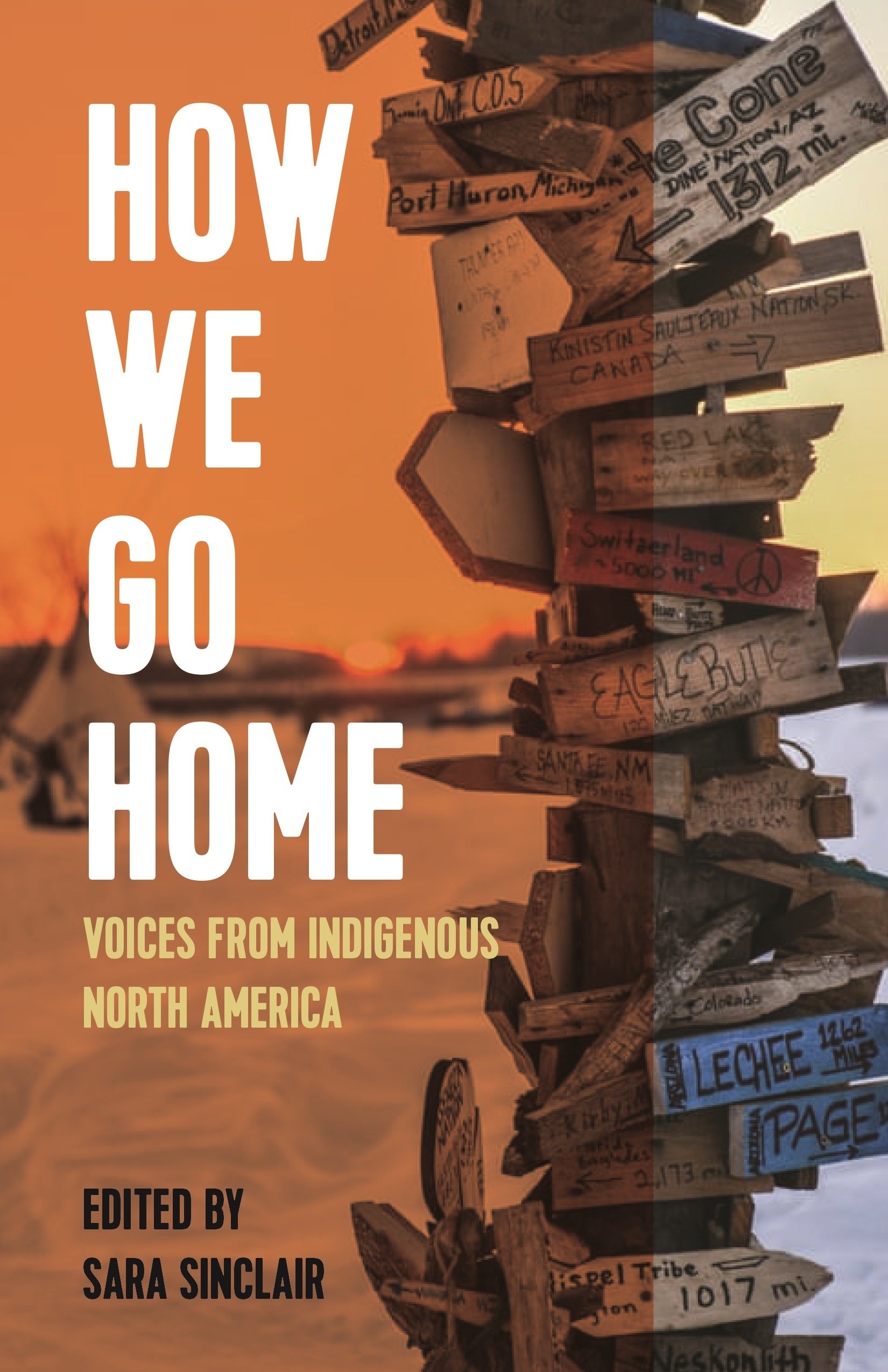

Excerpted from How We Go Home: Voices from Indigenous North America, eds. Sara Sinclair (Haymarket Books, 2020).