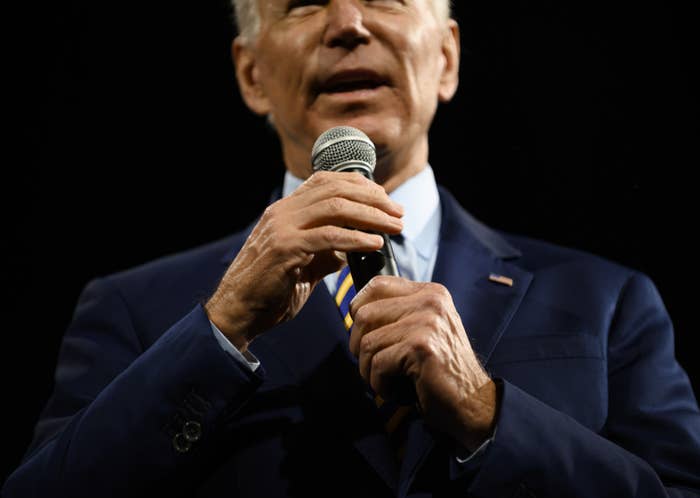

DES MOINES — Joe Biden’s fight for the soul of America often feels like a fight for the soul of Joe Biden.

His four-day swing through Iowa began with a confident rebuke of President Donald Trump’s racist rhetoric. The Wednesday speech in Burlington was timely, given the domestic terrorism days earlier in El Paso, Texas, but also consistent with the themes Biden has campaigned on for months.

The next night, Biden’s gravitas gave way to rambling. At an Asian & Latino Coalition event in Des Moines, the former vice president twice ignored a fearless moderator’s requests that he shorten his answers. When a teen asked how he would protect her generation from school shootings, Biden alternated between empathetic and defensive. He talked at her: hunched over, palms down flat on the table in front of her as they locked eyes. He wanted her to know that the survivors of last year’s school shooting in Parkland, Florida, had come to visit him — and, in Biden’s telling, only him.

“Me,” he said. “Nobody else. Me. I met with them. I met with their families.”

It can be easy to miss and hard to put your finger on, especially when Biden leads the Democratic presidential field in polling and puts on his aviator-clad frontrunner’s face. But Biden presents with a vibe of doubt. He can come across as a candidate who’s worried that he’s running out of time — and that he’s wasting yours. And he’s not always sure how to make the most of it.

Sometimes Biden talks too much, like he did at the Asian & Latino Coalition forum and another event last week where he shouted over music meant to play him offstage. He has a tendency to step on his own applause lines and quiet the cheers, as if he needs to reassure his crowds that what they’re clapping for is legit. “Not a joke,” Biden likes to say.

Sometimes Biden doesn’t talk enough. He tells crowds about the plans he has, but he insists that sharing all of the details would keep them there longer than they would like. He loves to reminisce about his eight years in the Obama administration, but not so much about old Senate votes or friendships with segregationists. When responding to Sen. Kamala Harris’s attack on those grounds at a June debate, Biden abruptly finished his rebuttal with seconds to spare and a line some heard with a dual meaning: “Anyway, my time is up.”

And sometimes Biden says the wrong thing. Many dispatches from the Iowa trip dwelled on his verbal blunders here.

He botched a line from his stump speech at the state fair. (“We choose truth over facts.”) He told the Asian & Latino Coalition audience that “poor kids are just as bright and just as talented as white kids” before catching himself and adding “wealthy kids, black kids, Asian kids.” He also blanked for a second when he seemed to confuse former British prime ministers Margaret Thatcher and Theresa May. Two days later, at a forum on gun control, he talked about Parkland again and recalled meeting with the survivors when he was vice president. But the high school shooting happened more than a year after Biden left office. His staff later explained he had meant the 2012 Sandy Hook elementary school shooting in Connecticut.

“Wouldn’t it be nice,” his deputy campaign manager tweeted, “to have a president who consoles Americans in their time of need so often that he sometimes mistakes the timing?”

The slipups make it convenient to question if Biden, at 76, is up for the job. Trump, 73, has jumped on them. “Does anybody really believe he is mentally fit to be president?” Trump asked Sunday.

But Biden has been making mistakes like these — gaffes, as the political press judges them — for years. The Iowa trip got at a deeper and more existential challenge. Gaffes used to be part of his charm for a certain type of Democrat. Now they’re something that, win or lose, could affect how history remembers him. They can be a bother at a time Biden doesn’t want to be a bother.

“Anybody that does a lot of public speaking, sometimes the words kind of get muddled and they don’t come out just right,” Tim Winter, chair of the Boone County Democratic Party, said after hosting an error-free Biden speech the morning after the “poor kids” remark. “Your heart is good. You mean to say the right thing. Sometimes it just comes out wrong.”

Biden’s case to be president is wrapped in the notion that the only way to move past Trump, and to render the racism and bigotry Trump’s presidency has fostered an aberration, is to first move back to the Obama–Biden years. “Third term!” one supporter, waiting to snap a Biden selfie with a disposable camera, shouted during a Friday afternoon rally at a public park in Clear Lake, Iowa.

Yet even among Iowans who admire Biden and might be inclined to caucus for him when primary season begins in February, there’s a sense his argument and his approach might not be enough to beat candidates who are fresher or more progressive. Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana, and Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren drew louder cheers and larger ovations at the Iowa Democratic Wing Ding, a big party dinner that brought more than 20 presidential contenders to Clear Lake’s historic Surf Ballroom. (It’s known for hosting the last performances of Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper before their fatal plane crash.)

“I think some folks thought it would just be a cakewalk for him,” J.D. Scholten, an influential Iowa Democrat and congressional candidate, said of Biden in an interview with BuzzFeed News. “I think he’s going to have to earn it like every other candidate. More people know him, so there’s that advantage. But ultimately their campaign is going to have to do the hard work.”

Biden didn’t help himself at the Wing Ding by smothering his few crowd-pleasing lines in what was the last of more than two dozen speeches the audience had heard over three hours.

“I’m not saying that for applause,” he interjected when they clapped for his assertion that reelecting Trump would represent an “existential threat” to the country. He quickly segued into a dark riff about the Ku Klux Klan and then rushed past perhaps his most poignant observation: “There’s no evidence that the presidency has awakened his conscience in any conscious way.”

When his walk-off music (Bruce Springsteen’s “We Take Care of Our Own”) began playing to signal that his allotted five minutes had expired, several moments after a person in front of the stage silently held up a sign that said "STOP," Biden seemed surprised. After a brief pause, he began shouting a bunch of the phrases he often ends with in his traditional, extended stump speech.

To the extent that Biden’s age comes up as an issue with voters at his events, it’s less a concern about his ability and more the appeal they see in younger candidates such as Buttigieg.

“No!” Karen Hesser, a 71-year-old retired teacher, replied when asked if Biden’s age worried her after she heard him speak outside for 20 minutes — short for Biden, and with the aid of a teleprompter and notes — under a blazing sun Friday in Boone. “Look at me! No!”

Biden crowds trend elderly. As sound technicians investigated the cause of a janky microphone at the Asian & Latino Coalition event, they jokingly blamed interference from the hearing aids in the room. The teen who worried about school shootings and the moderator who pleaded for brevity — who conspicuously collected her purse and left in the middle of Biden’s final answer only to return minutes later and find him still going — were among the youngest there. At the pre–Wing Ding rally, a band played Tom Petty and Creedence Clearwater Revival covers as a few dozen Biden supporters, a slightly younger after-work crowd, waited for Biden to arrive.

Biden crowds also trend smaller than those of his rivals. His Thursday visit to the Iowa State Fair makes for tough comparisons, given that it was a weekday, and the fair’s opening day, but Biden playfully wondered whether any other candidate could draw as many people as he had. By the end of the weekend, several others had. Besides, Biden spent most of his time at the fair with the reporters who swarmed him before and after his half hour at the Des Moines Register Political Soapbox.

Reporters followed Biden as he signed autographs and took selfies along the fair’s Grand Concourse. After a few minutes, he asked the group to move into a nearby beer pavilion. He said he was worried about being in the way. When he was done signing, his team led him away. Reporters chased him again, firing off repeated questions about whether he considered himself the frontrunner — “Is that target still on my back?” he replied — and why, unlike some other Democrats in the race, he has been unwilling to call Trump a white supremacist.

It was clear the latter question annoyed Biden, who cites Trump’s mollifying of white supremacists after the violence in Charlottesville two years ago as a reason he ran for president. No candidate has made Trump’s rhetoric the rationale for their campaign the way Biden has. He has called Trump a white supremacist in so many words, just not in those precise words.

“You just want me to say the words so I sound like everybody else,” Biden snapped. “I’m not everybody else. I’m Joe Biden. I’ve always been who I am. I’m staying that way.”