"Develop a thicker skin." It's a phrase I've heard a lot over the years (as recently as a few days ago), and for a long time I took it to heart and hoped I would develop the kind of calluses that these people were talking about. I'm a woman who's had an internet presence for a little more than a decade now. Which means that for the last 10 years I've been told that I'm a stupid cunt and that I should do the world a favor and kill myself fairly often, mostly by anonymous strangers. If you're shocked, you're likely not a woman. Or maybe you're not online much, or you've never had a controversial opinion in your life; maybe your "corgis eating ice cream cones" Pinterest board is the extent of your ventures into social media, and if so, god bless. Personally, I've come to expect online attacks and threats; I've dealt with them for so long that they hardly register. I accept them in the same way that I've come to accept that smelling piss and garbage is an inescapable part of living in New York, which I also do.

But as it keeps happening, I start to wonder whether the problem is really mine.

This summer, the week that my first novel, Friendship, was being published, a longtime "lit blogger" named Ed Champion published an 11,000-word attack that crossed every kind of line, including imagery of sexualized violence, several photographs of me, and a reference to my "slimy passage."

I was about to embark on a book tour, and concerned friends and co-workers in publishing quickly informed me that Champion had a reputation for showing up at authors' events and creating disturbances. I tweeted about how upset I was, but this just seemed to fan the flames, and once I realized what was happening, I stopped. At a time when I'd had most cause to hope that the conversation about me might finally shift to my writing itself, it was instead, once again, about my internet presence, me as a "lightning rod" for criticism, and the question of whether or not I deserved or even courted that kind of attention. Being silent didn't make me feel better, though; I lasted about a day off Twitter, then started participating in the conversation again.

Many people, it turned out, had read those 11,000 words and didn't understand what the fuss was. This was "just a book review." A very bad review, but still. I should learn to take criticism more gracefully. I should develop a thicker skin.

Or better yet: Just ignore it! (As Salon senior writer Laura Miller advised the other day.) This is, of course, what you're supposed to do with actual book reviews. Authors are supposed to say, "Oh, I don't read reviews" in the same tone of voice that people use to describe having given up TV or refined carbohydrates. But I always read reviews; I can't help it, and I don't feel guilty about it, either. I've never seen writing as something that takes place in a hermetic aerie far above the world; I like to have a conversation about my own writing and other people's, and most of that conversation takes place online. I'm interested in general in how people write about books, and of course I'm even more interested when those books are mine.

And one thing I've noticed, reading reviews not just of my own books but of the books I sell via Emily Books, is that a lot of female authors are subject to the same treatment I've gotten. These authors are reviewed personally alongside their books, in a way that rarely happens to men. The author Jennifer Weiner tweeted several examples the other day, including "reviews" of herself, Fifty Shades of Grey author E.L. James, and one of my own book: In the New York Times, lead book critic Michiko Kakutani took three paragraphs even to get around to mentioning my book, and on the way there, she quoted — somewhat extensively! — from anonymous comments left on a 2010 essay that I wrote. In a review of, supposedly, my novel.

In a climate where no one — no editor, no reader, no publicist — steps in and says to the lead book critic of the New York Times, "Wait a minute, isn't that enormously and obviously fucked up?" it's not surprising that people can't tell the difference between Champion's unhinged ramblings and a "book review." I'm offended on my own behalf, of course. (Duh!) But I'm also worried about girls and women reading this kind of thing and mistaking it for a fixed condition of a literary culture they're trying to find a place in.

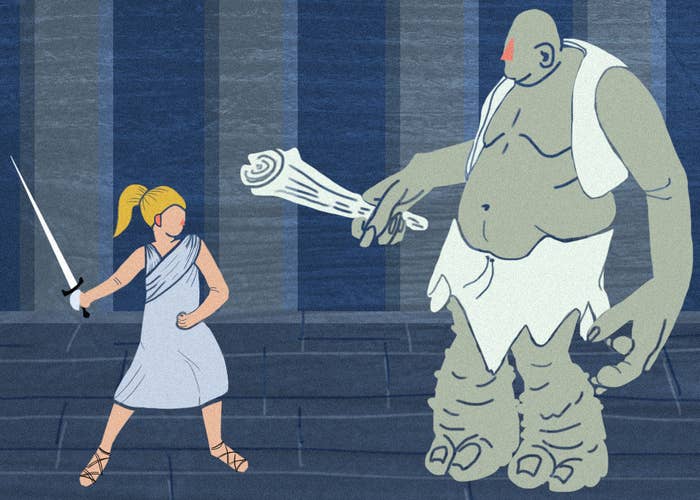

Even if Champion's rant had been a "book review," which it wasn't, it's not my job to ignore it. I'd go so far as to say that the people who tell women to "just ignore" gendered criticism, bullying, and harassment — which I'm fine with lumping together, because they're all components of a system that works together to repress women's work — are asking women to collaborate in their own silencing. I'm not going to ignore it; I'm not even going to try. If "feeding the trolls" provokes or encourages them in the short term, I don't really give a fuck. In the long term, with sustained resistance, it's the only way to create the impression that something has to change. If there's anything the last 10 years have taught me, it's that telling the truth isn't always fun, but it's the only way to change anything.