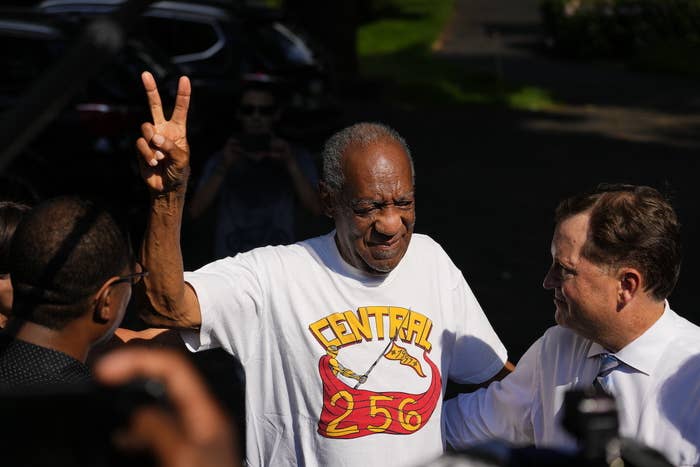

Bill Cosby walked out of prison on Wednesday afternoon, two years into what was supposed to be a sentence of three to 10 years after he was found guilty of raping Andrea Constand at his home in 2004. Hours earlier, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court had tossed out the conviction.

What happened?

A majority of the state justices concluded that Cosby’s constitutional rights had been violated when local prosecutors in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, charged him in 2015. The problem with that criminal case, the court found, was that a previous district attorney had announced a decade earlier that Cosby wouldn’t face prosecution. That announcement triggered a series of events that included Cosby providing incriminating information against himself in a civil lawsuit, which eventually became part of the criminal prosecution he was under the impression would never happen.

It’s an extraordinary situation that, as the court itself noted in Wednesday’s decision, was without precedent. The problem wasn’t just that then–Montgomery County district attorney Bruce Castor had made an unusual public commitment outside the normal process for an immunity agreement. It also wasn’t just that a later district attorney went back on Castor’s public pledge. The court found that Cosby’s decision to rely on Castor’s statement and incriminate himself in the civil case, and to then have those statements used against him, ran so far afoul of his due process rights that the only way to fix it was to throw out the entire prosecution.

“We do not dispute that this remedy is both severe and rare. But it is warranted here, indeed compelled,” Justice David Wecht wrote for the majority. “[S]ociety holds a strong interest in the prosecution of crimes. It is also true that no such interest, however important, ever can eclipse society’s interest in ensuring that the constitutional rights of the people are vindicated.”

The wheels had been set in motion in 2005, when Castor first learned about Constand’s allegations against Cosby: that a year earlier, the actor had given her pills that caused her to become incapacitated and then sexually assaulted her. But Castor ultimately wasn’t convinced that his office could prove the case in court given that Constand waited a year to file her complaint with law enforcement. There also was no forensic evidence, and Castor believed Constand’s recollections would be less precise.

Castor told Cosby’s team and, importantly, stated in a February 2005 press release that he would not bring criminal charges related to Constand’s allegation. Castor — who more recently defended former president Donald Trump in his February impeachment trial — later testified that his intent was to try to still help Constand get justice. By taking a criminal prosecution off the table, Castor believed that would prevent Cosby from invoking his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination in Constand’s civil lawsuit.

Fast-forward a decade. In 2015, when dozens of women began making similar accusations against Cosby, documents in Constand’s civil case were unsealed in response to a media request. Then–district attorney Risa Vetri Ferman then reopened the criminal investigation that her predecessor had closed.

Castor wrote to Ferman, warning her about his public promise to Cosby, but she chose to press on. Her successor, Kevin Steele, formally charged Cosby in December 2015 with three counts of aggravated assault.

A jury eventually found Cosby guilty in April 2018. He was sentenced several months later, and in addition to the prison term, he was required to register as a sexual predator.

Castor would later say that he had intended to block local prosecutors from bringing criminal charges against Cosby related to Constand’s allegations at any point in the future. But he did not get Constand’s consent to make this decision, or even communicate his promise to Constand or her lawyers. She learned about it from a reporter.

He also didn’t negotiate a formal immunity agreement with Cosby and present it to a judge to get an official order that would be legally binding on the district attorney’s office going forward. Instead, as the Pennsylvania Supreme Court described it, Castor’s statement was “a unilateral exercise of prosecutorial discretion.” Lower courts that considered Cosby’s case found that this sequence of events cut against Cosby’s argument that it was reasonable for him to rely on Castor’s statement when he decided to testify against his own interests.

Cosby ended up sitting for four depositions in Constand’s civil lawsuit, during which he confessed to several incriminating acts, including providing quaaludes to other women he wanted to have sex with, though he insisted he just gave Constand Benadryl. Eventually, Constand settled the suit for $3.38 million.

But the state Supreme Court had a different interpretation of the legal heft of Castor’s announcement, even if there hadn’t been a formal immunity agreement.

“[W]e hold that, when a prosecutor makes an unconditional promise of non-prosecution, and when the defendant relies upon that guarantee to the detriment of his constitutional right not to testify, the principle of fundamental fairness that undergirds due process of law in our criminal justice system demands that the promise be enforced,” Wecht wrote.

Two former prosecutors who reviewed the court’s decision told BuzzFeed News it is very common for prosecutors to tell defense attorneys that they don’t plan to pursue charges. But normally, they said, officials don’t put out press releases about it.

“I’d been a prosecutor for more than 40 years and certainly I would periodically tell or even write to a defense lawyer saying we would decline to prosecute right now,” Michael Levy, the former assistant US attorney in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania and a current law professor at the University of Pennsylvania, said. “I would never have thought of that as meaning no matter what happened we would never go ahead” with the criminal case.

“What makes this highly unusual is the public nature of this,” Shan Wu, a former federal prosecutor, added. “Then there’s the reliance by Cosby on that to say that, OK, well if I’m not facing any danger, I can testify in the civil case.’”

But Wu also questioned the decision by Cosby’s lawyers to let him testify at all, notwithstanding Castor’s press release.

“Any time you have a person who has been charged or accused formally, it’s very, very risky to let them say anything ever,” he said. “If I were Cosby's attorney back then, I would have fought tooth and nail against him being deposed.”

The state supreme court said in their opinion that, despite the deposition testimony being a bad idea, it was reasonable for Cosby to rely on the advice of his lawyers and the then-district attorney.

“We cannot deem it unreasonable to rely upon the advice of one’s attorneys,” Wecht wrote. “A criminal defendant confronts a number of important decisions that may result in severe consequences to that defendant if, and when, they are made without a full understanding of the intricacies and nuances of the ever-changing criminal law.”

The court’s decision wasn’t unanimous. Justice Thomas Saylor wrote that he did not agree with the majority that Castor’s press release was an “unconditional promise.” He said he believed the release was a “conventional public announcement” by someone in a temporary, elected position that would “in no way be binding upon his own future decision-making processes, let alone those of his successor.”

Justice Kevin Dougherty, joined by Chief Justice Max Baer, wrote separately to say that he agreed with the majority that “due process does not permit the government to engage in this type of coercive bait-and-switch.” But he disagreed with tossing out the case entirely, writing that the appropriate outcome was a new trial where any evidence from Cosby’s depositions was suppressed.

Hours after the decision was released, Steele, Montgomery County’s current district attorney, said in a statement that it should not deter victims of sexual assault from seeking justice.

Cosby "now goes free on a procedural issue that is irrelevant to the facts of the crime,” Steele said. "Prosecutors in my office will continue to follow the evidence wherever and to whomever it leads. We still believe that no one is above the law — including those who are rich, famous and powerful.”

But in a statement to BuzzFeed News, Jennifer Bonjean, Cosby’s current attorney, said that "at the end of the day, there has to be a fair process, prosecutors have to live up to their word."

"We cannot change decades in history of our treatment of women on the shoulders of one man, or two men, which is what seems to be happening,” she said. “There's a lot of work that needs to be done. And we, we can't undo the past simply by cheating and breaking the rules and disregarding our cherished constitutional principles because it makes us feel good."