On the day Jathan Laverty turned 26, he was working at a Columbus, Ohio, coffee shop and freelancing as a corporate event technician, hoping to get a foot in the door of the event planning industry. This birthday turned that search for a full-time job into something urgent.

Laverty has Type 1 diabetes, and as of that day in 2017, he was no longer eligible for coverage under his parents’ health insurance. He found himself needing medication to live that he could not afford.

“It’s a human necessity for me,” Laverty, now 28, told BuzzFeed News. “It’s my life or death every time I do or don’t take insulin.”

Laverty faces a health care problem unique to many millennials with Type 1 diabetes who’ve been booted off their parents’ stable health insurance. The price of insulin, the drug that keeps them alive, tripled in the US from 2002 to 2013 — and a recent study found that, from 2012 to 2016, its average annual cost increased from $3,200 to $5,900.

That’s an impossible price tag for a generation still feeling the effects of the 2008 financial crisis and saddled with massive student loan debt and increasing housing costs. Studies show that US millennials are far worse off financially than previous generations, with an average net worth below $8,000.

The result is that these young adults are rationing, stockpiling, and turning to the black market for the medication they need to stay alive — incredibly risky and desperate measures that could result in long-term harm or death.

About 1.25 million Americans have Type 1 diabetes, a disorder in which the immune system attacks the pancreas and interferes with the body’s ability to absorb energy from food.

People with Type 1 diabetes are dependent on multiple types of insulin to survive because the disease shuts down the pancreas’s ability to produce the chemical, which regulates the amount of sugar in the blood. Without insulin, cells cannot absorb sugar, and the body is forced to rapidly break down fat cells to use as a backup fuel source. This dehydrates the body, turns the blood acidic, and leads to a life-threatening complication called diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

Most people with Type 1 diabetes take at least two types of insulin: a long-acting type, taken daily, that constantly releases insulin, and a short-acting or rapid-acting type, taken either before or after eating. The amount of insulin a person with Type 1 diabetes needs varies dramatically depending on age, weight, food eaten, exercise, illness, stress, and, for women, whether they are menstruating or ovulating.

In fact, many endocrinologists will overprescribe insulin so that patients have enough for emergency situations.

All that medication is pricey. Laverty said that in 2017, his insulin cost him approximately $950 a month without his parents’ insurance coverage. So he began to ration. He gave himself only what he could afford to buy, the bare minimum he needed to function.

“I was taking half of my medication that I needed to be taking,” he said.

Laverty began skipping meals so he wouldn’t have to use a dose of his fast-acting insulin, and he lowered the amount of insulin in every injection he gave himself. The effects were immediate. His energy levels dropped, leaving him irritable and fatigued and in a constant state of discomfort. He couldn’t sleep, he was always thirsty, and he constantly had to urinate.

“It definitely affected my ability to function,” he said. He lived like this for four months until he found full-time employment at a company that offered full medical benefits.

This sort of rationing can have serious long-term effects for people with Type 1 diabetes, Simeon Taylor, a University of Maryland School of Medicine diabetes researcher and professor, told BuzzFeed News.

“You can probably avoid rapid death,” he said. “But you open yourself up to long-term complications like blindness, kidney failure, amputations. If you’re not treating yourself optimally, you’re also at greater risk for shorter-term crises.”

For Nicole Smith-Holt’s son Alec Smith, the situation was deadly. Smith died of DKA in 2017, one month after turning 26 and being kicked off his mother’s insurance. He couldn’t afford insulin and had been rationing what little he had left.

In August, Smith-Holt testified before the US Senate about her son’s story and what she called the “crisis of pharmaceutical drug prices.” Smith-Holt told BuzzFeed News that she has heard from “far too many” people with stories like her son’s. A December study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association revealed that 1 in 4 people with diabetes have rationed their insulin because of high costs.

“On a daily basis I’m contacted by people,” Smith-Holt said. “By both parents of young adults or young adults themselves. They’re fearful of what’s going to happen. They’re dreading turning 26 years old.”

Aging out of parental health insurance has always been an issue for young Americans with chronic health conditions. But ever since the 2010 Affordable Care Act allowed young adults to remain on their parents’ insurance until the age of 26, there has been a universal deadline.

Louis Philipson, director of the University of Chicago Kovler Diabetes Center, told BuzzFeed News that he sees many young adult patients with Type 1 diabetes living in fear of this deadline.

“They’re on their parents’ insurance now, but some are in the gig economy, moving from one job to the next as they start their lives. They may not have a job with insurance that covers their insulin, or their job may have zero insurance, or it’s a job that’s underinsured with high deductibles,” he said.

The rising cost of deductibles — the annual amount that a patient must pay out of pocket before their insurance plan begins to pay — is an issue for all Americans. A comprehensive nationwide analysis published in May showed that deductibles in job-sponsored insurance plans have quadrupled in the past 12 years and average more than $1,300. High-deductible plans are also common for those who are insured through the state exchanges established under the ACA, and these deductibles can be even higher than those in job-sponsored plans. In 2018, the average deductible for the most popular type of plan on the exchange was nearly $4,000. The cost of the deductible is in addition to the cost of the monthly premium payment.

Because being kicked off your parents’ insurance is considered a “qualifying life event,” young adults are given a 60-day special enrollment period after their birthday to sign up for new insurance. But some young adults with Type 1 diabetes find it difficult to afford their medicine even with government-sponsored insurance.

“I looked into it,” Jathan Laverty said about going on government insurance. “But it was going to be so stupid expensive that it wasn’t worth it.”

He said that the plans he was able to find on the exchange had such high deductibles that he felt he would likely find a full-time job with benefits before he met his deductible. In the interim, he would be paying list price for insulin during that in-between period with or without government insurance.

“The first month [of medication] alone could be $1,000 or even more,” Philipson said. “It breaks budgets, it forces people into untenable situations: You have to choose between rent and insulin.

“Turning 26 — there’s a looming fear that you’ll be spending $500 a month, $5,000 to $6,000 a year, to stay alive,” Philipson said. “This isn’t an option. Type 1 diabetes is a fatal disease if you don’t have insulin.”

The deadline is approaching for Allie Marotta, a 25-year-old living in Brooklyn.

“I’m a freelance theater person; there’s no insurance there,” Marotta told BuzzFeed News.

Marotta is planning to either get a job with good health insurance or buy insurance through the government. However, she is “preparing to be uninsured for a period of time, since both of those things take time.” So with the help of her endocrinologist, she has begun stockpiling insulin.

Marotta’s doctor has been giving her her insulin samples from the supply that endocrinology offices keep on hand for emergencies and to teach newly diagnosed patients how to dose themselves. Marotta said that her endocrinologist is also prescribing her extra insulin.

“She’s like, ‘Let’s get you as well-stocked as you can for now so you can bide that time a little bit better,’” Marotta said.

Marotta is also trying to get her current insurance provider to approve her for a continuous glucose monitor, a device implanted under the skin that constantly reads a person’s blood sugar levels.

“I had one back in college and it’s really great,” she said. “I don’t love having something attached to me all the time, but I want to go back on one so I can have my [blood sugar] really perfect, knowing as much as I can about my trends to be more prepared for this period of uncertainty.”

Even though she currently has insurance, Marotta still regularly rations insulin. She regularly buys only one of the two types she needs, because she can’t afford the copays for her multiple required medications, doctor’s appointments, and a battery of tests that accompany each visit to her endocrinologist.

“I’ll pick up my short-acting before I pick up my long-acting because at least you can do emergency coverage,” she said. “If you’re only going to have one, it makes sense to do the short one. It’s just not ideal because you don’t have that baseline [of insulin], so the slightest thing can affect you and your blood sugar goes up.”

It’s dicey, but Marotta said she’s spending close to half her income on student loans and rent. She doesn’t have a choice.

“For me, rationing is literally just because I don’t have the $20 to pick it up today,” she said.

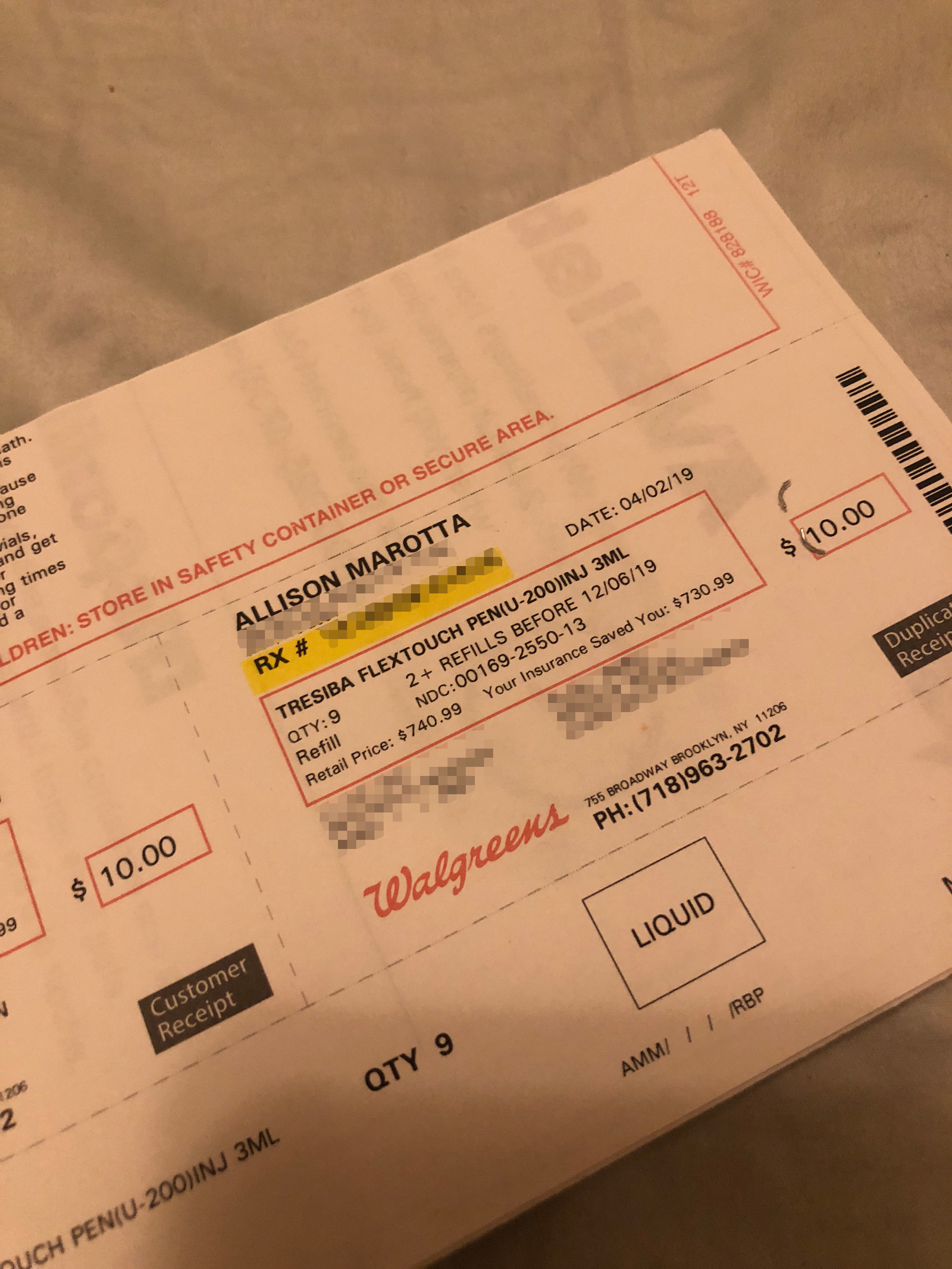

The list price for a monthly supply of Marotta’s long-acting insulin, according to a receipt she provided to BuzzFeed News, is $740.99. Her current copay is $10.

People with Type 1 diabetes also need to pay for multiple expensive supplies to help control their disease. Patients who can’t afford them cut corners by not regularly testing their blood sugar levels, relying instead on their body’s response to determine how much insulin they need. They also reuse one-time-use medical supplies, such as lancets that prick fingers to test blood sugar and needles to inject insulin, despite the risk of infection.

“That’s a huge part of rationing that people don’t talk about, and a lot of people do it,” Marotta said.

Jathan Laverty said that although he is no longer forced to ration his insulin, he regularly rations supplies to keep costs down. He said that he often reuses a lancet “for weeks or months,” until it’s so dull that it no longer breaks the skin.

“This becomes increasingly more unpleasant and leaves a larger hole, but it saves me a lot of money,” he said.

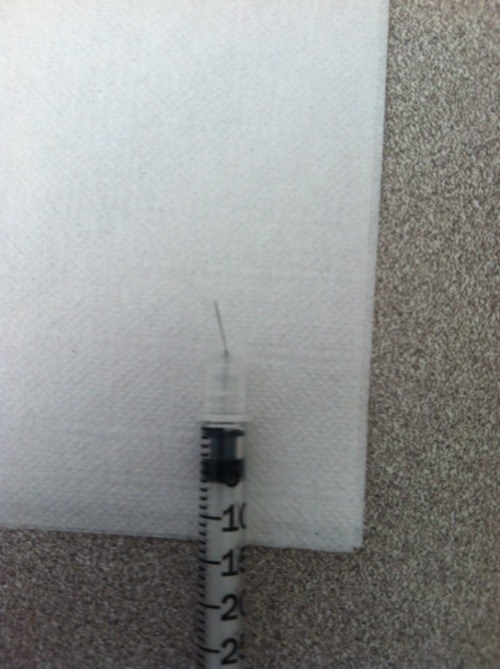

He added that he is supposed to use a new needle tip for his insulin pen each time but limits himself to one per day because it got “crazy expensive.” He estimated that he doses himself between five and eight times a day, with each dose becoming more painful. Before he switched to pens, he would reuse syringes and needles to inject himself with insulin. He shared a photo with BuzzFeed News of a used needle that bent and broke off inside his body during a regular injection.

Sometimes, because of circumstances beyond their control, people with Type 1 diabetes are forced to turn to risky options. In 2017, Julia Wyrzuc, 24, of Linden, New Jersey, was left to scramble after a clerical error left her family uninsured for five months.

She had a small surplus of insulin stored up and was also able to obtain samples from a family friend who worked at an endocrinology office. However, as it became clear that resolving the insurance issue would take months, not weeks, she had to find a more permanent solution. In July 2017, she turned to the black market.

She purchased 10 vials of insulin for $1,000 “from a guy who had really good insurance,” she said. It wasn’t a “terrible” price and was cheaper than what Wyrzuc would have paid over the counter. She was using insulin from this stockpile when, a few months later, she went into “severe DKA.”

“I’d never felt that terrible in my life,” Wyrzuc said. “I was throwing up for 12 hours; I couldn’t even sip water.”

Wyrzuc was hospitalized, spending five days in the intensive care unit. Her doctors speculated that she had taken a “bad batch” of insulin that had possibly overheated at some point.

Fortunately, her parents had resolved the insurance issue “literally two weeks” before this happened, and Wyrzuc was able to resume her regular treatment regimen.

Even when young patients with diabetes secure their own health insurance, they can face problems.

Hannah Sumner, 26, of Soperton, Georgia, voluntarily switched off her parents’ insurance before she was required to, which she described as “the biggest mistake of her life.”

“I got a job that offered insurance and I wanted to do it on my own,” she told BuzzFeed News. “I have a 6-year-old daughter. I was trying to be more of an adult.”

Her plan through the bank where she works has great coverage — for everything except diabetes. Her insurance company also recently stopped covering her brand of insulin, forcing her to switch to a brand it deemed equivalent. The new insulin, she said, makes her sick, but she cannot afford to switch back to her old one and has to cope with the symptoms.

Sumner said her pharmacist allows her to put the bulk of her deductible, which she said is around $225 to $250, on a charge account at the start of the year so she can afford her insulin. She pays the account monthly, but there are times her finances are stretched so thin, she can’t even afford the copayment.

“There are times of the month when I might not have $50,” she said.

On those months, her pharmacist, an “amazing” family friend who has known her since she was a baby, lets her add her copayment to her charge account as well.

Even with this “incredibly lucky” arrangement with her pharmacist, Sumner said she has rationed in the past for financial reasons and is currently rationing so that she can go to her job without feeling sick from her new insulin.

“I’m not going to be able to work one day because of this disease, and I want to work now,” she said.

Sumner’s disease weighs heavily on her, especially as a mother.

“Of course you have that fear of getting sick and dying,” she said. “I’ve taught my daughter how to handle that, how to call 911.”

Many of those who spoke to BuzzFeed News said that, because of the cost of insulin, they have been compelled to pursue careers that offer job security and extensive health benefits coverage, such as nursing.

One teenager, Brooke Raper of Houston, told BuzzFeed News her Type 1 diabetes is a factor she’s forced to consider as she decides what she wants to do with her life. She feels very pressured to be financially successful.

“I’d ideally like to pursue a creative career, but that might not have stable insurance — I have to have a stable income,” she said. “Whenever the cost [of insulin] will affect me, I know it’s going to be a heavy burden.”

Jathan Laverty said that learning he had Type 1 diabetes at age 21 forced him to change his entire life. He went to school for theatrical lighting design and dreamed of one day working on a Broadway tour. But he changed his plan and now works in corporate events for the steady insurance coverage.

“I realized I had to have health insurance to stay alive, that I had to change my career so that I have health insurance. A roadie doesn’t always have that,” he said.

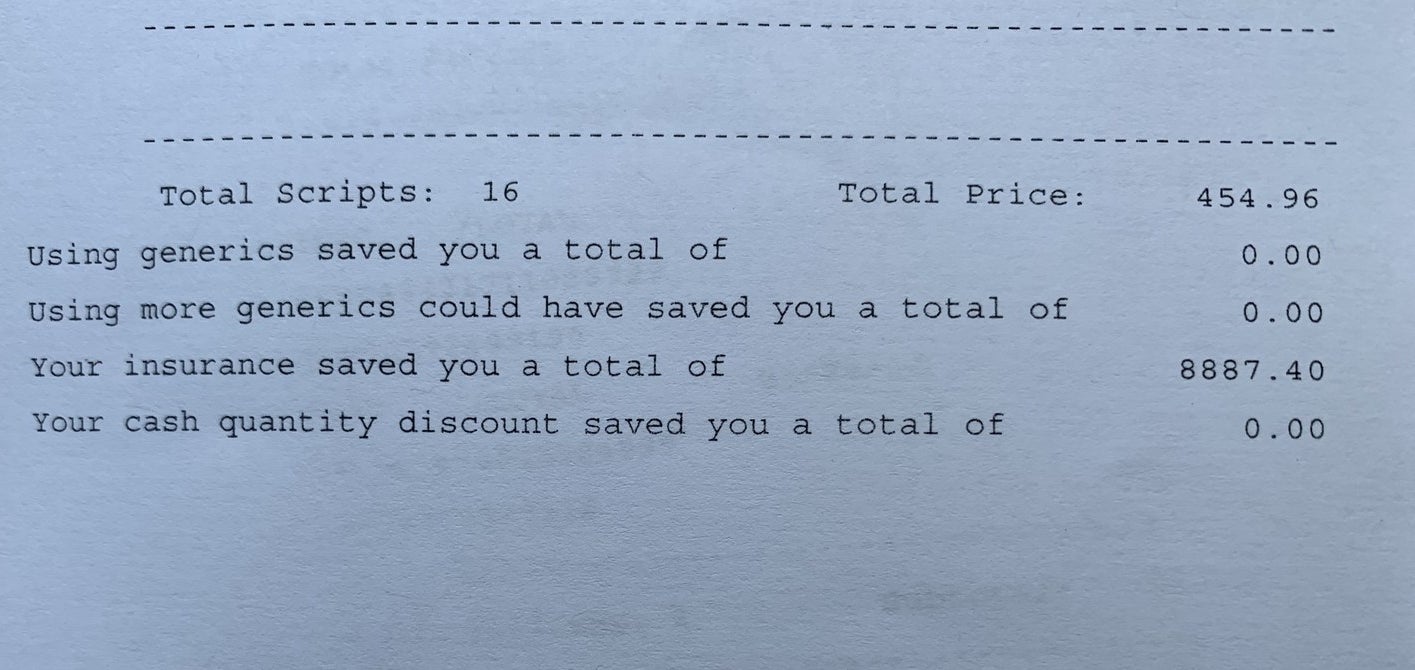

Without insurance, Laverty would have paid nearly $8,900 for his insulin in 2018, according to receipts he provided to BuzzFeed News. Including his $1,200 deductible, his out-of-pocket cost for his yearly insulin was $1,654.96.

The people with Type 1 diabetes BuzzFeed News spoke to said no matter how much they try to be smart about managing their disease, no amount of planning can ease the looming feeling of uncertainty that comes with aging off of their parents’ insurance.

“Obviously it sucks,” Allie Marotta said. “Being postgrad, figuring out your career — all of that is crazy to begin with, and then adding the layer of worry about medical stuff and having it be a life-or-death situation, literally a life-or-death situation all the time. It shouldn’t be this hard. You see other countries doing it and it’s not this hard. There’s no reason for this to be the way that it is.” ●