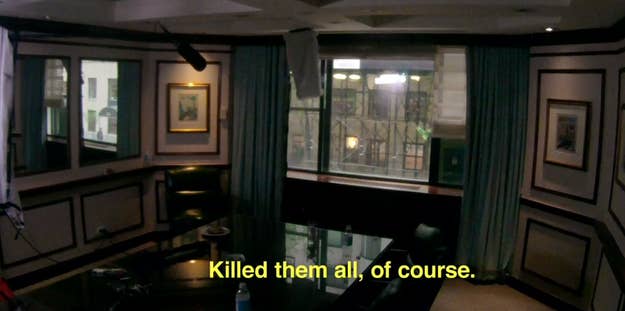

Sunday night's finale of the HBO documentary The Jinx ended with a bombshell. The subject, Robert Durst — the son of a New York City real estate tycoon and a suspect in three separate murders — was recorded in a bathroom wearing a live microphone. In an unguarded moment of solitude, and after being confronted with new evidence linking him to one killing, Durst muttered, "What the hell did I do? Killed them all, of course."

The apparent confession was only discovered by the HBO filmmakers in June 2014, about two years after the April 2012 interview, director Andrew Jarecki told the New York Times.

At court hearing Monday in New Orleans, where Durst was arrested, he agreed to go to Los Angeles to face charges relating to the 2000 murder of Susan Berman.

Now, questions have been raised as to whether his apparent "confession" could be admitted in court.

"His defense team has a tough road ahead," said Silas J. Wasserstrom, a law professor at Georgetown University and former chief of the appellate section of the D.C. public defender service.

(Coincidentally, Wasserstrom also said he went to the same high school as Durst. "I don't remember him, but my wife was in his grade and she does," he said.)

Did Durst have an expectation of privacy in the bathroom?

Durst's defense could try to argue that the recording is inadmissible because it was made when the wealthy eccentric was alone in a bathroom and had an expectation of privacy. But a number of legal experts told BuzzFeed News that argument would be unlikely to succeed.

Wasserstrom rejected the expectation of privacy argument. "If it happened the way it's been reported, that he muttered this in the bathroom, I don't think there's any [constitutional] issues here," he said.

Moreover, Jarecki argued to the New York Times that there was nothing "surreptitious" about the recording, because Durst had been well aware he was wearing a microphone during the interviews.

This issue of Durst's "consent" to the recording was also raised by Daniel C. Richman, a law professor at Columbia University.

"While California's interception laws are more demanding than those in many other states, the consent of the ... sole participant to the 'conversation' is enough," Richman told BuzzFeed News.

"While Durst might end up arguing otherwise and facts might come out to aid his argument," Richman said, Durst's knowledge that he was wearing a microphone "likely counts as a consent."

Did the film crew act as law enforcement agents?

One of the major legal issues confronting the admissibility of the recording deals with criminal procedure, Erin Murphy, a law professor with New York University, told BuzzFeed News.

The main criminal procedure issue is whether Durst's lawyers could argue the filmmakers were acting as "adjuncts or agents of law enforcement" in violation of the Fourth Amendment's restrictions in search and seizure, Murphy said.

"If the Fourth Amendment restricts police in what they can do to collect evidence, then we wouldn't want them to be able to easily circumvent those restrictions just by enlisting private citizens to do the search," she said.

Still, she said, "the law assumes that evidence found by private citizens and brought to police is fair game — so if I find a discarded gun on my porch, or my friend confesses a crime to me, I can go report that to the police and it's useable evidence."

At issue here will be the extent of collusion, if any, between law enforcement agents and Jarecki and his documentary team before the interview.

In a statement on Monday, Jarecki said he turned over the evidence his team assembled, including the bathroom recording, to authorities "months ago."

Jarecki is yet to fully clarify the timeline of his interviews with both police and Durst. He told the Times that he first began speaking to Los Angeles investigators in 2013, after the bathroom recording was made. If that's true, that would indicate that the filmmakers were arguably not acting as law enforcement agents, Murphy said.

"If the filmmakers went to the police before the final interview then conceivably there could be an issue, but it doesn't look like the government played much of a role," Wasserstrom said. "They didn't plant a microphone that he didn't know about."

Is the audio reliable evidence?

The other major legal question concerns evidentiary issues, Daniel J. Capra, a law professor at Fordham University, told BuzzFeed News. Capra said there is a small chance that a court may find the recording "unreliable and therefore not probative."

This concern deals mostly with whether the recording can be proven to be authentic or if it was altered during the years it was in the filmmakers' hands, Murphy said.

"These are filmmakers," she said. "Even if they're documentary filmmakers, their interest is in a good story. Therefore there may be questions as to whether this tape was edited or altered in any way, and whether it is in fact a fair depiction of what was said."

If the circumstances in which Durst was recorded were somehow deliberately orchestrated with nefarious intentions, a judge may find find that the audio would prejudice a jury more than provide them with useful evidence, Murphy said.

In a piece for Bloomberg, Harvard University's Noah Feldman hinted that prosecutors would have to prove that no one stepped in and adapted the audio and that the filmmakers knew who had access to it — known as chain of custody. "They claim to have discovered it after two years," Feldman wrote. "The chain of custody of the recording during that time must be known, to be sure that it was actually made by Durst, and when."

Feldman also argued the recording would be inadmissible because it amounted to a "soliloquy" of an ambiguous nature and would thus be too prejudicial. "He could be musing on what he might say to the camera. He could be fantasizing. The possibilities are endless — and almost all are different from an actual admission," Feldman wrote.

But if a judge does deem the recording is authentic, Murphy said that any subsequent questions over whether Durst was simply posturing or truly confessing to the murders would all be matters for a jury to determine.