The US overdose crisis has only worsened during the coronavirus pandemic, and public health experts are calling for more drastic measures to get it under control.

More than 91,000 people died of drug overdoses nationwide in 2020, according to initial CDC data, a 30% increase in one year. But it’s unclear how far the Biden administration is willing to go to address the crisis, which experts say could take unprecedented and divisive interventions like safe injection sites for people who use drugs.

“Things were on a bad trajectory before, and now it has gotten even worse,” said epidemiologist Chelsea Shover of the UCLA David Geffen School of Medicine.

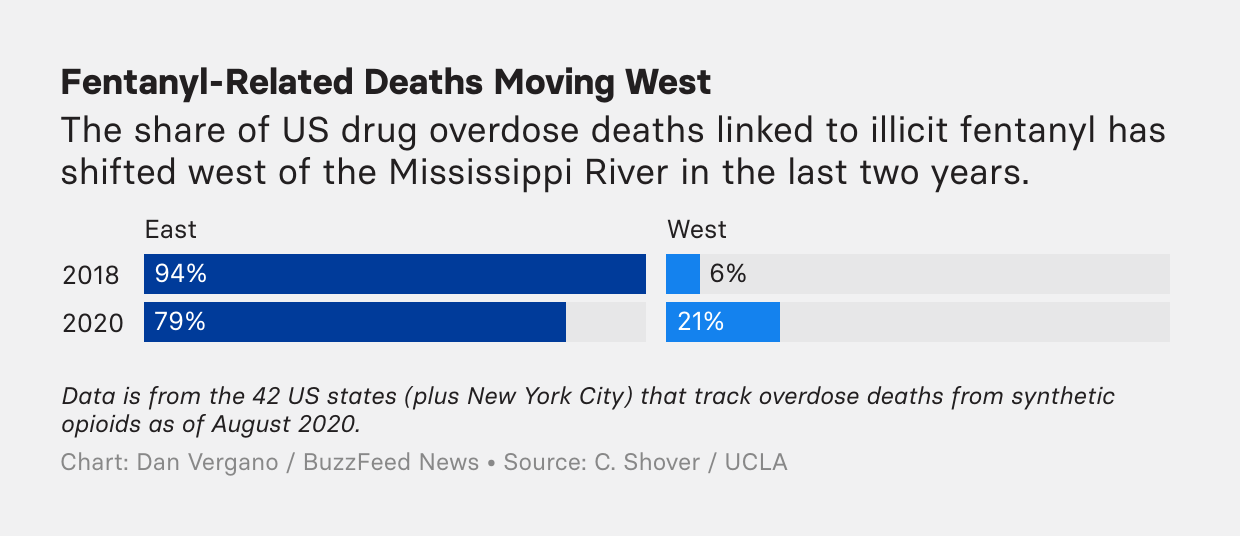

The drug still driving overdose deaths is fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that had largely replaced heroin in the illicit drug market on the East Coast and has now spread west, her research shows, showing up in fake pain pills and in cocaine in states like California and Washington.

“I can’t think of a way the pandemic made things better,” Shover said. “The simple fact that people are more isolated, and more likely alone when they overdose, means they can’t get help.”

The damage to the nationwide campaign to curb overdoses, a signature effort of the Trump administration, has become clear in the 30% increase in overdose deaths in the last year now seen in preliminary CDC data. The worsening crisis has recovery centers hoping to keep changes made during the pandemic that made getting access to treatment easier, such as telehealth counseling and allowing people to take methadone at home instead of lining up every morning for a dose.

Addiction experts, meanwhile, are calling for wider use of “harm reduction” measures that go beyond the nearly 300 needle exchanges now operating nationwide. They include checking illicit drugs for fentanyl in real time and operating facilities where people can safely inject drugs without dying of an overdose, also known as safe injection sites, which have been proposed in cities such as Philadelphia and Seattle.

But it’s unclear whether Biden will embrace such measures. So far, Biden has waived extensive training requirements for prescribing medication to treat opioid addiction, opening the door for more doctors to offer drug treatment, and released a drug policy blueprint that built on many of the Trump’s administration’s moves, including support for needle exchanges. But the president has so far stayed silent on safe injection facilities, and several states are even moving to shutter needle exchanges at a time when HIV outbreaks driven by drug use are increasing in places like Boston and Charleston, West Virginia.

The Department of Justice did not respond to questions about whether its views toward safe injection facilities have changed since a Trump administration news release in January reiterating that they were illegal under federal law. The Biden administration added $4 billion for substance use and mental health treatment in its coronavirus relief act, and it has proposed another $10.7 billion to combat the crisis in next year’s federal budget, but critics note that is short of the $125 billion proposed during the presidential campaign.

Essentially, every worrisome trend in the overdose crisis — more potent drugs, more mixed use of stimulants with opioids, and staggering numbers of deaths — has intensified during the pandemic. In an overview study released on Thursday, epidemiologist Daniel Ciccarone of the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, concludes a “fourth wave” of illicit drug use has arrived nationwide.

While earlier waves of the overdose epidemic started with the overprescription of opioid pain pills to mostly white populations in rural states, this latest one has moved into Black and Latinx communities. This fourth wave is marked by fentanyl sold as heroin, or mixed with stimulants like meth or cocaine.

“Fentanyl is the problem,” said Ciccarone. Made in labs, and some 30 to 40 times more potent by weight than heroin, fentanyl is now linked to 3 out of 5 overdose deaths in the CDC data for 2020. The movement of the drug out of the Northeast and Midwest and into other illicit drug markets is likely the largest recent driver of the increase in people dying from overdoses. Easier to smuggle because less is needed per hit sold on the street, the economics made the drug even more attractive to criminal cartels during pandemic restrictions on US–Mexico border crossings, from which much of the illicit fentanyl and methamphetamine sold in the US originates. At the same time, overdose deaths linked to cocaine and methamphetamine, the latter once rare, now exceed those from pain pills or heroin.

“Meth is the new ‘it’ drug,” Ciccarone said, noting the higher-potency doses of the drug now sold on the street.

Mixed use of drugs, depressants with stimulants, also seems to have risen, worsening a prepandemic trend.

“We will be researching the reasons why for years,” Ciccarone said.

The continued increase in overdose deaths is particularly disappointing because of what looked like signs of a turnaround in 2018, James Carroll, head of the Office of National Drug Control Policy in the Trump administration, told BuzzFeed News in April. That year saw US life expectancy stop declining for the first time in three years. It was also the first year in 28 years that saw a decline in overdose deaths, by 4%.

“Things were working,” said Carroll, who is now working with Students Against Destructive Decisions, or SADD. “We had more money going to prevention than ever before. We had more money that went to treatment for those suffering from the disease of addiction than ever before, and seizures were at an all-time high. And then the pandemic hit.”

In retrospect, the 2018 decline in overdose deaths now looks more due to the removal of carfentanil, an unbelievably dangerous opioid roughly 100 times more potent than fentanyl that was linked to outbreaks of overdose deaths in cities like Dayton, Ohio, said health policy expert Hawre Jalal of the University of Pittsburgh. Harm Reduction Ohio has concluded the Dayton outbreak was tied to carfentanil in cocaine, based on drug seizure data.

The resumption of an upward trend in overdose deaths matches projections that Jalal and colleagues made in a 2018 study. “The trend has been rising for 30 years, and it has only been accelerating in the pandemic,” he said, adding that more recent analysis suggests the trend may date back as far as 1959.

The trends mean more emphasis needs to be placed on the demand side of the illicit drug market, expanding “harm reduction” efforts to help people not overdose, said Ciccarone, rather than what’s been the focus for the past few decades: heavy policing aimed at limiting supplies. Since the drugs circulating are now much more potent, the US should be looking at safe consumption sites and systematically checking illicit drugs for fentanyl to issue public health warnings, he added.

“It’s not like we have tried real hard on that side, and it hasn’t worked. We’ve hardly tried enough,” he said.

In January, the Trump administration won a legal victory against safe consumption sites over the Safehouse nonprofit in Philadelphia. A federal appeals court voted 2–1 that such sites would violate a federal law under the 1986 Controlled Substances Act, known as the “crack house statute” according to the Congressional Research Service, aimed against opening any place where people may knowingly use illegal drugs. The Biden administration, though, has so far stayed silent on the issue.

Safehouse is considering further appeal, Ronda Goldfein, a member of the group’s legal team said in an email. And she voiced optimism that the Biden administration would respond favorably.

“As we pursue our legal options, the new administration is showing a change in its policy,” she said. “The federal Office of National Drug Control Policy is talking about harm-reduction for the first time in its history.”

Supervised consumption will not solve the opioid crisis, Goldfein added, “but as fatal overdoses increase, we cannot continue to ignore a strategy that works.”

More fundamentally, Shover said, basic barriers in medicine like Medicaid not covering “contingency” management treatment for cocaine and methamphetamine-use disorders (basically counseling accompanied by incentives for avoiding drug use) should be removed, and insurers should stop paying for recovery programs that don’t offer medication-assisted treatment with methadone or buprenorphine, which the government’s own research shows are most effective.

Even when that treatment is available, regulations determine how people can get it, she added.

“We have three vaccines for the pandemic in a year, and we don’t even give [people who use drugs] a choice,” Shover said. “You get maybe one, when it comes to recovery.”