A federal probe into potentially illegal practices by student loan debt collectors could provide relief to thousands of Americans struggling to pay off costly college debt.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is investigating whether some collection agencies are involved in lawsuits against student loan borrowers even when the companies can't prove their legal right to collect on the loans, according to agency documents and people familiar with the investigation. The CFPB is weighing "whether Bureau action is warranted" against the collectors, documents say.

If investigators can prove wrongdoing, thousands of low-income borrowers could be spared years of wage garnishment that would place them at greater risk for financial hardship, including bankruptcy.

The lawsuits mirror illegal practices by mortgage companies seeking to foreclose after the 2008 financial crisis. Banks have paid billions to settle charges related to "robo-signing" — the practice of swearing falsely that a person has direct knowledge about a loan and the chain of companies that owned it. The people claiming to have that knowledge turned out to be signing hundreds of affidavits a day, often without reviewing the underlying loan files.

The investigation is another reminder of the troubling, and sometimes illegal, practices targeting student borrowers. The Education Department recently cut ties with five collection agencies it said were providing inaccurate information to borrowers, and scammers are aggressively targeting student lenders with phony debt forgiveness schemes, just as they did with distressed mortgage holders during the collapse of the housing bubble.

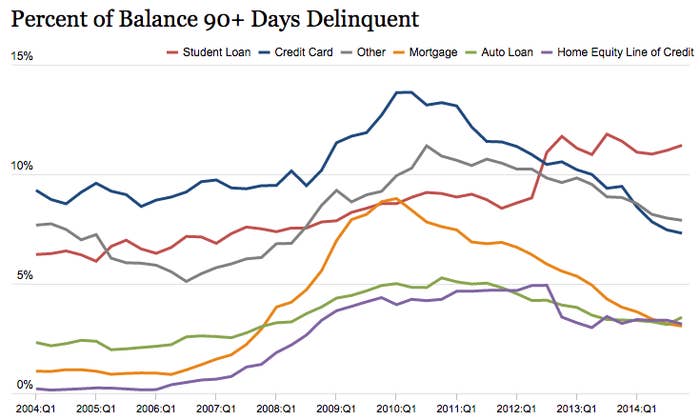

These kinds of issues are an unfortunate byproduct of America's $1.2 trillion pile of student debt turning sour. Federal Reserve data shows 11.3% of student loans were more than 90 days delinquent at the end of 2014, more than triple the rate for mortgages, making student debtors a prime target for questionable collection schemes.

Student debt lawsuits have flooded into state courts across the country over the past three years, consumer lawyers say. They say the cases typically hinge on affidavits signed by the same handful of people, all swearing to have personal knowledge of loans made years earlier by companies that they never worked for. The signatures belong to employees of Transworld Systems Inc., a private debt-collection company.

Transworld was hired on behalf of investors who own hundreds of thousands of private student loans worth billions of dollars. The loans were originated by all kinds of lenders, including major players such as Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase & Co. Transworld's lawsuits aim to collect on loans that were issued by these banks and then bundled into trusts and sold off to investors. The loans have passed through so many hands that it is often difficult for Transworld to document its clients' rights to collect on them, consumer attorneys say.

"They aren't able to produce the documents that are necessary" to identify the owner of the note, or to produce a witness who can testify about the history of the loan at trial, said Nancy Thompson, a consumer attorney in Des Moines, Iowa who has handled 10 such cases.

Nevertheless, many courts "are becoming rubber stamps for lawsuits — not making sure [debt collectors] have the right to collect" before entering judgments in favor of lenders, according to Robyn Smith, an attorney who has studied the issue and works with the National Consumer Law Center, a nonprofit consumer advocacy group.

Transworld officials did not respond to emailed requests for comment. An employee reached by phone said that "Transworld is a private company and does not grant interviews."

The CFPB in January issued subpoenas to Transworld employees, demanding interviews with them. Transworld's attorneys intercepted at least one of the subpoenas and later asked to be present at the private interview of an employee whose name appears on dozens of affidavits, according to agency documents. CFPB director Richard Cordray denied that request, according to a document posted on the agency's website Tuesday.

In 2013, Transworld and several affiliates paid $3.2 million to settle charges filed by the Federal Trade Commission that they had harassed consumers by calling them multiple times a day and calling them at their workplaces, among other illegal tactics. The companies did not admit to any wrongdoing.

A spokesperson for the bureau declined to comment because the agency cannot discuss ongoing enforcement probes.