WASHINGTON — In the aftermath of 11 states passing constitutional amendments in November 2004 banning same-sex couples from marrying, the leaders of ten LGBT organizations met in New Jersey to discuss what should happen next.

It was May 2005 and only one state — Massachusetts — had legalized same-sex couples' marriages. Reeling from losses in more than a dozen states, the movement to expand marriage equality was on the defensive, trying to preserve their victory in Massachusetts and fend off an expected "anti-gay-relationship initiative" in California.

On June 21, 2005 — one decade ago to the day — the group published a document titled, "Winning Marriage: What We Need to Do." While late versions of this plan have been publicized, this statement — agreed upon by 10 groups at a time when the future of the marriage equality fight was in real question — is a "concept paper" that formed the basis of much of the work that followed. Never before published, a copy of the full statement was provided to BuzzFeed News.

The document, which represented a compromise among the leading LGBT groups, outlined a recommitment to go forward with the fight for marriage equality. And it came with a strategy and a timetable — 15 to 25 years — that, in retrospect, looks modest.

But a decade ago, there was not unanimity, even among the LGBT leaders who participated, on the wisdom of pursuing marriage rights for same-sex couples. There is a three-paragraph addendum included in the statement addressing the "critical assumption" of why the fight for marriage equality was the path forward.

"Many people in the LGBT community would have preferred not to have made marriage a leading issue now. Many would have preferred to have addressed the legal and social recognition of same-sex couples with different tactics and/or with different conceptual models," the document stated. "Some members of the working group that drafted this concept paper are among those people."

The group — which included key marriage equality movement leaders like Freedom to Marry's Evan Wolfson and Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders's Mary Bonauto — concluded, "There is no way that gay people can be full participants in American life as long as society and the law treat our relationships as if they were inferior or as if they did not exist."

In addition to Bonauto — who argued for marriage equality at the Supreme Court this April — and Wolfson, leaders from the Human Rights Campaign, Task Force, Lambda Legal, ACLU, National Center for Lesbian Rights, Equality Federation, National Black Justice Coalition, and Basic Rights Oregon participated in the New Jersey meeting and preparation of the "Winning Marriage" statement.

"[O]ur opponents have already seen the possibilities and the dangers of this moment," the statement laid out. "We must give this everything we've got, and we must do it now." The document was blunt, declaring, "we cannot stop our opponents, if we simply continue doing what we are doing now."

The key goal for the movement, mentioned repeatedly throughout the document, was moving public opinion.

"Only with widespread public acceptance will the Supreme Court and/or Congress be ready to take marriage nationwide," the document stated. Even in the face of the losses in the prior election — and with the talk of a Federal Marriage Amendment in the air — the document boldly declared: "Winning the public cannot be something that is deferred to some more convenient time down the road."

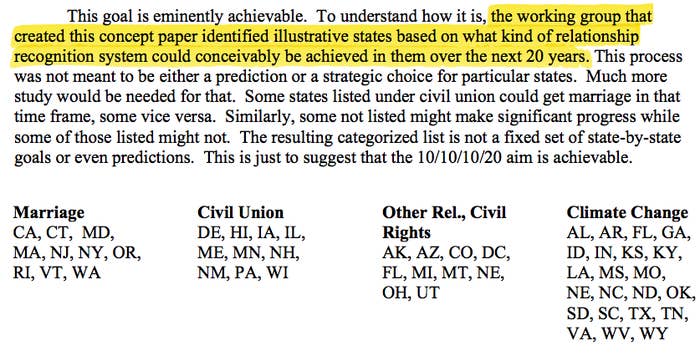

The group laid out a "10/10/10/20" strategy — winning marriage in 10 states, civil unions in another 10, domestic partnership benefits in another 10, and "whittling away" at the final 20 states.

The June 2005 timeline for this was 15 to 20 years — five to ten years from now.

The 10/10/10/20 Plan

The document laid out a plan that involved "[p]reserving marriage in Massachusetts" and "[d]efeating the expected anti-gay-relationship initiative(s) in California."

"If 30 or 35 states pass constitutional amendments, we will likely have to repeal a significant number of them before we can turn to the federal government to address holdouts," the document reads.

Massachusetts maintained marriage equality, but after a multi-year fight, California passed its marriage amendment, Proposition 8, in 2008.

When North Carolina passed its marriage amendment in May 2012, it became the 30th state to pass a constitutional amendment banning same-sex couples from marrying. None of those amendments have been repealed in a popular vote.

Despite setbacks, there was success on the fourth "short-term goal" highlighted by the group: Add 2 or 3 states to the marriage equality column in "4 to 5 years." Connecticut, Iowa, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Washington, DC all had marriage equality by the start of 2010.

The document laid out other goals that were not met, including a warning that, in addition to moving public opinion, the movement must "lose as few court cases as possible." Court losses in New York, Washington, and Maryland would soon follow, as well as a decision in New Jersey that was, at that point, limited to civil unions.

The document also said that the movement had to "start winning in state legislatures as well as in courts." Later that year, California's lawmakers would do so — but Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger vetoed the measure. In 2009, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, and DC passed marriage legislatively — although Maine voters repealed the measure in a referendum.

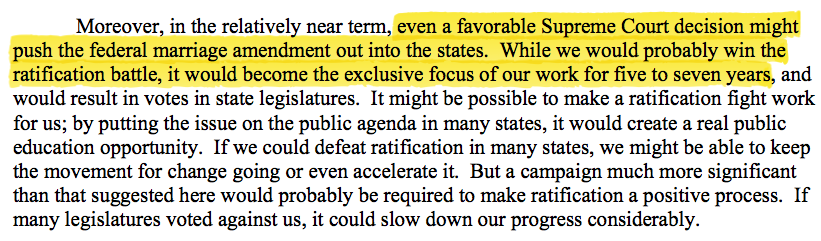

The statement also included a frank assessment of the Federal Marriage Amendment — a proposed constitutional amendment that would have ended marriage equality nationwide — in terms not generally discussed openly by LGBT advocates in that time or in discussions of that time in the time since.

"It might possible to make a ratification fight work for us," according to the statement — but warning that such a fight "would become the exclusive focus of our work for five to seven years."

Discussion of the Federal Marriage Amendment

More than anything, the document detailed an aggressive self-assessment in the wake of the past fall's losses.

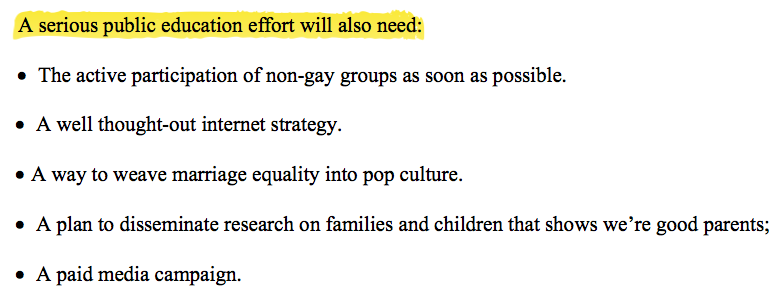

"While a significant body of research exists on the marriage issue, much of it has focused on how to defeat particular constitutional ballot measures and not on how to move public opinion on the issue of marriage for same-sex couples itself," the document stated in laying out the case for the public education campaign that the group saw as needed for success.

Plan for moving public opinion

The statement bluntly detailed the ways in which the group saw the need for the marriage equality movement to take on some of the elements that had been used against it in the past — from the "echo chamber" of politics to holding politicians accountable for their actions.

It described the need to "create a network of outlets, speakers, and writers who will echo our messages over and over again until they are rolling off the tongues of those in the movable middle as reflections of their own values."

In detailing its field plan, the statement asserted that the field capacity — which it stated must be present in "virtually every state" — must be able to be used "to help politicians who support us, and to hurt those who do not."

Notably, it also identified two areas that have continued to be raised as problems in national efforts, declaring that "state players must have a meaningful voice in all aspects of the campaign" and stating that "[t]he campaign must be racially diverse at all levels and must be designed to bring in new faces and new energy, both LGBT and straight."

In a second "critical assumption" — relating to "the role of the federal government" in their effort — the group made clear that they would not be going to the federal courts to address state marriage bans until "we have won in many states," a step that they said would come "fairly late in the process."

"Critical assumption" about going to the Supreme Court

And yet, less than four years after the groups agreed to this statement, Chad Griffin and his new group, the American Foundation for Equal Rights — with lawyers Ted Olson and David Boies — filed a federal lawsuit challenging California's Proposition 8 in May 2009.

At that time, three states — Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Iowa — allowed same-sex couples to marry.

Another federal lawsuit had been filed two months earlier, one challenging part of the Defense of Marriage Act — and done with the support of many of the groups that had been at that 2005 meeting.

Both cases would make their way to the Supreme Court, with the rulings bringing marriage equality to California — although no national resolution on that question — and ending DOMA's federal marriage discrimination.

The latest wave of litigation — and mostly successful court rulings for advocates challenging state bans — followed, leading to today.

Should the Supreme Court rule in favor of nationwide marriage equality in the coming days, debates about credit for that result will continue in the weeks and months that follow.

What is clear is that with only one real win in Massachusetts and more than a dozen losses, leaders of some of the biggest LGBT political and legal groups decided in 2005 that there was a path forward for marriage equality and that, as they put it, "the LGBT community has never faced a challenge so ripe with the prospect for success and carrying such risks if we fail."