WASHINGTON — When Shanta Driver, the attorney for the Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action, argued at the Supreme Court Tuesday that the purpose of the 14th Amendment is "to protect minority rights against a white majority," Justice Antonin Scalia was incredulous.

"My goodness," he said, telling Driver that he thought "the 14th Amendment protects all races," and that the view that it protected "only the blacks" had been rejected.

Driver pressed forward, saying that "the question of discrimination" is aided by looking at those with power and privilege and those who "need protection from a more privileged majority."

"Do you have any case of ours that propounds that view of the 14th Amendment, that it protects only minorities? Any case?" Scalia asked Driver.

"No case of yours," she replied curtly.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg held up the other side of the argument, pointing back to the pivotal 1930s case that established the levels of scrutiny that courts use to judge constitutionality of laws under the 14th Amendment — discussing "the judiciary's special role in safeguarding the interests of those groups that are relegated to a position of political powerlessness."

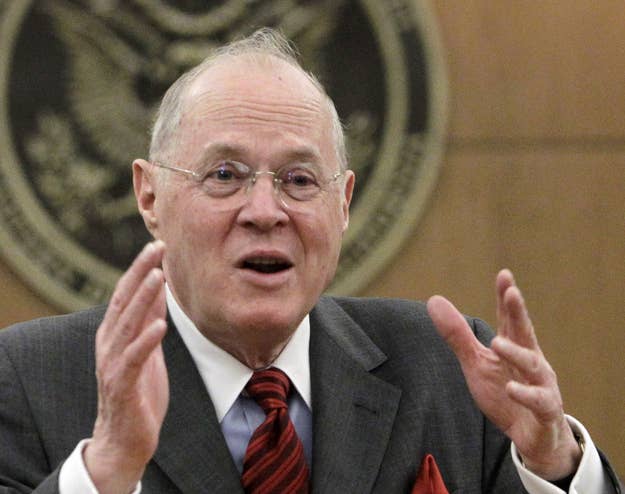

The heated exchange came during the court's consideration of a challenge to the 2006 Michigan constitutional amendment banning race- and sex-based affirmative action plans in higher education admissions, among other areas — a case that, despite the strong views at both ends of the spectrum, likely will come down to Justice Anthony Kennedy's interpretation of the 14th Amendment and past court decisions on the issue.

The Supreme Court held in 1982 in Washington v. Seattle School District No. 1 (referred to as Seattle) that an anti-busing initiative aimed at stopping a busing program in Seattle was unconstitutional because it restructured the political process to make it more difficult for racial minorities to obtain success in the political process. The Supreme Court has since held that a public university can, only under very limited circumstances, consider race in admissions in order to promote a diverse student body.

On Tuesday, the court hit on a case in between those two cases: asking whether states can, through a constitutional amendment or otherwise, ban consideration of affirmative action policies in higher education.

In Tuesday's argument, Mark Rosenbaum, an ACLU lawyer representing the plaintiffs challenging the amendment, argued that the case is about whether it is constitutional to pass a provision that "treats race different than all else" in removing race from the "ordinary political process," a reference to Seattle and an earlier Supreme Court decision about housing laws.

Rosenbaum said that the Michigan amendment should be found unconstitutional because a student who wants consideration of race in admissions needs to go from the "ordinary political process" used by anyone else who wanted any other consideration — like being the child of an alumnus — to the "extraordinary" process of amending the Michigan Constitution again to allow racial consideration. He argued that this restructuring of the political process, similar to the anti-busing initiative struck down in Seattle, is unconstitutional.

Kennedy's questions — throughout the arguments — suggested an ambivalence about the extremes pressed both by Scalia and Ginsburg. Instead, he appeared to be focused in finding whether a workable line could be drawn that would explain when such "restructuring" of the political process is unconstitutional.

Following up on a question from Chief Justice John Roberts, Kennedy asked whether it would be constitutional if the faculty at a school voted for an affirmative action policy and then the Board of Regents took the power away from the faculty a few years later. Rosenbaum said that would be allowed. Kennedy then asked if the legislature could take the power away from the regents, which Rosenbaum said would be fine if "part of the ordinary process."

As he continued moving up the line to the amendment process, which Rosenbaum argues is unconstitutional, Kennedy, slightly exasperated, asked, "At what point is it that your objection takes force? I just don't understand — I just don't understand."

Rosenbaum didn't give a Kennedy a bright line, instead telling him that "the problem that the restructuring process gets at ... [is that] the political process itself not become outcome determinative," leaving it to Kennedy and the other justices to decide whether such a line can be drawn.

Scalia — who has made his opposition to all racial preferences clear and, as such, would not have any issue with a state banning such preferences — served as the key defender of the Michigan amendment, telling Rosenbaum that under the ACLU's argument "the 14th Amendment is a racial classification."

The chief justice and Justice Samuel Alito expressed similar sentiments as Scalia throughout the arguments. "You could say that the whole point of something like the Equal Protection Clause is to take race off the table," Roberts told Rosenbaum at one point.

Justice Clarence Thomas, as usual, said nothing Tuesday, but has expressed opposition to racial preferences throughout his time on the court.

With Justice Elena Kagan having recused herself from hearing the case, Kennedy's final view on whether the case is distinguishable from Seattle and whether the pair of "political restructuring" cases should be overruled or more narrowly applied going forward, likely will determine the outcome in the case.

Because of Kagan's recusal, a 4-4 split, with Kennedy siding with Sotomayor and Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer, would uphold the appellate court ruling striking down the amendment — although it would not establish a national precedent applying to other such bans.

The eight remaining justices considered the arguments made by Michigan Solicitor General John Bursch as to why the Sixth Circuit was wrong and the measure should be allowed.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor led off the questioning against Bursch, asking him why this case wasn't "identical" to the anti-busing initiative case. Bursch pushed back that the busing case was about "trying to create, in the court's words, equal educational opportunity," which Sotomayor countered supporters of affirmative action would say is their aim as well.

In his first comment of the argument, Kennedy echoed Sotomayor and gave hope to supporters of affirmative action, saying, "I have difficulty distinguishing Seattle."