The most dramatic reveal of Fifty Shades of Grey isn’t the Red Room of Pain. It’s not Dakota Johnson’s pubic hair, or even Jamie Dornan’s abs. It’s Christian Grey’s penthouse: bathed in 50 shades of West Elm, with a panoramic view of Seattle. The proceeding scenes had functioned as capitalistic foreplay: We see his towering office buildings, with the crisp white and stainless steel that connote very important business going on here.

The women wear tight but super-formal suits with French twists, the actual embodiment of sexy fancy money. Grey’s suits are tightly fitted, and his repeated action of standing up, buttoning his suit jacket, and sitting down at his desk to unbutton is filmic shorthand for seven-figure income. Then there’s the matter of his driver and helicopter: two things that subtract all that’s unglamorous or uncomfortable about getting from one place to another. And more than fancy fabrics or expensive diamonds, that’s what signifies luxury today: freedom from inconvenience.

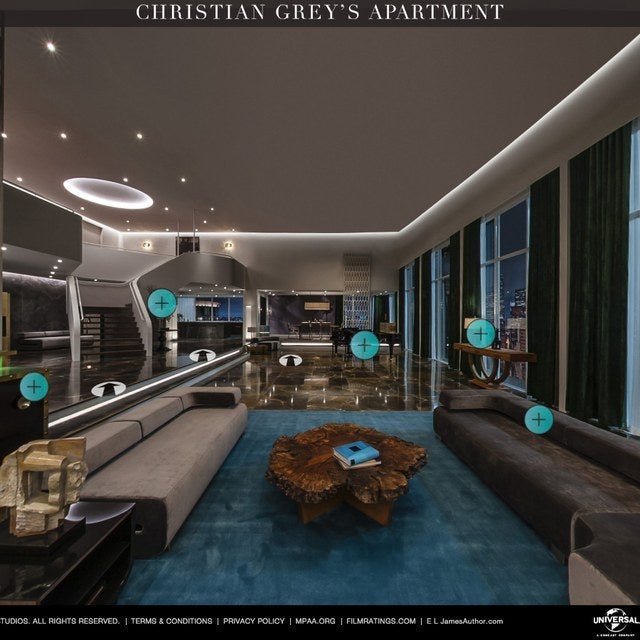

Grey’s apartment seems a natural extension of that luxury. He steps off the helicopter and directly into his home, where all manner of high-class goods — clothes, food, wine — magically appear. One look at the Focus Features website designed around it, complete with tours of each room, wine and food suggestions, and the opportunity to take a screenshot of the space and share it with your social network, and the actual fetish objects of the film become stunningly transparent.

In this way, the sexual fantasy that undergirds Fifty Shades of Grey is inextricable from the class fantasy: No one would be compelled by the fantasy of a man who gets off on restraining and whipping a woman in trailer park, or even a suburban split-level. The eroticism is rooted in desire, in lack, in curiosity: What would my life be like if I were sexually submissive? is just as a central question as What would my life be like if I never had to worry about money?

Christian even articulates as much. He conceives of control not as punishment, but the ultimate in liberation: to be oneself, to experience pleasure, to revel in the absence of choice.

In his “contract,” Grey outlines all the ways in which Ana must be submit to his demands: He’ll control her health, her drinking, her diet, her method of birth control; how many nights they’ll stay together; when and how she’ll respond to his sexual demands; how she’ll be treated if she disobeys him. We’re meant to understand that Ana doesn’t have taste (she can’t dress herself; she drinks cosmos) or means (she drives an old Volkswagen Beetle; her computer is dead), so someone controlling that taste and offering her means, however circumscribed, is something like freedom — freedom from thinking, from deciding, from choosing: all the things that characterize our exhausting and overstimulated existence within capitalism.

Here, Grey reproduces the rhetoric espoused by cultures past and present in which submission to patriarchy is figured as emancipation from vanity, worry, and self-consciousness. Every woman should be so lucky as to have someone to tell her how to live her life. It’s not difficult to see how this scenario, however seemingly regressive, morphs into fantasy: Sure, you surrender a modicum of free will, but free will is exhausting.

And even though we never get the sense that Ana is a gold digger, she’s absolutely awed by Christian’s bounty. When we see the view from the penthouse, or the 360 of “her room,” or even a beautifully poured glass of wine, it’s all shot with the wonder and beguilement as seen through Ana’s eyes. And Ana, like Twilight’s Bella Swan character with whom she shares significant DNA, is a classic cipher: a fairly undeveloped character onto whom female readers of the book can map themselves and, by extension, surrender more fully in the fantasy scenario.

You can feel Ana’s desire and apprehension when Christian first climbs on the bed and eats a bite of her toast; you feel her writhing anticipation as he binds and blindfolds and slips an ice cube down her chest. But you also feel the glee at having a fashionable and expensive outfit waiting for you every morning, and the revelry in a massive, open-design kitchen fully stocked with infinite breakfast items and beautiful kitchenware. And no need to clean up! It’s like a scene straight out of a harried, working mother’s daydream.

Unexpectedly, Fifty Shades, at least in its filmic version, does something fascinating with this fantasy space, examining just how hollow this vision really is once obtained. Christian, after all, is a hollow version of a capitalist: His wealth simply is; his “business” consists of one scene of yelling Get it done in 24 hours! into a phone. Only the appearance of business, no actual labor. And the capitalist fantasy — of the penthouse, of her own room — soon seems shabby, even seedy, once held up to closer scrutiny. It’s almost as if the last third of the film was shot through a different, darker lens as the luxuries reveal themselves, like Grey’s business, to be little more than a front to cover a gaping emotional and psychological abyss beneath.

Ana’s hesitancy to sign the contract — which would render her a component of his financial and emotional enterprise — signals her dubiousness toward the entire scenario. The fancy dresses are nice, and so are those early (assumed) orgasms, but she sees that even a fully furnished room of her designing is still a room in which she must spend her nights alone.

When Ana leaves Christian at film’s end, it’s ostensibly an indictment of his inability to open himself up to love and vulnerability. But she’s also grown disillusioned with the “freedom” of luxury: She returns the glossy MacBook he bought for her and asks him to return her VW, only to learn that it’s been sold. Instead of an actual mode of transportation, however old and clunky, she’ll be left with a barely enough to buy bus fare — literally stranded by her faith in the fantasy of wealth. Ana rejects Christian’s vision of control and subsequent liberation through sex, but she’s also saying fuck you to the theory that a life of luxury will inure a woman to the lack of true companionship, respect, communication.

For Fifty Shades to end as it does, with such a clear rejection of both Christian and the lifestyle he promises, is a radical act. The scene in which Christian whips Ana — and forces her to count along, complicit in her own abuse — is a searing commentary on what women are willing to endure for the promise of love. Ana is essentially rejecting the ideals (hot dudes, perfect body, endless privilege) to which popular culture has taught us to surrender and, in so doing, she explodes them. The hot dude is rotten inside; his version of BDSM isn’t about mutual pleasure, but using his capital to compel women to endure sex that they don’t like so that they can enjoy the lifestyle they do.

That’s an uncharitable understanding of any man’s intention, but the text, with its flimsy characterization and hackneyed psychology (childhood abuse yields adult perversion) gives us little reason to believe otherwise. Yet fully drawn character and cohesive plot has never been the point. People didn’t buy this book or see this movie merely because it’s erotica. It can, in a spare number of scenes, genuinely arouse, but what’s really compelling about Fifty Shades is the way in which it negotiates the knife-edge between control and release, freedom and submission, both sexual and financial. BDSM simply becomes the taboo playground on which those larger, enduring, and never more essential ideas are set out.

Like all fantasy, it’s less about actually submitting or dominating and more about thinking about it. We’re not meant to treat Fifty Shades as a how-to book, which is why most (but not all) debates over the way in which it might inculcate domestic abuse lack nuance. Such thinking harkens back to old, thoroughly disabused theories that a film, book, or song is a hypodermic needle that, once injected in its viewer, reproduced its values in its new host. Instead, women — and some men — are watching Fifty Shades and processing how that vision of surrender, and Ana’s ultimate rejection of it, meshes with their own ideas of freedom. That’s how we consume media: We digest it.

The problem, of course, is that the full Fifty Shades narrative doesn’t end with Ana’s rejection. It’s a momentary pause before the pair are reconciled at the beginning of the second movie. Love and communication “fix” Christian’s perversions, leaving the pair to marry, have children, and live out the bourgeois fantasy that soured so effectively at the end of the first movie. Indeed, the biggest spoiler of the Fifty Shades trilogy is that a potential deviant text so thoroughly and unproblematically reifies the status quo. On its own, however, this first Fifty Shades might just be an indictment not only of capitalism, but the exploitative sexual contracts, formal or implicit, that women submit to in its service.