When we meet Trainwreck's Amy (Amy Schumer), it seems like she's living her best life: She has a ton of sex, a well-muscled guy who takes her to the movies, a fantastic ponytail, and great legs. “I have a great job and my apartment is sick,” she says in voiceover, a montage of her fabulous Manhattan life playing in the background.

But after 15 minutes in this world, the cracks in Amy's fabulous life start to show. She has a lot of sex, but that sex largely sucks; she has a well-paying job, but it’s at a magazine that unironically pitches “You Call Those Tits?” as a cover story. She drinks not because she loves it, but because she’s frightened of the emotions that surface when she doesn’t. She’s promiscuous not because she loves sex, but because she’s internalized her father’s message that emotional unavailability is preferable to rejection. Like her father, she’s a total misogynist.

Sure, Amy screws, drinks, and writes like a man, but none of those things actually empowers her, or vaults her to a position of equality, or even makes her feel awesome, or competent, or in control. We laugh when she hobbles home from Staten Island in a miniskirt and stilettos that have cut her heels into oblivion, but it’s a laugh tinged with shame: She’s a hot mess, a train wreck, and every other word we use to describe women who don't mind the very fine line of “just a fun, easygoing, cool girl!” and “total drunken whore.”

But it’s not her fault she’s a wreck — after all, the train tracks are rigged. Like so many women of her generation, she grew up surrounded by the ideology of postfeminism, which suggests that now that the “work” of feminism has been achieved we can all focus on having fun. The problem, however, is that “fun” is still circumscribed by patriarchy, and a woman’s worth is determined by her ability to hew to expectations of desirability. You can have a job, in other words, but actual success is only measured in your ability to simultaneously attract a man, maintain an ideal domestic space, and preserve your body.

And as manifest in Pretty Woman, Bridget Jones’s Diary, Sex and the City, and dozens of other pop culture artifacts of the time, postfeminism suggested that empowerment was best achieved through self-objectification, shopping, and sublimating anything that resembling engaged feminist politics. Feminism was the f-word. It turned women into humorless unfuckables, arguing over whether wearing lipstick makes you a traitor to your gender.

That was the postfeminism of the ‘90s — and easy, in hindsight, to disavow. Today, pop culture has embraced the term “feminism,” but that doesn’t mean that the ideologies of postfeminism are any less robust: They’ve simply changed forms. You can see it most visibly in American Apparel billboards and Vice, but it’s also in the cults of domesticity and motherhood, and the Pinterest-amplified fetishization of the baby/engagement/bridal shower.

That’s the dystopia that afflicts Amy’s sister’s friends: At the baby shower held in her sister's honor, their words, actions, even their posture hint at the deep sadness that undergirds the regression to quasi-Victorian conceptions of entertainment, adventure, and fulfillment. They’ve fulfilled the fantasy, but that fantasy is festering from within.

But Amy, like her fellow train wrecks on The Mindy Project, Girls, Bachelorette, Young Adult, and Bridesmaids, manifests a darker shade of postfeminism. Traditionally, sluttiness and self-objectification are the means to domestic end: Prostitute Julia Roberts becomes wifey Julia Roberts; Sex and the City becomes Married Sex and the City. But like The Mindy Project's Mindy Lahiri (Mindy Kaling), and Girls' Hannah Horvath (Lena Dunham), Amy gets stuck in a slutty, boozy holding pattern. They’re all disrespected at work and treated as objects on the street, so it’s no wonder they regard themselves and their bodies the same way.

The demands of the mainstream network sitcom necessitated that Mindy extricate herself from her holding pattern and into the arms of a suitable husband, but her character, like Dunham’s, has weathered consistent critiques of unlikability. These women are inconsiderate, self-indulgent, and total assholes. But that’s the point. Trying to fulfill the contradictory demands of postfeminism would turn any woman into a dick.

In these narratives, postfeminism stops functioning as the building blocks for a fairy tale. Instead, it takes on the pointed corners of dystopia. Which is why it can feel so bad to watch Girls, early episodes of The Mindy Project, and the first half of Trainwreck: They’re unflattering mirrors, in part because they make visible the ideologies that have become so natural as to simply feel like “the way that it is.” Guys don’t treat you like a human being worthy of respect? That’s just the “new dating.” Sex without pleasure? The way we have sex now. A work environment characterized by low-grade sexual harassment? The price of advancement. Making money by reproducing sexist rhetoric? Just playing by the rules.

That’s what makes postfeminism so sneaky and so noxious: Men don’t even have to subjugate women anymore, because women have so thoroughly internalized the ideologies that we do it to ourselves.

In Trainwreck, the tenets of postfeminism are inflated to the point of ridiculousness, but that doesn’t mean that they don’t touch on truths so familiar they verge on cliché: that female bosses can be even more misogynist than male ones, or that a man calling the day after a hookup is so rare that it must be interpreted as a butt-dial. It’s funny, of course, because it's too fucking real.

What distinguishes Trainwreck from other postfeminist dystopias, then, is the way that it offers Amy a narrative path away from it. That path does involve a man, but it mostly involves seeing herself as a person worthy of love, respect, and devotion — without necessarily disavowing her past or the unruliness that makes her character (and the film) so transgressive. She’s still, as fellow unruly woman Ilana Glazer of Broad City would put it, “a boss bitch” — she just doesn’t have to feel shitty all the time. (Abbi and Ilana of Broad City are essentially proof that not all women have to endure the dystopia before breaking free: They’re of the age that would’ve grown up on a diet of Sex and the City, but they’ve emerged unscathed.)

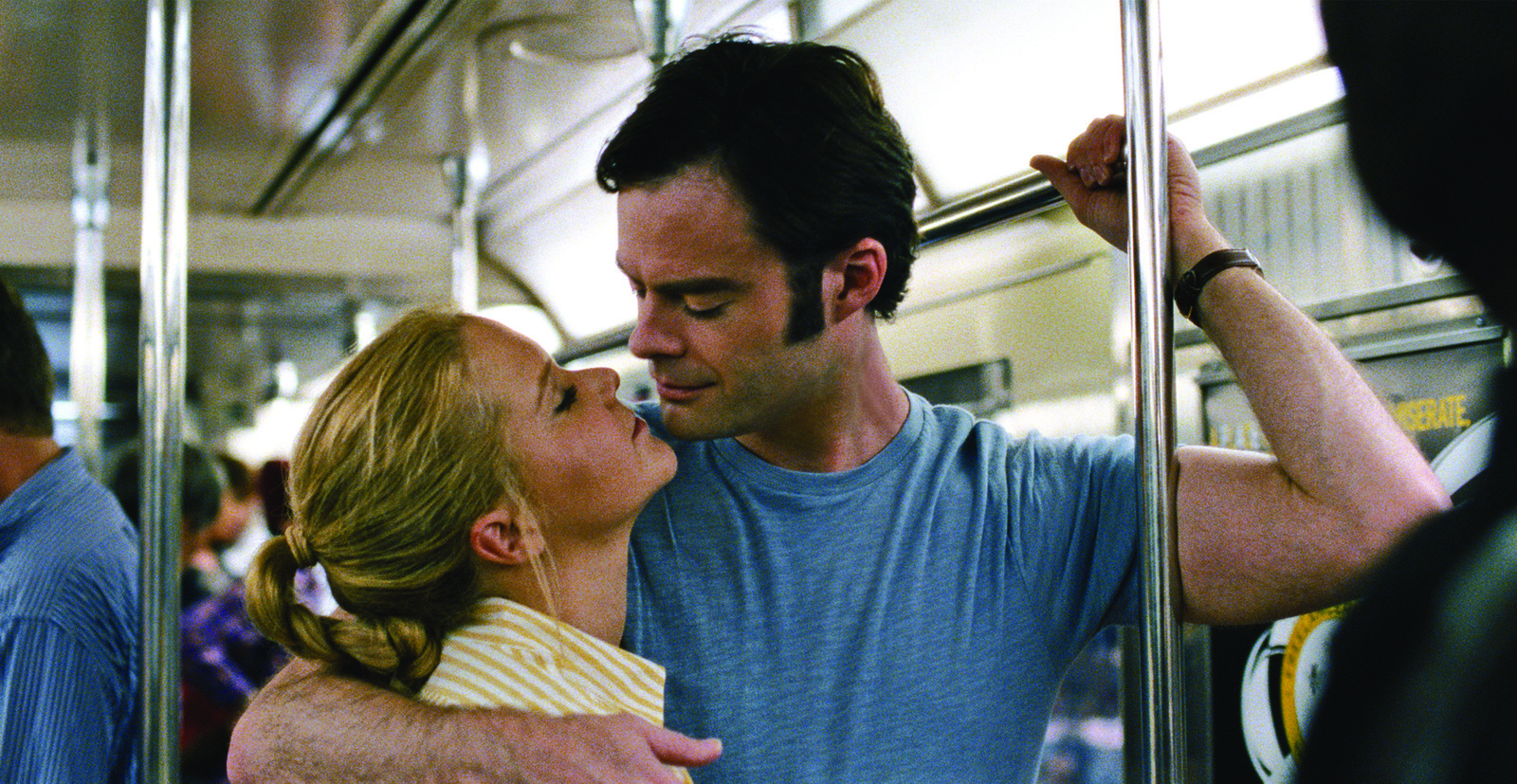

Amy’s romance with sports surgeon Aaron (Bill Hader) begins by treating him, and herself, the way she’s treated every previous relationship. She’s sexually aggressive, emotionally dismissive, and rebuffs his attempts at a second date. But Aaron — who, we learn, hasn’t had a date in six years — doesn’t realize his role in the postfeminist game. Amy may be profiling him for Snuff Magazine — which endeavors to “teach the strong-willed man how to dress, drink, and fuck” — but there’s zero evidence that he’s the type of man who’d read it.

Which isn’t to suggest he’s a manic pixie dream guy. Instead, he’s just a deeply decent man who values and practices straightforward communication. Instead of maintaining a chill hookup situation, for example, Aaron tells Amy, point blank, that “I think we like each other and should start dating.” She’s stunned by it: not because he likes her, but because he’s sincere without shame.

Sincerity — and frankness, and kindness, and intimacy — freak Amy out. That’s why she’s repulsed by her sister’s (totally decent and devoted and loving) husband, and even more confused by his tween son, who’s earnest about his love for the solar system, Minecraft, and his family. When she and Aaron fall in love, she’s even grossed out by that, making fun of the way they kiss on subways like two people who genuinely care about one another. When her sister (Brie Larson) tells her she’s pregnant, she responds with “ew.” And then there are cheerleaders, whom she hates in large part because they lack the sense of irony and detachment that shape Amy’s running life philosophy, in which it’s OK to degrade yourself so long as you know that you’re doing it.

When Amy’s dad dies, it forces her to reckon with this attitude, so clearly manifest in her father, and the relationships it builds. When he was young, her father was acerbic and carefree and a drunk but still likable; as he aged, those qualities curdled and, amplified by his multiple sclerosis, turned him into a bitter shell of a Mets-loving man. It’s not that he doesn’t love his daughters; it’s that he doesn’t know how to express that love in a way that’s not coated in bile.

Which is precisely the attitude Amy adopts in the immediate aftermath of her father's death, alienating her sister because she was less willing to speak the embittered language that Amy and her father shared. But it also clearly decenters her sense of self, as all the things that made her confident — the way she dresses, her skill as an author — come into question. When she attends a benefit honoring Aaron, it’s as if she’s adopted society’s censoring eye and directed it herself: Her dress is too slutty, she drinks too much, she’s not worthy of the man who loves her. So she reverts to the behavior that dulled her to the dystopia: drinking and smoking weed, which eventually leads to a breakup, a reversion to her pre-Aaron lifestyle (and a hookup that underlines just how preposterous that life is), and the end of her job.

You could read what happens next — getting rid of her bong, her drugs, her booze; selling her article to Vanity Fair; making up with her sister; learning how to dance like a cheerleader — as a classic reform narrative. (Bad girl figures out that her unruliness is the source of all unhappiness; becomes perfect lady in order to win back man.) There’s good reason to resist the notion that drinking “too much,” wearing outfits that are “too slutty,” and generally giving no fucks is tantamount to eternal misery, just as there are many ways of being unruly — having a body that’s “too big,” a sexuality that’s “too overt,” a mouth that’s “too big” — that are truly and enduringly empowering.

But it’s not as if Amy disposes of wry intelligence or eviscerating insight to win the man. She doesn’t lose weight, or buy a new wardrobe, or express anything like self-hatred. She just disposes with the behaviors she did out of fear. Which mirrors epiphanies from Schumer's own life, on which so much of Trainwreck is based — as she told The Hollywood Reporter, "I think this movie's a love letter to my sister, and the real way I realized I was hurting myself and being destructive was through falling in love."

In this way, Trainwreck suggests that neither romance, children, sex, shopping, jobs, sick apartments, nor even friendship with LeBron James can provide a shortcut to happiness. Instead, confidence, self-knowledge, and mercilessly rejecting anyone or anything that make you feel like shit — especially the contradictory demands of postfeminism — that’s something like bliss.

Regardless of how many celebrities and teens embrace the word "feminist," postfeminism continues to guide our expectations of how women should behave in public and private. Over the last five years, more and more narratives have highlighted the dystopic depths of attempting to adhere to those expectations. And so what used to be the narrative backbone of the perfect rom-com looks increasingly gnarled, unseemly, undesirable.

Which is all to say that the cracks in postfeminist ideologies, papered over so efficiently by the rom-com cycle of the ‘90s and ‘00s, are beginning to show. Trainwreck doesn’t dismantle postfeminism, nor does it lecture about it. Like the rest of Schumer’s humor, its power stems in no small part from its refusal to scold or shame. Instead, it shows that “the way things are” when it comes to expectations for women is, well, hilarious — but, most importantly, that it also doesn’t have to be this way.