Four years and eight days ago, Jennifer Lawrence reached Peak Cool Girl. Coming off the press tours for American Hustle and Hunger Games: Catching Fire, Lawrence, then 23, had spent the months prior performing her particular brand of hapless and adorable while oversharing in public. She chugged champagne, she tripped at the Oscars, she talked about butt plugs; she was hot and chill, dirty-mouthed but cherubic — a living manifestation of Gillian Flynn’s conception of the “cool girl,” first articulated in her 2012 book Gone Girl. “The Cool Girl never nags, or ‘just wants one’ of your chili fries, because she orders a giant order for herself,” I wrote in 2014. “She’s an ideal that matches the times — a mix of feminism and passivity, of confidence and femininity. She knows what she wants, and what she wants is to hang out with the guys.”

Lawrence never played a Cool Girl onscreen — not in her blockbusters (The Hunger Games, X-Men), not in the small, indie film that garnered her first Oscar nomination and national attention (Winter’s Bone), not in her two collaborations with David O. Russell (Silver Linings Playbook and American Hustle) in which she plays decidedly unchill female antagonists. Off camera, Lawrence said and did plenty of non–cool girl things. But that’s not what caught people’s attention: Whenever Lawrence did or said something that seemed to affirm her Cool Girl persona — drinking Veuve Clicquot out of the bottle on a picnic; freaking out when Jack Nicholson congratulates her at the Oscars — those moments became GIFs, and headlines, and proof of the authenticity of the image.

But a star’s image isn’t who she is; it’s a curated collection of moments, phrases, and photos that, taken together, convey a larger vision of how a woman could and should be in the world: an idea and an ideal. And in Lawrence’s case, that ideal took on a life of its own: articles revolved around it; late-night interviews pivoted on it. The image fed on itself, regenerated. The more people understood Cool Girl–ness as emblematic of J. Law, the more moments and GIFs and quotes needed to be harvested in order to maintain that understanding. For a star like Tom Cruise, or Tom Hanks, that cycle is sustainable: Men are taken seriously even when they’re not serious. But for someone like Jennifer Lawrence — whose image was formed on the basis of a smattering of behaviors between the ages of 22 and 24, during her precipitous rise to superstardom — it can become an albatross.

Back in 2014, at least, Lawrence seemed to embrace the image forming around her. Before The Hunger Games, she’d been sold as a sort of baby-faced ingenue: hot but talented, making bedroom eyes from the pages of Esquire, generally subdued or well-trained in her interactions with the press. Sometimes around 2012, that restraint seemed to fall away: If people liked it when she told weird stories, why not tell more? If pounding champagne made her likable, why not lean into it?

For months, all these GIFable moments seemed natural, which is part of why they were so charming. But then that naturalness began to fade, especially after she tripped (again) at the 2014 Oscars. As one Twitter user asked, “If Jennifer Lawrence falls and no one’s around... is it still quirky?” The Cool Girl image began to feel less, well, cool: few things seem less chill than (supposedly) tripping so people will make a GIF of you. Calculation, meditation, practice, preparation — they’re all so off-putting. So Anne Hathaway. So not Jennifer Lawrence.

Instead of “J. Law being J. Law,” suspicions arose that she was doing a shtick. Which, of course, it was: Every prominent person performs a shtick in public. Barack Obama has a shtick. The principal of your high school had a shtick. Some are just more seamlessly performed, and less discernible as shtick, than others. But when a man has a discernible shtick, he’s called corny. When a woman has one, she’s called fake, or phony, or accused of committing the ultimate sin for a woman in public: trying too hard.

Since this Cool Girl image first formed around Lawrence, it’s proven remarkably difficult to shake — even as she makes decisions and statements that should complicate it. Lawrence is now 27; she’s an immensely wealthy, award-winning actor who is, by any measure, one of the most powerful people in Hollywood. Yet she is rarely taken seriously. The Cool Girl, after all, is easy to love — and equally easy to dismiss. For some, “Peak Jennifer Lawrence” will always mean climbing over a row of seats while holding a glass of wine at the Oscars, rather than actually winning an Oscar, or being nominated for three more. This is the story of how Lawrence became the biggest female star in the world, but it’s also the story of how an image, especially for a young woman in Hollywood, can become a prison.

On the Sunday of Labor Day weekend in 2014, dozens of private pictures of Jennifer Lawrence — including several in lingerie, or otherwise partially clothed — were leaked online as part of what has since become known as the Fappening. Shortly thereafter, Lawrence issued a statement saying the photos, which had been hacked from her iCloud account, had been sent to her then-boyfriend. The images were not framed by the press — or received by audiences — as scandalous; if anything, the easy embrace and ownership of the sexuality suggested by the photos simply reaffirmed her Cool Girl image.

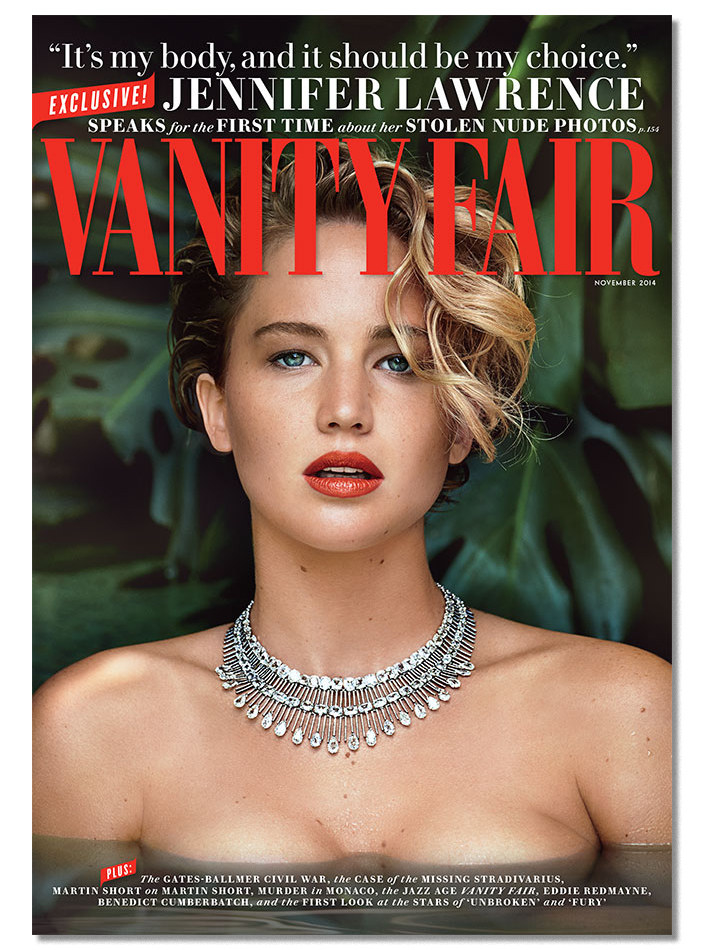

Three months later, Lawrence appeared on the cover of Vanity Fair. Inside, she didn’t joke about the photos. She was pissed — and spoke with a fury that would surface in the revelations of #MeToo. “Just because I’m a public figure, just because I’m an actress, does not mean that I asked for this,” she said. “It does not mean that it comes with the territory. It’s my body, and it should be my choice, and the fact that it is not my choice is absolutely disgusting. I can’t believe we even live in that kind of world.”

Lawrence’s response revealed just how flimsy, how oversimplistic, the Cool Girl image built around her was in the first place. Lawrence could be easygoing, yes. But she could also be filled with unmitigated rage. Lawrence’s anger at the violation was completely warranted, yet I recall, reading the profile, experiencing a flicker of annoyance: Maybe she should just calm down? I’d internalized the very ideologies that make the Cool Girl so popular: namely, that an angry woman is an unseemly woman, even when that anger is justified.

Before the hack, Lawrence had been circumspect about her relationships — she loved to tell stories about herself and her various mishaps, but if you listened closely, they always stopped short of crossing an unspoken border that cordoned off her truly private life. After the hack, she became even more private. She continued to stay away from social media, and remained largely out of circulation, periodically resurfacing for a glossy magazine interview and a handful of late-night appearances.

Her public appearances — with new best friend Amy Schumer at the 2016 Golden Globes; telling a reporter, backstage, to get off his phone and “live in the now”; describing sacred Hawaiian stones as “good for butt itching” on The Graham Norton Show — felt like they were too much. Same for her rumored romance with Chris Martin, fresh off his “conscious uncoupling” with Gwyneth Paltrow. Joy (2015) earned Lawrence another Oscar nomination, but the film as a whole was a critical disappointment — and proof David O. Russell could not cast her in even a decade’s proximity to her age. Serena, a Depression-era period piece released to VOD after years on the shelf, was an embarrassment. Passengers (2016) grossed over $300 million internationally, but struggled to counter audience sentiment that trailers had sold them on a very different, less stalkery, sort of movie. When Lawrence signed on to work with Darren Aronofsky, filming the very Aronofsky-ish Mother!, both the film and her relationship with the director were treated as abject and/or misguided. She was one of the biggest female stars in the world — yet somehow managed to disappoint at every turn.

She was one of the biggest female stars in the world — yet somehow managed to disappoint at every turn.

So much of the frustration, the fed-up-ness, and the fatigue directed toward Lawrence derived from lingering Cool Girl behaviors. Whenever she did something that seemed to confirm the Cool Girl core of her image (sending dubsmashes to Robert De Niro, forgetting to chill the rosé because she’s “new money,” or talking about her vacation alter ego, “Gail,” who basically just sounds like a frat bro), it came across as performative. But when Lawrence did or said something that undercut the familiar image (dating a dude who dresses like “the drama teacher on a Disney Channel sitcom,” agreeing to star in a deeply weird allegorical movie, writing a post for Lenny Letter about insisting on equal pay for American Hustle), it was ridiculed, ignored, or, in the case of advocating for equal pay, ineffective in changing the way people thought of her. Part of this souring is the press’s fault, part of this is her studios’ fault (especially for releasing a film like Mother! as if it were a mainstream movie), and part of this, of course, is our fault.

When it comes to Lawrence’s image, what we want for her is often a reflection of what we want or need to believe she is — even when a preponderance of evidence, including entire performances, suggests otherwise. Ahead of Red Sparrow, the brutal spy thriller released last week, I asked friends what sort of roles they’d pick for Lawrence, if they could map the next three moves in her career. Some responses were brilliant — an adaptation of Emma Cline’s The Girls, directed by a woman; a historical drama à la Meek’s Cutoff, again directed by a woman — but many suggestions were for roles, or variations of roles, Lawrence had already played: She should finally work with a female director (she has); she should do something like Erin Brockovich (see: Joy); she should do a mindless blockbuster (X-Men); she should be a ruthless, Angelina Jolie–like ass-kicker (truly, this is the plot of Red Sparrow); she should go indie again (hello, Mother!); she should be funny (watch her guest-host Jimmy Kimmel).

When a star’s image is so massive, it devours all nuance in the way we think of their ability.

That amnesia is understandable: When a star’s image is so massive, it devours all nuance in the way we think of their ability. Personality subsumes craft, leading to vague declarations of “star wattage,” framing it as innate and inexplicable, instead of a very real alchemy of talent and direction and timing.

And like so many massive female stars before her, Lawrence is a far better actor than most of her roles— or the discourse around them — reflect. She’s not Meryl Streep, or the Greatest Actress of Our Generation, or even able to get her Russian accent right in Red Sparrow. But her performance in Winter’s Bone remains revelatory, even as she’s been profoundly and repeatedly miscast, bogged down in franchises, and singled out as the last movie star. Her pay grade means she’s held to a different standard — a standard that’s simply not applied to her (white) male counterparts.

We see what we want to see. And the same goes for Lawrence’s actions offscreen: When she’s given alcohol during interviews — the most surefire way to bring out the Cool Girl — and she turns it into a joke afterward, commenters speculate she has a drinking problem. When she declares she’s taking the year off to focus on ending corruption in politics, it’s treated as unserious. Recent headlines focus on the specific obscenities she used to describe Harvey Weinstein, instead of the $500,000 she’s donated to Time’s Up, or her vocal and continuous support for its causes.

Lawrence seems increasingly frustrated that everyone keeps missing the point — misinterpreting or mismarketing her movies and generally ignoring any evidence of growth from the persona that solidified around her at age 22. When Howard Stern asked her about claims her appearance in a strapless dress on a cold rooftop — while the rest of her Red Sparrow cast wore suit coats — was “sexist,” Lawrence’s anger was palpable: “You’re loud, you’re annoying, you have no point, and what you also do is you make people hate a movement,” she said. “The women who have started Times Up, they’re actually moving legislature. ... And when these fringe people on these blogs start screaming about it, and just being annoying as fuck… You know me wearing a fucking dress isn’t not feminist, you know that.”

Lawrence isn’t mad at blogs, per se — she’s mad at the reactive metabolism of digital celebrity coverage, which does, indeed, distract from systemic issues in favor of the highly clickable “‘Depressing’ Image of Jennifer Lawrence in Tiny Dress on Freezing Rooftop While Men Wear Coats Sparks Fury,” which then, in turn, generate headlines like JENNIFER LAWRENCE PISSED ABOUT CLAIMS OF SEXISM. As with so many other female celebrities, if you listen closely to an interview that’s long enough, you can sense a particular sort of exhaustion — one that stems from the labor of trying to live your life in constant awareness of the ways others will misinterpret, repurpose, or otherwise appropriate its parts. In the conversation with Stern, that exhaustion is raw: because Lawrence is funny, and because the image of her created in her early twenties is rooted in chill, and because, as a 27-year-old, she periodically does or says things that still fit that image, most people refuse to take her — or her causes, or opinions, or acting — seriously. Wouldn’t you be angry too?

But does Jennifer Lawrence deserve our sympathy? Apart from her gender, she occupies the highest echelons of the Hollywood hierarchy: She’s blonde, she’s young, she’s skinny, she’s straight, she’s white. Dozens of other stars, from Joan Crawford to Julia Roberts, have carried the burden of similar image prisons. But the Cool Girl is a particularly inflexible one, which is part of the reason it goes in and out of fashion. In five years, Lawrence will be in her early thirties, past what Hollywood considers her prime and peak palatability, nearing the age when Cool Girl behaviors start to signify as desperate, even sloppy. After all, “coolness,” at least in this configuration, is contingent on youth, on carelessness, on not asking other people to take you seriously because you don’t take yourself seriously, on the performance of total sexual availability, on the ability to effortlessly maintain your figure while also eating anything and everything — a tension increasingly difficult to sustain past the age of 29.

“Coolness,” at least in this configuration, is contingent on youth, on carelessness, on not asking other people to take you seriously.

And Lawrence knows it: As she told Oprah, there was a moment, last year, when she was overwhelmed with fear: “All of a sudden it was, ‘They’re going to get sick of me.’ That’s when all my insecurity came. I’ve been probably more insecure after last year, and I don’t know if that’s just a feeling of: I’ve got more to lose, I have more people to disappoint.” It’s far more difficult, at this point in her career, to change the way that people think about her — or expand the boundaries of what meanings she can occupy in the public imagination.

What Lawrence does with the coming year off from acting — politically, but also performatively — will dictate just how intractable her image will become. Will she actually go on a college tour, to places like her home state of Kentucky, to fight corruption in politics? Will she use her clout to create a “hotline” to help women “that are not as ‘big’ in the world as me” in Hollywood? Will she start her oft-mentioned production company — and produce better projects for herself and other women? What if she refused interviewers’ attempts to feed her shots, or told her publicist she didn’t want to repeat a zany anecdote on late-night TV? What if she spoke, with clarity, about how difficult it is for a woman to be complicated in public, because she’s realized that it’s no longer cool to be careless — especially when it comes to politics, her platform, and its power?

But if Lawrence did any or all of those things, would we listen? Or, like so many female stars who’ve attempted to change the conversation about them, would she be labeled difficult, or ungrateful, or abrasive, or annoying in an entirely different way? That’s the thing about our fatigue with stars, especially female ones: Sometimes it’s because they won’t change. But sometimes it’s because they know that if they try, we won’t see it — or if they do change, we won’t follow. Just because you helped build your own prison cell doesn’t mean you can set yourself free on your own. ●