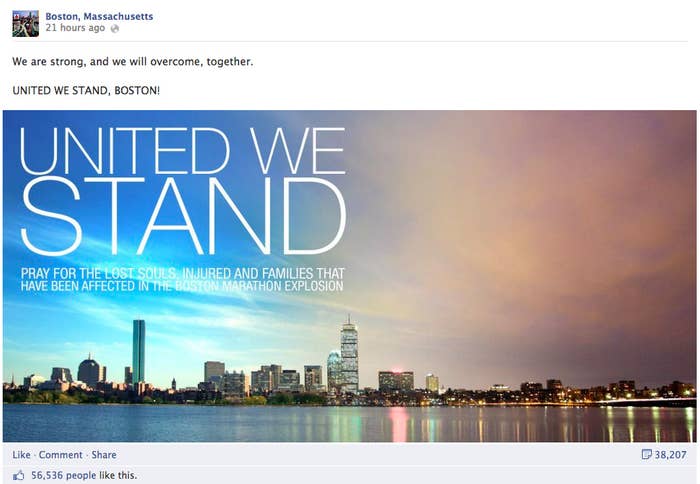

Monday's Boston Marathon tragedy was met with the expected flood of social media posts — and, as usual, mixed in with the news and speculation were reactions of disbelief and sympathy (and at least one fake marathon Twitter account that got more than 50,000 retweets before it was disabled).

Ordinary people are now broadcasting their responses to tragedies, when a decade ago, they would have been able to share them only with friends and family. Now that disasters are so extensively chronicled on social media, the pressure to respond seems to have increased exponentially. But it's possible we'd all be better off not sending that emotional tweet.

Of course, it's understandable why so many people feel the need to add their feelings to the flow of information. "After something like this happens, people just want to express their solidarity," says Karla Vermeulen, deputy director of the Institute for Disaster Mental Health at SUNY New Paltz. "They want to show they care about it, that they care about the victims in some way." But more than ever before, they feel they need to do so instantly: "There's so much more pressure to immediately jump into the stream of commentary."

Maybe it should be called Tragedy FOMO — that condition where people who look at party photos on Facebook feel a sudden "fear of missing out" and want to make themselves look just as busy and exciting as their pals. We may not want to look fun after a tragedy, but we also don't want to seem like we're ignoring what's going on. And it's possible that's what's leading us to post publicly about tragedy when we don't actually have much to say.

Cugelman thinks writing about our feelings on social media is "sort of like going to a funeral. You want to say something to the family, the ones who have the greatest loss." And that's not a bad thing, he says: Rather than taking away from face-to-face interactions, "it offers another channel."

But there are obvious downsides to using social media as a public grieving place. It opens up users to being scammed by opportunists spreading misinformation and capitalizing on grief. And there's the danger of politicizing the tragedy. "Everyone has their own agenda to begin with, and they can use an event like this to forward that agenda," Vermeulen says. Any heavy Twitter user knows that can (and usually does) lead to a stressful feedback loop where we're arguing about how we argue about the tragedy.

There's also a question that we rarely bother to ask: Do expressions of support from strangers — the tweets tossed off while in transit or the Facebook posts — actually offer any help to those affected?

Maybe not. "One issue is when [victims] get inundated with so many messages that are so superficial in nature," says Lisa M. Brown, psychologist and co-editor of Psychology of Terrorism. "The person feels it when they're writing it, but it doesn't make you feel any better."

Brown also says it's not just Twitter and Facebook — several email listservs she's on had to ask users not to reply-all with messages about Boston. "There was this outpouring that had a crippling effect on listservs," she says.

Gilbert Reyes, psychologist and coauthor of the Handbook of International Disaster Psychology, says social media postings can have some value to survivors if they're done in the right way. "I think they provide a sense of moral support," he says, a sense that "people care wherever they are." The best, he says, are "social media responses that are oriented towards doing some good, not just lamenting the bad" — responses geared toward raising money or debunking misinformation, for instance.

Most people who posted on social media after the Boston bombing did so out of genuine sympathy.

But some of us may also have wanted a way to work out our own shock and sorrow, or felt pressured to join the conversation around the tragedy lest we seem to be ignoring it. For feelings like that, it might be time to turn to Gchat or even the phone. "I think it's even more helpful to talk to a real person," Brown says. "Reaching out to another person is even more meaningful than a tweet or a posting on Facebook."