BERLIN — As bombs fell over Syria, Mohamed and his wife, Roqa, took their two young daughters, Rushin and Reema, and fled.

Now, two years and 1,500 miles later, I am sitting with Reema, discussing Disney's Frozen.

"You are Princess Anna and I am Queen Elsa," Reema tells me.

"But I am a lot older — I should be the queen," I say.

"But your name is Anna. It fits better," she laughs.

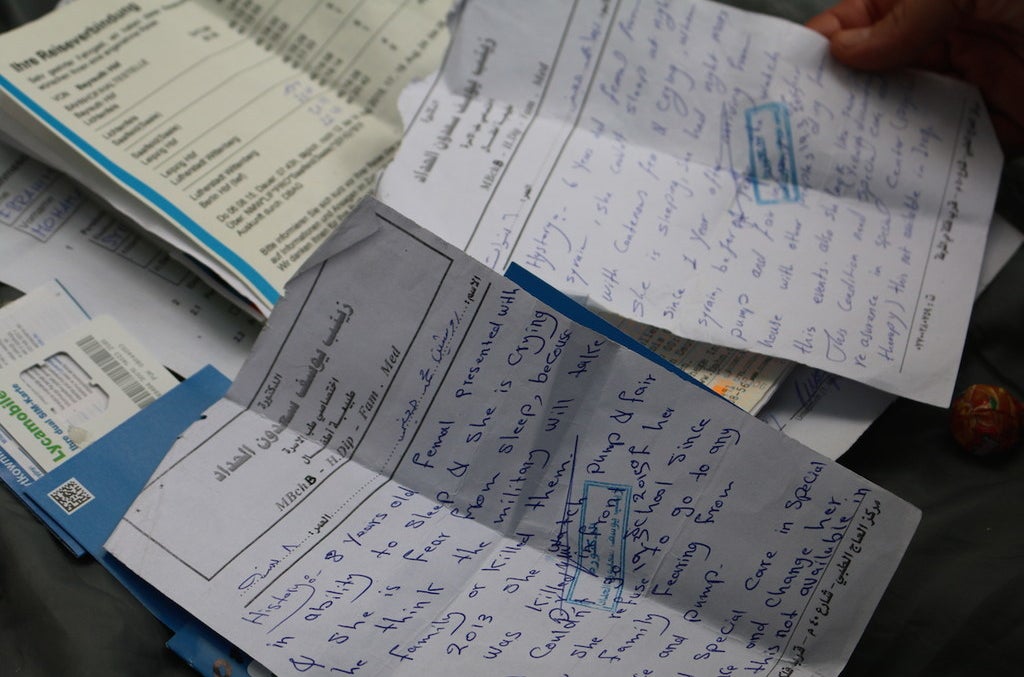

Now we're all sitting — me, Mohamed and Roqa, and their two daughters — in my kitchen. Mohammed and Roqa are telling me how they fled their home in Aleppo, Syria, and made it to Berlin. The elder daughter, Rushin, nods sometimes in agreement. She is 8 years old and doesn't sleep well at night. She has constant nightmares. Her parents, Christian Kurds, show me an official looking paper that confirms it. They got it from a doctor at a United Nations refugee camp in Erbil, Kurdish Iraq, to which they first fled in March 2013. Since then the children have rarely been in school. Reema, the younger one, tugs on her mom's arm to show her a drawing she has made of Princess Anna.

“It’s better to die at sea than from a bomb.”

I first meet the family the day before, on a Friday in August in the Berlin neighborhood of Wedding. It's over 86 degrees outside, the sun is beating down relentlessly, and there's little shade in front of the State Office for Health and Social Issues, which is now the first point of registration for refugees coming to Germany. There are roughly 500 other people waiting to be registered too. They line up to take numbers. There's no water and little food.

My boyfriend and I show up to the office in response to a call by the organization Moabit Hilft, a neighborhood initiative that aims to help incoming refugees with their daily needs. We have brought things from the supermarket to give out to those waiting — diapers, water, cookies.

It's there that I first see Mohamed. He's running around incensed, his face and one arm red. I try to ask him what's going on and he points to the police nearby, making a gesture like he's using a spray bottle. There has been an altercation between the refugees and security people, and when the police were called in they tried to calm the situation by using pepper spray. Mohamed got sprayed. He points to his daughter: "Her too." Rushin rubs her eyes and cries silently.

Seeing Mohamed, his wife, and their two kids reminds me of how we fled Rwanda — my mother and her three small children — after our family and friends were killed in the genocide against the Tutsi in 1994. I can't even begin to imagine what their journey to Berlin must have been like.

“I thought Europe was different. But they don’t want us here either.”

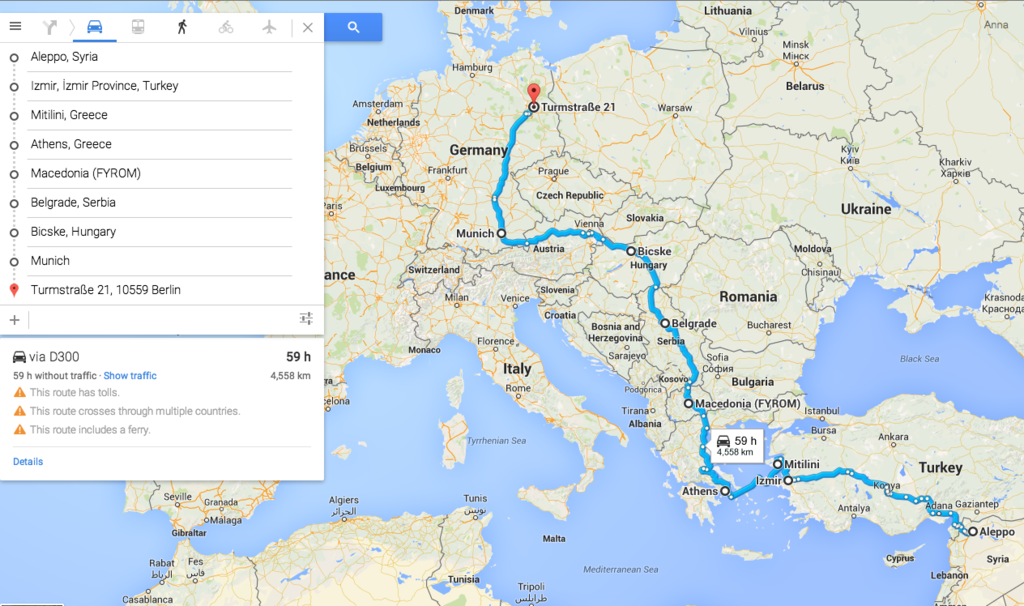

I speak no Arabic and Mohamed doesn't speak English, so it's hard for us to communicate. I ask a friend who has come with us to the State Office to translate and she helps. Mohamed tells us how Roqa had to watch as her parents were murdered. I can see how hard it is for him to talk about it and don't ask him any more questions. Mohamed tells us about the bombs that fell on Aleppo at night, how his family decided to flee. "It is better to die at sea than from a bomb," he says. Tears choke his voice as he describes the journey by inflatable raft from the Turkish city of Izmir to Greece: "'Two hours straight ahead and then turn right to Greece,' they told us."

In the boat ahead of them the engine died.

They were lucky. Their boat, carrying 30 adults and 10 children, made it to shore. The boat ahead of them had its engine die; Mohamed and his wife never learned what happened to those on board.

Once they reached Greece, a Dutch family let Mohamed, Roqa, Rushin, and Reema live in their summer house. From there they went to Macedonia, and from there to Belgrade, the capital of Serbia, and then they set out on foot for the 185-mile walk to the border with Hungary. Mohamed describes sitting in a circle with other refugees for three hours. Serbian border guards relieved themselves next to where they were sitting, he says.

I'm fighting back tears when Rushin suddenly interrupts her father, saying: "I thought it would be different in Europe, but here too they don't want us. Here too they want to burn us." Now her parents are crying as well. I beg them to come to stay with me, at least for the night. They're afraid they won't be registered, but I assure them the State Office is closed over the weekend and that I will bring them back to it on Monday. All of a sudden dark clouds appear and it starts getting windy. Mohamed looks at his wife.

A little while later we're sitting in the car and driving from Moabit to Friedrichshain, passing The Chancellery and Friedrichstrasse — a sightseeing tour through a city that won't welcome them. They're tired. The children are asleep, and Mohamed and Roqa look out of the window and speak quietly to one another. They've known each other for 14 years, they will tell me later.

In my apartment I give them towels and make their beds. They shower. I call my mother and tell her about my guests. We remember how we fled from Rwanda, 21 years ago. On the way to Uganda a man took us in and let us sleep and shower and after a few days we felt human again. I was 5 and remember to this day how relieved my mother looked. She smiled — something I hadn't seen since my father was killed.

“We came here because wanted to live with our daughters in peace.”

While my guests shower I go shopping with my boyfriend for a second time. We walk next to each other. I think about how unbreakable the bond must be in a family that has lived through all of this. Mohamed and Roqa will tell me later: "We came here because we wanted to live with our daughters in peace: no war and children that can go to school and can play in the street."

On Facebook I ask, "Does anyone have clothes for children and two adults?" The response is overwhelming, and a woman brings us a travel bag with clothes, colored pencils, shoes, and toys. Roqa cries when she sees the bag and the girls model their new clothes. When I send the woman a picture, she says, "I have more if you need it."

On Saturday, we sit together and eat omelets and drink tea. The girls try to teach me Arabic and Kurdish. Reema's green eyes beam with pride when I pronounce a word correctly. We laugh when Rushin and Reema make faces. Later, Roqa will tell me that Reema had an operation on her head in Turkey. She carried the injury with her from Aleppo. The bombs hit at night, and the family sought shelter in the kitchen and bathroom. When they detonated, Reema's head slammed into the sink. Since the operation her left eye has been giving her trouble.

We don't talk only about boats and bombs. One day, we are sitting in my kitchen again. Mohamed and Roqa ask me why I haven't married my boyfriend yet. "How long have you been married?" I ask. Mohamed pauses and says, "For nine years." Roqa looks at him reproachfully and corrects him: "It's been 10 years."

We laugh.

"If you want to be Princess Anna you have to have blue fingernails," Reema tells me. "Queen Elsa has red fingernails." We are sitting on the couch and waiting for our fingernails to dry. Frozen is playing on the TV. The two of them sing and I am fighting back tears again; Rushin says, from time to time, "I love you." I am her big sister and I have to promise not to forget her, she says.

A week later I visit them in an emergency refugee shelter in the Berlin neighborhood of Karlshorst. They are doing well but are apprehensive. The State Office for Health and Social Issues is housing them temporarily and they don't know where they will go next.

"You can't enter," a security guard tells me as I walk up to the big gray building, adding that a new group of refugees had just arrived. Mohamed and Roqa come outside. From there, they show us their room, on the fifth floor.

A week later they're forced to leave, to make room for new refugees. I have to call eight hotels and hostels in Berlin before finding one willing to take in the family. One hotel, the Ibis in Neukölln, told me it was its policy not to take any refugees — even though the German government pays for their stay.

Now, 17 days after they arrived in Germany, Mohamed, Roqa, Rushin, and Reema are living in a hostel in Neukölln, southeast Berlin. They have a small apartment within the hostel; another family from Syria lives on the floor below. It's small but comfy, with a little kitchen and a small bathroom, and they can wash their clothes and hang them in the courtyard, where Reema and Rushin like to jump around. "Why don't you have blue fingernails anymore?" Reema asks.

Half an hour later we are sitting on the leather couch in the hotel's reception area. "The couch reminds me of the inflatable raft we travelled to Greece on," Reema says. I don't know what to say.

This post was translated from German by Ian Bateson.