Nedal and I meet in an overcrowded café in Berlin. It's our second meeting. Over cappuccino and coffee we begin discussing the weather in German. How it's getting colder every day and the rain seemingly won't stop. He turns quiet as I ask him about his family. He's worried — there was a car bomb attack in his hometown of Hassakeh. Twenty people died and another 40 were injured. Apart from his youngest brother, Majid, his whole family still lives back in Syria.

Nedal was born to a Christian family just shy of three decades ago in Hassakeh, in northeastern Syria, close to the Turkish border, growing up with three brothers and a sister. Nedal's father owns a small shop; his mom is a school manager. He remembers his childhood as being really happy.

While working for a medical company to finance his studies at the university in Aleppo, he realized he didn't want to practice law after all. Instead, after finishing his studies, Nedal wanted to start a coursework to become an orthopedic technician. But the Syrian military interfered with those plans — Nedal, like all young men, is supposed to join the army after his university studies. He refused. Nedal also posted regularly on Facebook about his opposition to the government, despite his fears that it would end badly for him.

A friend invited him to Tunisia in 2011. Just days he before he was supposed to leave, the police came looking for him because of his rejection of the army. Luckily, he wasn't home that day. The minute his family told him what happened, Nedal decided to leave Syria. Shortly after his departure to Tunisia, his brothers were summoned by the police to explain Nedal's Facebook postings.

Tunisia was a place where Nedal felt he could start a new life — he finished his orthopedic technician course; he fell in love. He found a job with a German medical company that specialized in his field. From time to time, he got to assist his colleagues in difficult surgeries.

But despite his successes, Nedal was increasingly frustrated in Tunisia.

He worked, paid his bills, but still hadn't received a residential permit form the Tunisian government. His hopes for the country had evaporated.

It was then that he heard from his brother, Majid. Majid managed to flee Syria and was in Turkey, he said. The brothers decided to meet up. Reunited after three long years, the brothers chose to leave Turkey and seek a better life in Germany. They managed to cross the border into Greece with two other Syrians, registering at the police station in a small Greek town.

Instead of registering them as refugees, the Greek authorities threw them in a cell and took away their phones. They came to find them in the middle of the night and the group of four was forced to board a military boat that took them over the Maritsa River and back to Turkey. Three weeks later, a group of Syrian refugees would drown in that very river.

The soldiers spoke in English, and even a few words in German, Nedal remembers. (He doesn't believe they were actually Greek.) The soldiers led them back into a forest with wet clothes and no food, before throwing their phones at them, most of them drained of power. Cold and completely disoriented, the group tried to make their way out of the forest. With the help of a tiny Bic lighter they managed to make a small fire. They spent one night in that forest, leaving the next day. After a long six-hour walk, they were caught by Turkish officials, who took them to a camp in the city of Erdine. After a night in Erdine, the defeated group headed back to Istanbul.

"I thought that I was going to die."

The brothers stayed in Istanbul for two months. Nedal was frustrated but he didn't want to give up. He opted instead to try again — alone. He didn't want to put his brother's life at risk again. He didn't want his mother to mourn two children if it didn't work out.

Nedal left on Nov. 11, 2014, from Mersin, a city in the south of Turkey. The plan: Take a boat to the Italian island of Sicily and then continue to Germany.

He spent eight days on a small boat with about 250 other passengers. The weather worsened increasingly, and on the seventh day, the engine of the boat stopped working. "I was pretty sure I was going to die in that moment. I just wanted to go to Germany to live," Nedal says quietly.

Their boat was found and saved by Italian coast guards, who put the boat on an American cargo vessel that brought them safely to Sicily. Nedal has been an atheist for 15 years, and he doesn't believe in luck either: "Something happened that day; I can't tell you what it was but it was strong."

"This was one of the most humiliating situations in my life."

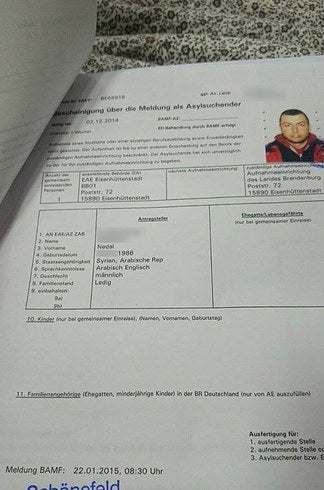

From Sicily, Nedal went on to Rome, then Milan, before taking a train to Munich. From Munich, he arrived in Berlin on a cold Friday in the end of November 2014. He sought out the police station in Berlin-Spandau to register as a refugee. They told him that he didn't look like someone who needed help. He was waiting with another young man from Algeria. After two hours, the police looked at their documents and took them to a bigger police station to register.

The two were put in a cell and made to wait for two hours. It was then, alleges Nedal, that a policeman arrived and told them to strip. Nedal removed everything but his underwear; the policeman insisted that they needed to go too.

"Is it necessary?" Nedal asked.

"It is the law," the policeman responded.

When asked if this is part of the usual routine, Stefan Redlich, press officer for the police in Berlin, said this to BuzzFeed Germany: "Asylum seekers are searched but usually not forced to take off all their clothes, although there are exceptions to the rule. For example when they act suspicious."

The police never told Nedal why he had to take his clothes off. "It was one of the most humiliating situations in my whole life." Nedal tells me today.

The police officers also took his fingerprints and his Syrian passport and sent the two men to a refugee center in Berlin. Nedal doesn't remember where exactly. "I didn't know my way around Berlin at that time." They spent the weekend at that center and left on Monday at 4 a.m. to go to the Berlin State Office for Health and Social Services, which has been in the news in the past couple of days due to being overwhelmed by the number of refugees coming to Germany.

"The hotel is full of immigrants and foreign-looking people."

At 10 a.m., after waiting for six hours in the cold, Nedal received a document telling him which shelter to go to. He was sent to a center in Eisenhüttenstadt, a small town southeast of Berlin that borders Poland. It is the same refugee center in which a refugee from Mali hung himself in May 2013. In Eisenhüttenstadt, he lived with 300 other refugees in a gymnasium. After two weeks, he was transferred to another center in Frankfurt an der Oder, a city in the state of Brandenburg, just an hour outside of Berlin. The conditions were a bit better there; only seven other men shared a single room with him. The refugees received documents that in theory allowed them to get a checkup. But in practice, not many doctors were willing to take care of them.

Another two weeks later, he was transferred to Berlin-Hoppegarten. There he shared a room with two other men in a hotel that is partly being used as a refugee emergency shelter. Later on, in February 2015, someone will post the following review about this hotel: "The hotel if full of immigrants and foreign-looking people."

In April 2015, Nedal had his court hearing in Schönefeld, where it would be decided whether he could stay in Germany or not.

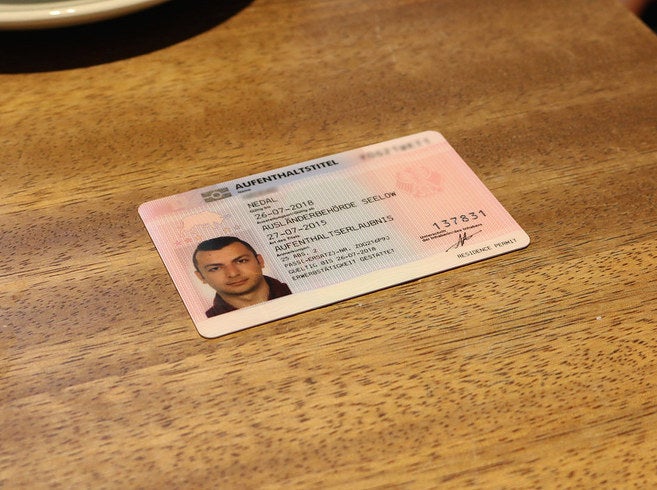

On July 27, nine months after Nedal set foot in Germany, he finally had certainty: He was allowed to stay — at least for the next three years.

"I didn't come here to live off benefits!"

Nedal is only allowed to work two hours a day because he is still studying German. As soon as his language skills are good enough, he will be allowed to work full time. For his dream job as an orthopedic technician, his German will have to be fluent. His law degree is not accepted here in Germany, he tells me. I ask him what he plans on doing if his orthopedic technician course is also not accepted. "I'll start all over again, then," he responds.

"My dream is to found my own company one day and give people a chance. I didn't come here to live off government benefits!"

He has been crashing at a friend's for a while now. Finding an apartment has been quite a struggle but he remains optimistic about it.

"We don't need pity, we just need a chance at a normal human life."

Almost a year after Nedal arrived in Germany, he tells me: "No country in Europe really wants refugees. But where else are we supposed to go to? We are normal people.

"We don't need pity, we just need a chance at a normal human life. Syrians especially are proud folks. First Assad and ISIS took away our dignity and now police officers at European borders."

"Only the sea will take us without a visa."

Nedal tells me that his brother Majid, who he left back in Turkey, made it to Germany a month ago. He starts showing me pictures of his family on his phone, including his sister's wedding last year. He tells me that she is pregnant and is having her first child in a few weeks.

"I am missing out on all these important moments of my family. The worst part is that I don't even know if I'll ever see them again."

Nedal's father is really sick and Nedal is trying to find a way to help him get to Germany. But getting a visa and coming to Germany safely is nearly impossible for him.

"Only the sea will take us without a visa," he says.

Update

"Asylum seekers are searched as a rule during the recording, but not stripped. In exceptional cases, but that can sometimes happen. For instance, if they behave suspiciously," said Stefan Redlich, spokesman for the Berlin police, to BuzzFeed Germany after this article was published.