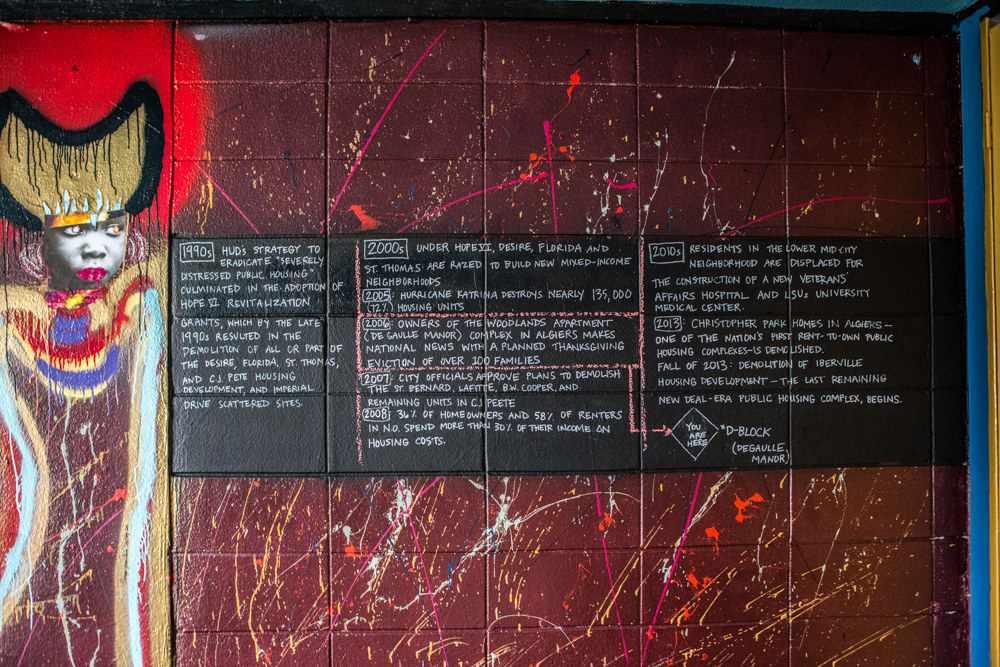

Over the past two months, an unheralded public art project in New Orleans has morphed into arguably one of the most powerful, provocative, and ambitious civil rights statements in this city's history. Housed in an abandoned apartment complex in the low-income Algiers neighborhood, Exhibit Be initially wasn't even supposed to last more than a day. But this weekend will be its last; the dilapidated buildings infused with painted tributes and installations will likely soon be buffed or destroyed.

“It's a wrap,” said Brandan Odoms, also known as Bmike, the curator of the project. “I haven't had the moment to really witness what's happening because I'm constantly in it. One day I'm going to sit down and really think about the beauty and the singularity of how this all happened by chance.”

It happened by chance earlier this fall when property manager Bill Thomason caught Bmike illegally painting a Tupac mural in one of the five buildings at De Gaulle Manor, a complex built in the 1960s that had been run down and eventually abandoned post-Katrina. Instead of calling the cops, Thomason made Odoms a proposal.

“I've been looking for you,” Thomason, 55, said. “I'd like to see if we can do something together.”

Soon thereafter Exhibit Be opened and has hosted car shows, poetry slams, dozens of school groups, myriad photographers, artists, and locals, most of whom heard through word of mouth. It's also been interactive; the kids who have come through the space are asked to paint and leave their mark.

On Monday, Jan. 19, Exhibit Be will close by hosting a block party; rappers Dead Prez will be performing live, there will be food trucks, marching bands, and people will celebrate. Before it's ghosted, here are a few of the stories and images from this uniquely New Orleans project.

The lure of painting a five-story building is what captured MEEK's attention. A graffiti artist here for 20 years with the longest-tenured crew in the city, MEEK's instinct was to shun something that would be so public and so easy — breaking part of graffiti writers' unwritten code. But MEEK has known Bmike for a while and wanted the challenge of the scale. His piece on Ferguson protestor Edward Crawford tossing back a police tear gas canister is the first you thing you see when walking through the Exhibit Be gates. It took three days to paint his version of St. Louis Post-Dispatch photographer Robert Cohen's iconic photo. “A lot of the big pieces [on the other buildings] were sanguine; I wanted to paint a piece of defiance,” MEEK told BuzzFeed News, “that represented the current state of America.” Like all of the 30-plus artists, he will get little to no compensation. “I hope it creates more opportunity for the artists to create more murals in this historic city.”

You can't lead the people if you don't love the people. You can't save the people if you don't serve the people. —Cornel West

Bmike, 29, has been a well-known artist in this city for years. In July 2013 he created a similar project in Florida housing projects, but that wasn't open to the public. Exhibit Be has been open every weekend free of charge to the general public; on weekdays Bmike's been coming nearly every day to host school groups, which he charges a small fee. He uses that money for docents Lana Meyon, 33, and Lydia Y. Nichols, 22 (pictured above). While Thomason initially opened the space, Bmike has put most of the money into it, posting the event insurance, the initial $3,000 round of spray paint, the porta-potties, security, and anything else. (He's also had a local businessman donate money). Now it's closing due to money and bureaucracy — the site is supposed to become a sports complex, but its future is tied up in politics and grants. “Our thing has been to preserve the integrity of what all these artists created and what was accomplished,” Bmike said, “and not get muddied by all the politics of what's going to have to happen to this space moving forward.”

Be a change that can rebuild a broken city! The storm is over.

On a cold mid-January morning, former Black Panther Malik Rahim stood beside a life-size mural of his face accompanied by the words THESE ARE OUR HEROES. At 65, he had just shown up on his bicycle unannounced and began giving a history lesson to a group of black high school kids.

“We must learn our history,” he said to the group, pleading with them to get an education, to be self-sufficient, to not become a statistic. After, two girls turned to each other, “Let's give him a hug.” Instead, they each posed for a photo. Rahim has spent his life fighting for fair housing. He stayed in the city during Katrina, fought the flood. “No one will accept you as an equal if you come begging,” he told the kids. “A beggar is never equal.”

Displaced New Orleans.

Taylor Ambeau, 17, returned to New Orleans recently; she grew up in the 7th Ward but had been in Georgia the last nine years. Her mom's a nurse, and Taylor should have graduated in December, but she wasn't ready to leave school yet. She said if she can't play basketball or soccer she'd like to be a nurse in the premature baby ward, same one her mother works. Ambeau asked me lots of questions. I told her I just moved here from New York City. She asked me how it felt; I told her it felt like home. “That's kind of how it is here,” she said. “Anywhere else feels different, like you're not in America anymore.”

"Everybody knows Tupac, but I encourage you more so than listening to his music to watch his interviews," Bmike said to a group of students on a tour earlier this week. "To me his interviews are way more stronger and powerful than his music. In his energy you can clearly hear what he was trying to accomplish. And understand the tattoo THUGLIFE is an acronym. Look it up. Learn it."

“I'm her plus-one,” Joshua Combs, 27, said. He had come here with Rubi Brown, 26, who said she had heard about the project from a friend. She didn't know much about it, only that it was in the West Bank, a poorer part of the city about 10 minutes from downtown New Orleans, where they had just purchased their hand grenades. Both locals, Brown and Combs came on a whim and were shy about being photographed with their glowing neon-green touristy drinks, fearful of sending a mixed message that they weren't appreciating the depth of the experience.“It's great to see people stand for a cause, to look at art,” Combs said. “It's not just black people here, it's blacks, whites — all races.”

We stand on the shoulders of giants.

The bus for Accelerated High School was leaving and a teacher was urging his students to get on because pizza was waiting back at the school. Just then China Mohamed, 17, walked up to me and asked if I worked for a newspaper. She said she was once a photographer, and pointed toward her art. She read out loud what she painted: FREE MY MOM, her last words about her imprisoned mother. “So everything I'm doing, I'm kind of doing it for her,” Mohamed said, adding that she's in the middle of writing a book. About? “My life and everything that happened and how I ended here. It feels good to know everything I've been through, that I actually made it. It makes me proud of myself.”

The Country Day School from nearby Metairie recently brought a busload of high schoolers here, many of them looking as if they just stepped out of a Brine catalog. The teens gathered in the yurt-like structure that is filled with murals of black history icons Bmike painted. Gil Scott-Heron, Biggie Smalls, Harriet Tubman, Radio Raheem, Maya Angelou, Huey P. Newton, Fred Hampton, MLK are among those on the walls. Bmike takes all the tours through there, giving personal anecdotes and history lessons for most of his pieces. Briggs Ham and classmate Wilson Grant, both 16, stopped to take rapper Biggie's photo. “I love it,” Ham said of the exhibit (pictured above). “Being able to reflect on so many different people's artistic ideas — it's about suffrage and remembrance. It's great.”

I freed a thousand slaves, I could have freed a thousand more if I only they knew they were slaves. —Harriet Tubman

Kenneth Murdock, 17, stood away from the pack, looking disinterested and on the defensive when Rahim and Bmike addressed his classmates. But Murdock had been listening. He approached me toward the end of his tour and asked me to look at what he painted. His painting read LIFE IS ME in orange, his initials and neighborhood tagged at the end. Murdock said that on the bus over they were talking about how they'd probably learn about the Black Panthers, “how it all started,” he put it. “It's something to see. It might change a lot of people's views,” he said. Why? “It may help them know what they stand for and who they are and what they can be.” He blinked a hint of emotion. Is that what he was feeling?

Murdock took a long pause as he surveyed the courtyard. “I wish I knew how to draw and paint.”