Web publishers are in a tough spot these days. As largely ad-supported businesses, they've come to rely on traffic funneled to them by social platforms like Facebook. In doing so, they've cultivated a dependency on companies that have no real allegiance to them, companies that can dramatically affect their traffic and revenue with even the simplest of platform tweaks.

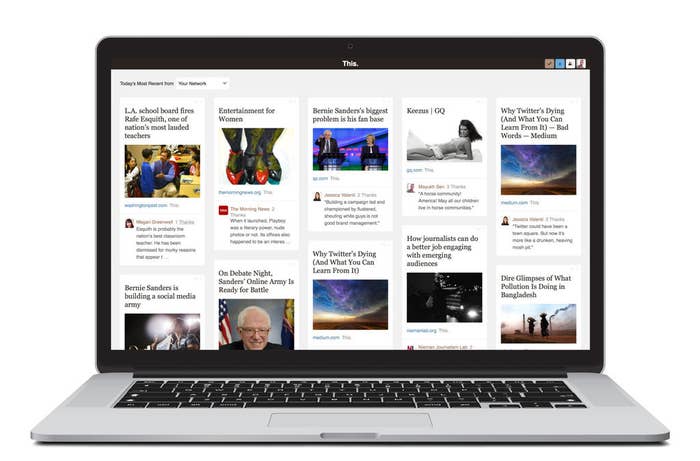

Andrew Golis, an entrepreneur who has served as an editor, entrepreneur in residence, and general manager at media companies such as PBS, Yahoo, and The Atlantic, thinks he's developed a social network that's better for publishers. It's called "This," and Golis is now taking it out of beta after nearly a year of experimentation.

This, which amassed a membership of around 12,000 users via word of mouth invitation, is now open to all.

"Media has never been a bigger part of people's daily experience on the web and there's never been more good media on the web," Golis told BuzzFeed News in an interview. "But media discovery on the web is still fundamentally broken. I think that's a baffling paradox that no one is paying enough attention to."

Golis' solution is to limit the volume of content shared on his network to a single link per person, per day. Doing so incentivizes the sharing of great work, he said.

"I don't ever see the kind of typical aggregated clickbait floating around on our site," Golis said. "That fundamental premise has been proven out a thousandfold."

The one link per day constraint isn't new; it was in place throughout This's beta. Now that the platform is public, Golis is adding another tweak. Next month, This will introduce Link Rooms, discussion threads built around specific links that can be viewed by those who share them. The goal is to bring people together around common interests in content — not around people they know.

This, incubated within The Atlantic, is being positioned as the anti-Facebook, which Golis said is structured to connect friends and families, and therefore incentivizes the sharing of content meant to deepen those relationships. That content, however, doesn't always showcase the best work of the publishing companies that produce it.

"The incentives set up for the kind of media that flows through that system are not the same thing as the kind you would set up if your first and foremost goal as a network was to connect people to the media that really moves them," Golis said.

Social platforms also incentivize volume, he added. The more you tweet, the more followers you rack up, Golis said, arguing that frequent tweeting inevitably leads to a decline in the quality of links tweeted.

Golis' comments come at a time of unprecedented power for social platforms. Not only do these platforms send significant traffic to publishers' websites, they're also hosting publishers' content and cutting them in on the revenue. Think Snapchat Discover; Facebook Instant Articles; Apple News.

Some of these platforms are also running large "off-platform" advertising businesses, where they sell ads on websites across the internet targeted with the data they collect.

These developments are not necessarily bad for publishers (Full disclosure: BuzzFeed is partnering with some of these companies), but it's still a lot of control to put in the hands of others.

"What we're seeing with Facebook and Apple is an attempt to eat the web," Golis said. "I think that's bad for consumers because it makes the content that consumers are going to see less diverse, less surprising, more corporate, more about the deals that are made in biz dev meetings than about the organic weird wonderfulness that the web has always been about.

"And obviously it's bad for publishers inasmuch as it sets up a world in which they are subsidiaries and/or just distributors on someone else's network."

Golis's proposition is simple: Instead of trying to create stuff that's widely read on Facebook, simply do your best work and trust that it will be shared and read.

"The better the work, the more people will find it," he said.

An idealistic notion, perhaps. But that's not stopping Golis from trying.