In 2013, New Orleans police arrested 34-year-old Quincy Briggs during a sweep of a suspected drug-dealing organization. Earlier this year, he was convicted of dealing heroin. Because Briggs had two prior felony convictions, he got 50 years in prison.

That lengthy sentence is commonplace in Louisiana, where state laws increase punishment for each of a defendant's prior felony offenses, no matter whether the felonies were violent or not. These sentences help explain why New Orleans has for years had the highest incarceration rate of any city in America, and Louisiana has the highest rate of any state, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. At a time when both states and the federal government are reconsidering lengthy sentences for nonviolent drug crimes, Louisiana has bucked the trend.

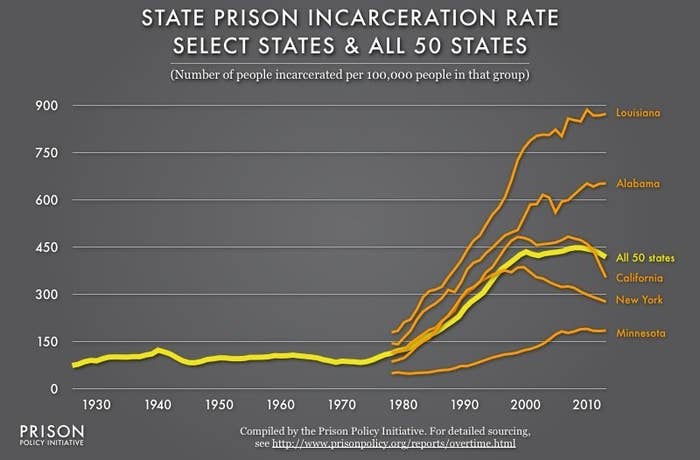

While state prison incarceration rates across the country have remained steady over the last 15 years, at around 400 inmates per 100,000 people, Louisiana's rate continued to rise, from under 800 to nearly 900 inmates per 100,000 people, according to data compiled by the Prison Policy Initiative.

In the decade since Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans has tried to ease punishments for drug crimes. The city recently passed a bill that prevents the District Attorney's Office from charging first-time marijuana possession as a felony, and before that an ordinance asking police officers to issues summonses to, instead of arresting, people caught with small amounts of weed. Over the past decade, the number of arrests has plummeted, from around 140,000 in 2004 to around 30,000 in 2013, and so has the number of inmates in the county jail, from around 6,000 to around 2,000. City leaders have touted these stats as part of New Orleans's successful rebuild in the years since the storm.

But defendants facing serious time deal with state laws, and most of those convicted of felonies end up in state prison. And so despite local and federal efforts, Louisiana defendants continue to face decades-long sentences for nonviolent drug crimes.

Before his 2013 arrest, Briggs had had a previous drug-dealing conviction and an illegal gun possession conviction on his record (an illegal gun possession is not considered a violent crime under federal or state sentencing guidelines). This third felony conviction meant that he faced a minimum of 33 years in prison.

"It's outrageous," said Greg Carter, one of the lawyers who represented Briggs. "It keeps our jails full. You just throw people's lives away."

In the '80s and '90s, while states across America were getting "tough on crime," Louisiana became among the toughest. A second felony conviction makes a person eligible to be sentenced as a "habitual offender," which makes sentences even longer. While a first cocaine possession conviction brings a maximum sentence of five years in prison, a second brings a 10-year max. Three drug convictions can make a person eligible for life without parole. Three nonviolent convictions with sentences of 12 years or more can lead to automatic life without parole. According to a 2012 New Orleans Times Picayune investigation, more than 300 inmates in Louisiana are serving life without parole even though they haven't been convicted of a violent offense.

"It's one of the reasons why we have the highest incarceration rate in the world," said Steve Singer, a law professor at Loyola University.

There is little judges can do in the face of a potentially disproportionate sentence, other than hand down the minimum.

"People have the impression that judges are all powerful, but we're not," said criminal court judge Arthur Hunter. "We have to work within the system."

In one case, police stopped Barnard Noble, a 49-year-old father of seven, while he was riding his bike in 2011. They found 2.8 grams of weed on him. He was convicted. It was his third drug possession conviction, which placed him under the state's habitual offender law. The judge sentenced him to the mandatory minimum: 13 years in prison.

In another case, 42-year-old Daniel Miller was arrested in June after a police officer saw a syringe in a car he was riding in. A liquid in the syringe tested positive for heroin and cocaine. Miller had an armed robbery conviction in 1992, a bank robbery conviction in 1998, and a marijuana and cocaine possession conviction in 2009. Because of those priors, Miller faces a minimum of 20 years in prison for his latest charge.

"We still have a deeply broken system," said Mary Howell, a civil rights lawyer in Louisiana. "It was broken before Katrina and it was broken after Katrina."

And each day more and more defendants enter the system for the first time, joining a growing list of people eligible for stacked sentencing.

At 7:45 one June morning, nine people sat up and down the courthouse steps waiting for the heavy doors to open. They hoped to get their court-mandated drug testing done early, before work or summer school or whatever they had planned for the day.

Two college students, Steve and Jack, were among the nine. They had been caught with two others smoking weed in a car parked in front of a friend's house in the Lower 9th Ward. The cop had pulled up behind them, lights flashing, jumped out the car, gun drawn, shouting at them, they said. The officer wrote them summonses and they were each charged with a misdemeanor. They both had clean records before this, and so the judge let them off with three months of drug tests and around $500 each in fines and fees. But now that they had passed into the system, they understood the stakes. Any future weed possession arrests would be felonies.

"We get caught again," Steve said, "we going to the big house."