Bright students from disadvantaged backgrounds need to start preparing to apply to top universities as young as 9 or 10, sixth-form teachers have told BuzzFeed News, as they revealed the barriers that keep Oxbridge a bastion of middle-class whiteness.

Students from richer backgrounds are 10 times more likely to apply for top universities than those from disadvantaged backgrounds, BuzzFeed News analysis of UCAS data has suggested.

In October, MP David Lammy revealed the lack of diversity of students at Oxford and Cambridge by showing that a number of Oxford colleges had not accepted a single black student in 2015, and that students from the south of England and London were much more successful in gaining entry to top universities than those from the north of England. Following Lammy’s disclosure, more than 100 MPs signed an open letter to the universities’ vice-chancellors calling for them to do more.

But BuzzFeed News spoke to state school teachers who said that while universities needed to take steps to teach a wider variety of people, some barriers start as early as primary school, more than a decade before students even apply.

As the debate over access continues, they shared their solutions, which include lowering university grade boundaries, teaching a “super curriculum”, and getting kids into the mindset to apply for elite universities when they are as young as 9 or 10 years old.

“There’s not an intervention early enough,” said Hetty Brown, a teacher at St Brendan’s College on the outskirts of Bristol. The college of roughly 1,800 students draws from across the city. “It’s a very comprehensive intake, so there is very low selection criteria,” she said, and students are from “really diverse and challenging backgrounds”.

“Research has shown that years 5 and 6 are critical for changing a student's opinion about higher-education participation,” said Brown, who praised the nearest Russell Group university to her college, Bristol, which is running a scheme introducing primary school children to the possibility of higher education.

Her thoughts mirror those given by university admissions tutors this month. Writing in Times Higher Education, Oxford admissions tutor Jonathan Leader Maynard said only “fundamental changes” to British state primary and secondary state schools would significantly widen access.

The teachers BuzzFeed News spoke to agreed that when it comes to going to Oxbridge, the scales are tipped in favour of privately educated kids.

Mouhssin Ismail, headteacher for the selective Newham Collegiate Sixth Form (NCS), said many state schools focus too heavily on preparing children for exams, while only addressing the skills for university application and interviews in their late teens. In contrast, he said, private school students are taught to interrogate information from a young age. “I wouldn’t be leaving it until 16, I think that’s often the problem,” he said.

NCS is in a deprived area of east London, yet a striking 99% of its students achieved A-C A level grades this year, 95% of its pupils won places at Russell Group universities, and the school celebrated nine pupils getting the grades to take up Oxbridge offers.

But it has been accused of using controversial methods: Schools Week reported earlier this year that NCS was one of several schools to tell some pupils they could not continue into the second year of sixth-form unless they achieved a C or above in their AS-levels. It told BuzzFeed News that there was an “expectation” that students should get these grades, but that this was applied with discretion.

Students at his school, Ismail said, are prepped with a “super curriculum” that aims to address the holes in the state school education. Kids educated privately are often able to draw upon a wide breadth of knowledge that his students couldn’t, he said. “Our kids are very good – ask them a question about biology or chemistry that’s on the syllabus, [and they are] brilliant, but [it's different if] you try to ask them about something in the arts, theatre, or something that is not in their cultural capital.”

His kids sometimes see Oxbridge interviews as being like those on The Apprentice or Dragons’ Den, with clear questions and answers, while in fact more depth of knowledge is needed, he said.

“You just have to look at the Eton College King’s scholarship paper,” he said. “There [are] questions on there that a 13-year-old at an independent school has to answer to get into Eton. They are almost A-level questions. That’s the bar that is being set.”

Ofsted, the governing body that inspects schools, shares these concerns. Amanda Spielman, the head of the body, wrote in a commentary in October that students from poorer backgrounds were being offered fewer subject choices, and a more intense focus on exams, than wealthier peers at GCSE level.

Spielman wrote that many schools, keen to get as many students as possible those coveted A-C grades, were shutting students out of a broader curriculum. “It is a risk to social mobility if pupils miss out on opportunities to study subjects and gain knowledge that could be valuable in subsequent stages of education or in later life,” she noted.

Brown also told BuzzFeed News that as many teachers were not Oxbridge graduates themselves, their ability to offer help for such a specific entry process could fall short despite their best efforts.

Ella Jefferys, who taught for two years at Kingsmead School in Enfield, London, agreed that during her time as a teacher she “definitely felt inadequate prepping students for Oxbridge interviews".

“Yes, I had all the resources,” she said, “but I had never sat one.”

Some teachers BuzzFeed News spoke to supported the suggestion in a report from the Sutton Trust in October that universities should lower the grade boundaries that disadvantaged students are set to be able take up their university offers. The trust said this could lead to a 50% increase in the number of pupils on free school meals admitted, and noted that “widening access to the UK’s most selective universities is an important means of increasing social mobility”.

Independent schools educate only 16% of students aged over 17, but just under 50% of those students achieve either A or A*s, according to 2017 data from the Independent Schools Council – a considerably higher percentage than the 26% of students at all schools that achieve the same grades according to government stats.

Brown argued that lowering grade boundaries is “absolutely critical” to expand access. She said although many of her high-achieving students had achieved good grades at GCSE, “they would have got 11 A*s in a really pushy, maybe fee-paying school, but because of the school that they come from … there are gaps in their grades. That all needs to be taken into account.”

Jeffreys agreed, saying the suggestion made by some that lowering grade boundaries would pull down the quality of elite universities was “bullshit”. Her students were just as “academically able” as someone from private schools, “and to be honest they probably know a hell of a lot more about what the world is really like”.

Brown – who went to Oxford – noted that the challenge was not just getting an offer from an elite university, but also achieving the grades required to take up a place. “Everyone thinks, Oh brilliant, they’ve got the offer, but [that’s] when they really get busy.”

Students from some groups are more likely to miss their predicted grades, with both Oxford and Cambridge noting a drop-off between students accepting places and actually attending, according to the Department for Education statistics.

But Ismail disagreed that entry requirements should be lowered. “I don’t think that should ever be done. For me, that’s a race to the bottom,” he said. “I wouldn’t lower the grade boundaries for kids because it’s a typical argument: ‘You only got here because you come from a low income, not because you’re bright enough.’

“At no point should we ever, in my view, reduce the entry criteria for kids from low income. The onus should be on us and the universities.”

In the background of all of these concerns is money. Funding at local level for state schools could not compete with the money poured into private ones, the teachers told BuzzFeed News.

State funding for 16- to 19-year-olds decreased by 14% in real terms between 2010-11 and 2014-15, according to the National Union of Teachers. Although the government announced in 2015 that it would protect funding for the next five years, the NUT said that given the current rate of inflation that still means a cut of around 8%.

The Sixth Form Colleges’ Association says that since 2010, colleges have lost around £100 million in funding. This has a tangible effect: By October last year, 66% of colleges had said they had dropped courses, narrowing the curriculum on offer to sixth-formers, and 84% reported larger class sizes.

The average spend on a teenager in a sixth-form college hovers at just over £5,000 a year, according to data from Institute of Fiscal Studies, down from a high of £6,000 in 2011-12.

“Honestly, I don’t think state school teachers always have the time and resources to support students who should be applying,” said Jefferys, who helped coordinate the UCAS applications programme at Kingsmead School in London. The academy, rated "good" by Ofsted, has more than half of its 1400-strong student body eligible for free school meals, and 51% speak English as a second language.

Her views were echoed by Brown, who said funding cuts meant some selective state schools got more funding while many ordinary schools with talented kids didn’t. “There is no money at all for any sort of cross-city provision for the gifted and talented students,” she told BuzzFeed News.

“It is about the government funding cuts having a huge impact, … often the more able students. Because teachers think, They’ll be all right. They are going to get an A. And you know what? An A isn’t good enough, because they could have got an A* and gone to Cambridge.”

She continued: “There is not enough time as a teacher. You have so much else going on, so many other pressures, Ofsted, a million things on a lesson plan that you have to put in place, that teachers do not really have the time to really focus on students.”

“Statistically speaking, there must be potential Oxbridge candidates in those very schools … [who] don’t even know that they have access to that opportunity, because the funding isn’t there.”

But even when schools have the time and money to help students bright enough for Oxbridge to succeed, they have to want to apply in the first place. The teachers agreed that students were discouraged when they saw a lack of diversity at top universities. Ismail said students from a deprived area like Newham, where his school is based, rarely see “people who don’t look like you, who are not from a similar background, or have similar beliefs or values” at such universities, “and I think that’s the problem”.

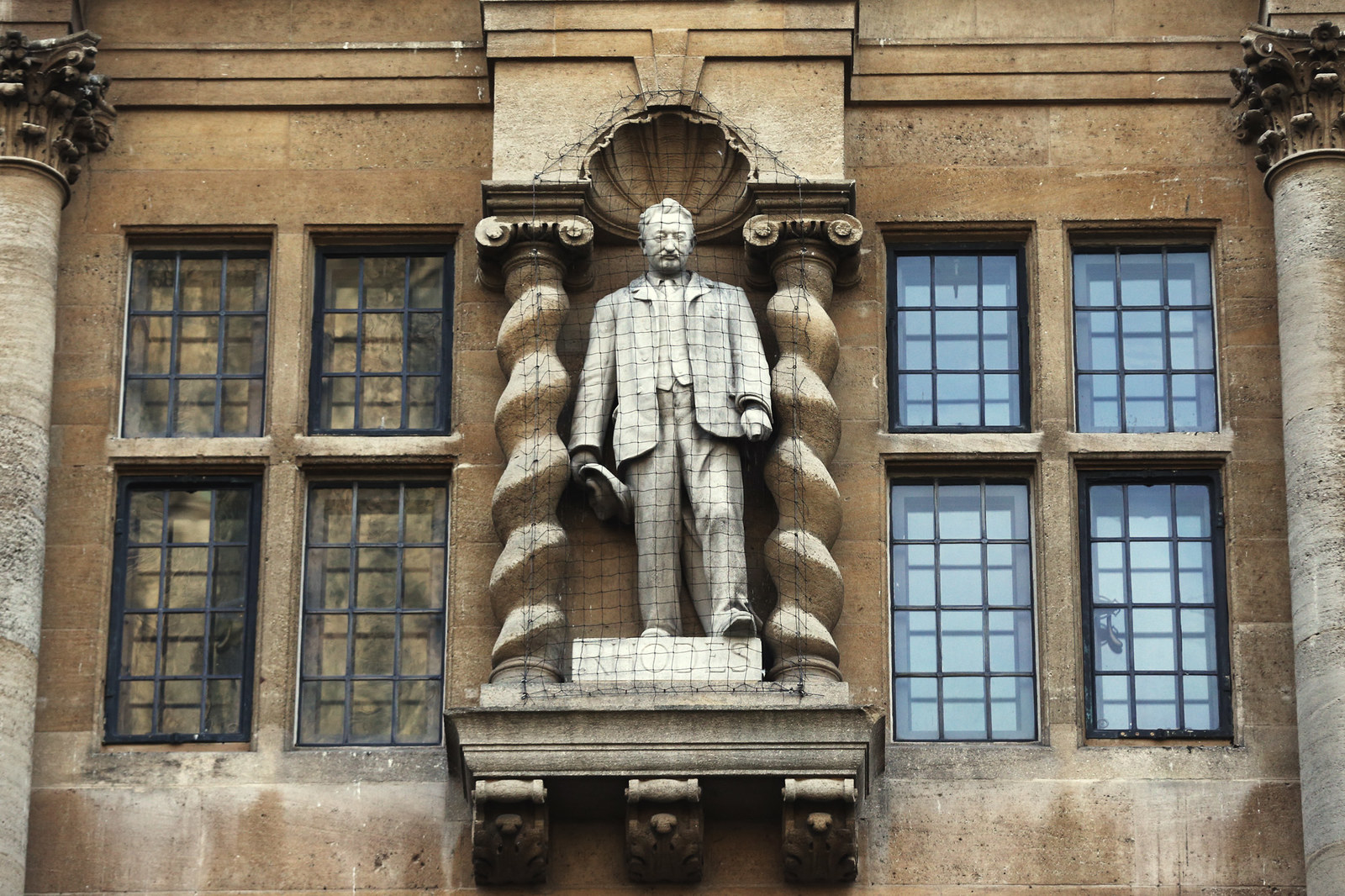

Oxbridge is problematic in the minds of many potential applicants, said Jefferys: “When you have a statue of Cecil John Rhodes on Oriel College how can you genuinely claim to be pro-inclusion and -diversity?”

The “Rhodes Must Fall” campaign – centred around removing a statue of the colonialist from Oriel College, Oxford – kickstarted a national discussion around the “whitewashing” of university environments and curriculums, which could be having a knock-on effect on applications.

Jefferys said she was aware of a number of students who “at least should have taken a shot” at Oxbridge but instead applied to the “much more popular” Imperial or UCL, where they felt they would fit in, and perhaps, she said, also because they were closer to their school in London.

Brown mentioned that she thought some students “psyched themselves out” of applying to Oxbridge after researching different universities. She said work is needed to address those “mental barriers”, as students “don’t think it’s the right place for them, or they don’t think they’ll fit”.

All the teachers BuzzFeed News spoke to felt the issue was one for both schools and universities to tackle. As Jefferys put it: “I don’t think it’s an either/or, I think it’s both and they are part of the same system.” They emphasised that until the imbalance between state and private was addressed, universities like Oxford and Cambridge will remain perceived as bastions of middle-class whiteness.

If teachers can help develop the culture in their schools, Brown said, towards one where “generations and generations of students, like in a middle-class-type environment, have been to university ... then you are beginning to shift things towards a more balanced society.”