Two Bangladeshi men seeking protection in Australia on the basis that they were gay and a de facto couple were subjected to highly personal questions about their sex lives in their interviews with the Australian government’s case officer, including whether they swallowed each other’s semen.

Documents obtained through freedom of information (FOI) reveal the list of questions the men were asked in their interviews at the then-Department of Immigration and Citizenship’s Sydney headquarters in 2012. Their protection visa applications were later rejected.

In the separate interviews of the men known as Applicant A and Applicant B, prominent strands of questioning focused on details of their sex lives, which the Refugee Review Tribunal later criticised as “intrusive” and unnecessary.

In the first interview, the departmental officer asked Applicant A whether he had sexual intercourse the night before and when he last had sex with Applicant B. The officer asked follow-up questions about the details of the intercourse, pressing Applicant A to identify exactly when they had sex, in which room it took place, at what time of day, and how long it lasted. “Was it all over within minutes? Or a longer period? 30 minutes to one hour,” the officer asked.

The officer then pressed for more details of the intercourse. They said: “So you gave him oral sex. Did he ejaculate? Ejaculate ... Did he reach a climax? Did he come?” After asking how long it took for Applicant B to climax, the officer said: “And then oral sex was given to you. Did you come?”

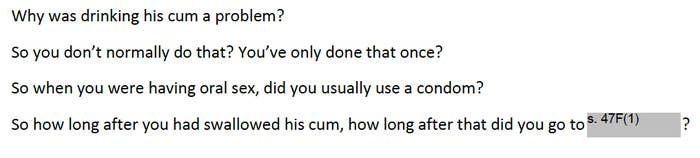

Towards the end of the interview, the officer inquired about an instance when the pair sought a sexual health check. The officer then asked this series of questions, apparently prompted by Applicant A’s explanation of why they sought the check:

The officer also asked for intimate details about the first time Applicant A had sex with Applicant B, and questions about their habits, such as whether they used condoms.

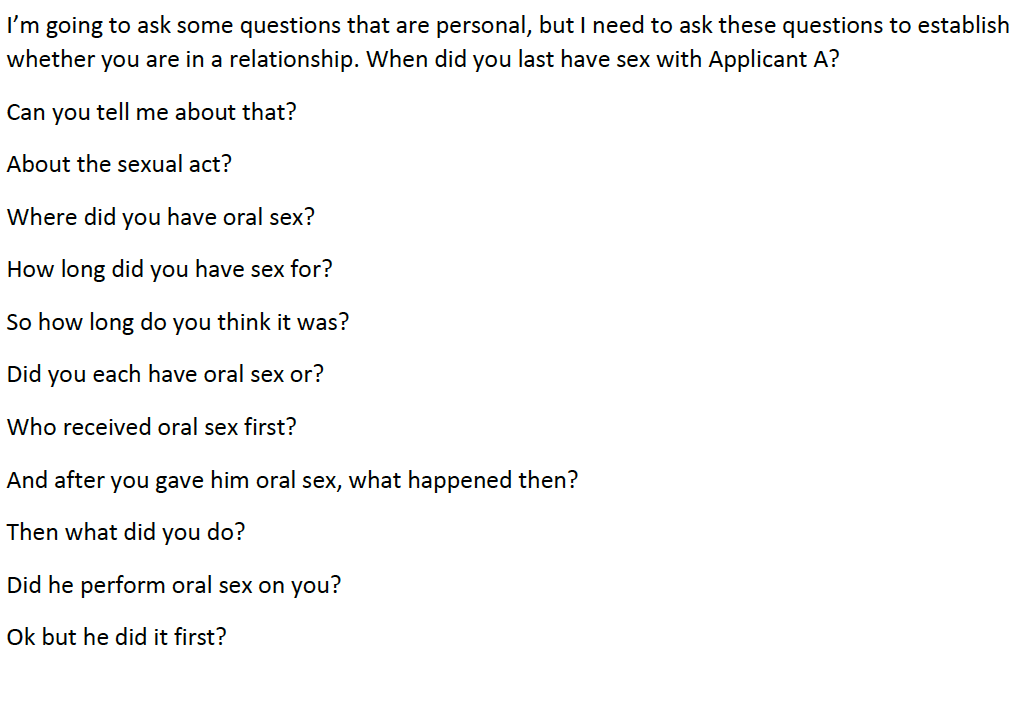

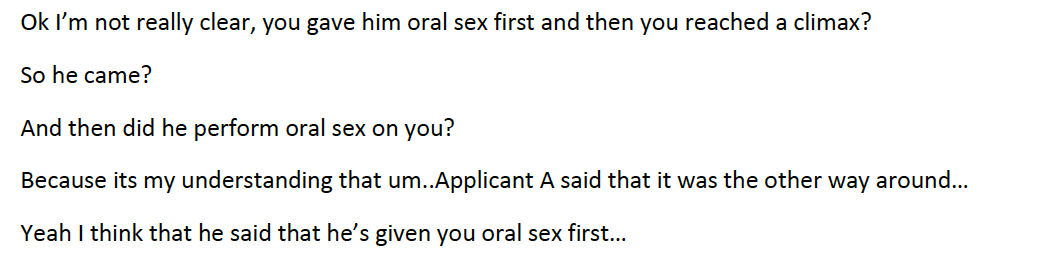

Later that morning, the same officer interviewed Applicant B, asking him similar personal questions about his sex life. Pressing for details on the last time the two men had sex, the officer asked how long the sex lasted, in what order the men gave oral sex, and whether Applicant A ejaculated.

Later, the officer asked Applicant B about a “sexual incident” between them that prompted Applicant B to go to a clinic. “I believe he said that um you ejaculated into his mouth,” the officer said. Earlier in the interview, the officer had asked three times whether Applicant B swallowed Applicant A’s semen.

The man was also asked whether a vaccination he received was for HIV or AIDS, whether he was circumcised, whether he had other sexual partners since first having sex with Applicant A, and whether he had sex the night before (between the questions “What time did you eat?” and “What size unit do you live in?”).

The officer also asked the men about various photographs of them, their relationships with their friends, and about various outings, including to Mardi Gras.

In 2014, the Refugee Review Tribunal overturned the decision of the officer to reject their protection applications, remitting the applications to the government. The tribunal members remarked on the “very intimate” questions, saying: “I found the questions intrusive and are not ones I have ever found it necessary to ask of applicants claiming to be homosexual.”

Anna Brown, incoming CEO of LGBTQI legal advocacy organisation Equality Australia, told BuzzFeed News that “this level of sexually explicit questioning is shockingly inappropriate, particularly given the applicants have a history of trauma and persecution based on their sexual orientation”.

“Comparable jurisdictions, such as the European Union, have banned questioning of this kind because it violates the applicant’s rights to privacy and human dignity,” Brown said.

Jaz Dawson, a PhD student specialising in queer refugee law at the the University of Melbourne’s Melbourne Social Equity Institute, told BuzzFeed News the interviews were “especially egregious” because the officer asked “humiliating questions about sexual practices, presumably in an attempt to catch the applicant out in a lie about how they have sex with their partner, in order to prove that they are not really gay” – questions which would not be asked of heterosexual applicants.

In an emailed statement, a Department of Home Affairs spokesperson acknowledged that some of the lines of questioning were “inappropriate and insensitive”, and said that “appropriate action was taken in relation to this case”. The departmental decision maker on the FOI request noted that the interviews were conducted by a single case officer, who had been “counselled about their conduct”.

Brown told BuzzFeed News that this was not an isolated incident.

“There are numerous examples of inappropriate sexually explicit and stereotypical lines of questioning in Australian tribunals and courts,” Brown said. “Ridiculously, there have been instances where gay people have been tested on their knowledge of Oscar Wilde or particular gay nightclubs on Oxford Street, and applicants have felt compelled to produce footage of sexual encounters to prove their claim.”

Decision-makers should focus instead on applicants’ “self-identification and exploring their personal narrative about the realisation and experience of their identity, including feelings of difference, stigma and internalised shame, and the fear of harm in their country of origin,” said Brown.

Australian NGO Kaleidoscope Human Rights Foundation developed a guide in 2015 to questioning LGBTI applicants, based on European and international best practice, which recommends a focus on sense of self, narrative, and life story.

The FOI request decision record stated that the department’s approach to interviews with LGBTI protection visa applicants had “shifted significantly” since 2012.

“Since 2012, the Department has significantly strengthened its guidelines, and provided additional training, on assessing LGBTI claims and conducting applicant interviews in a sensitive manner,” the spokesperson said, adding that the department was committed to “supporting LGBTI individuals throughout the protection visa assessment process”.

A document called “Assessing claims related to sexual orientation and gender identity” was released by the Department of Home Affairs under FOI in May 2017 (but not otherwise published). The document, which was described as providing “policy and procedural guidance” for assessing protection claims relating to sexual orientation and gender identity, states that it is “important that questions assess the credibility of the LGBTI but are also sensitive and not intrusive”.

“It is not appropriate for officers to ask applicants for details of sexual activity,” it says. The document recommends decision-makers ask applicants about experiences of self-realisation, any sense of difference or shame, experiences hiding their identity, exclusion from family or community, attempts to conform to avoid mistreatment, and experiences of past mistreatment. BuzzFeed News has sought clarification from the Department of Home Affairs on the status of the document.

Dawson told BuzzFeed News that the department only developed guidelines for the first time in the past few years, and that questioning had “no doubt” improved since then.

“The clear issue in Australia, however, is that of publicly available guidelines, training, and statistics on how the department seeks to improve its decision-making. Without transparency, it is difficult for civil society, media, and academia to provide oversight and evaluation of the department’s handling of these claims,” Dawson said.

The interview transcripts were released under FOI laws in September. Unusually, while the fact that documents had been released was listed on the department’s disclosure log, the documents were not made available for download. The department did not respond to a question about why this is.

The department declined to say whether the men were eventually granted protection visas.