“We grew up in that beautiful river,” says Nancy Yukuwal McDinny, as she sits cross-legged on the ground, painting. “Until the mine came and destroyed that river.”

McDinny, an artist, has spent her life in and around remote Borroloola in the Northern Territory. Sitting beside her more reserved husband Stewart Hoosan, she talks about the generations who have lived on Narwinbi, or the McArthur River, drinking water, and eating fish and the bush plums that grow alongside the river.

“But we cannot eat that anymore, because we don’t trust the river because of the McArthur River Mine,” says McDinny. “The big flood comes, it’s probably all poisoned.”

It’s impossible to imagine what the world will look like in the year 3037, but that’s when mining multinational Glencore says it will finally be safe to stop monitoring the site of its McArthur River Mine, 1,000 years after digging wraps up.

The open-cut mine — one of the largest zinc resources in the world, which also contains lead and silver — lies in the Gulf region, the traditional home of the Yanyuwa, Gudanji, Mara and Garawa peoples. The remote pocket of northern Australia is far from the Northern Territory’s urban centres, but an hour’s drive from the mine is the small, majority-Aboriginal town of Borroloola, which straddles the McArthur River.

As the mine approaches the end of a five-year process to approve its plan to stave off an environmental disaster of its own creation, many of Borroloola’s residents are afraid. Some are angry. Some are tired. Others are tired of people complaining. However they feel about it, their lives and futures are now bound up with Glencore — and whether it can fight off the environmental devastation that its mine threatens to wreak on the river.

Sitting in her parents’ front garden with her dogs at her feet, watching her kids play with a soccer ball nearby, Darilyn Anderson tells me in a quiet voice that she’s seen the rocks in the water of the McArthur River change colour — from a dark shade to a sharp white, as if something is burning. During the wet season, she says, the water turns orange and dark black, “sort of oily”.

The day we speak, there aren’t many people about — they’re out of town fishing. Like everyone else I meet in Borroloola, Anderson loves to fish, but she won’t eat fish from the McArthur River, choosing to travel over 100km east to the Robinson River or north to the ocean.

Anderson, a childcare worker, and her husband, Gadrian Hoosan, who is McDinny’s son and a musician and community spokesperson, are worried about the river. But something else is weighing heavily on the two of them.

They live at Garawa One, one of the four Aboriginal town camps dotting the outskirts of Borroloola’s main town. Borroloola’s population is less than 1,000, and its township is no feat of infrastructure, consisting of just a short main road, a handful of shops and cafes, a petrol station, a caravan park, a school and some government and services buildings on either side.

Still, it’s much flashier than the town camps. There, the roads are in poor condition, often unsealed, and with no footpaths. The streets have no names. The centrepiece of each camp is an old playground. Despite years of pleading from the community for new accommodation, the houses are ageing and in a state of disrepair, and they’re overcrowded. Some people live in sheds without power or water, built as temporary accommodation when a cyclone tore through in the 1980s. Rusty cars sit abandoned, windows smashed, a home for snakes and spiders. On one, the windscreen is peeling back like a bandaid. At Garawa One, the sewerage system frequently breaks down, and the water tank often runs out of water.

In April 2018, notices appeared in Garawa One and the neighbouring camp Garawa Two warning residents not to drink any water. Routine tests had recorded elevated levels of lead and manganese in the drinking water, and it wasn’t safe, according to the NT health department.

Hoosan and Anderson immediately thought the same thing — the mine was to blame. Although the government would lift the warning a few weeks later, insisting it had fixed the problem and that it had nothing to do with the mine, Hoosan and Anderson still believe their water is poisoned.

“The thing started to burn, all the smoke came across the road and you could smell it from Borroloola as well,” says Jack Green, a Garawa Senior Elder and a senior ranger. Like McDinny, he’s a painter who often makes art about the mine.

Green is usually outgoing and irreverent, but his voice is quiet as he recalls the time in December 2013 when a hill on the mine site started to spontaneously combust. The waste rock dump — the man-made hill where miners discarded dug-up rocks that didn’t contain enough minerals to extract — would continue to burn for over a year, sending toxic plumes of sulphur dioxide drifting into the air for years.

“It was really shock to everyone. We were really worried — some people might have asthma, we were worried for young kids and pregnant ladies,” Green recalls.

So why did the dump combust?

Glencore admitted in late 2013 that it had been using a flawed system to classify its waste rock and tailings, the latter of which is the waste remaining once minerals are extracted from rock. (Glencore has owned the mine since 2012, when it merged with Xstrata.) The company had said in 2012 that less than a quarter of the waste rock was potentially acid-forming, but in reality that number was higher, and much of the rest of the rock was still highly reactive. All up, the risky rock made up nearly 90% of the material.

“They just fundamentally got it wrong,” says Gavin Mudd, a mining expert at RMIT University. “It’s hard to imagine it could be stuffed up that badly in the 21st century, but it was.”

Reactive rock must be treated carefully, as when it meets oxygen in air or water a chemical reaction can be triggered that releases energy, causing extreme heat and smoke.

“It’s absolutely extraordinary,” says Mudd. “I don’t know of a mine site that’s had such a big waste rock dump in the base metal sector actually be so highly reactive like that.”

Alarmingly, the smoke and fire were evidence of a far greater danger, as the region’s water system was now at risk.

“There is a slow moving but high environmental risk that it could lead to the water system of that area being permanently contaminated, and destroying access to clean water and the livelihoods for communities in that area,” says Gillian Duggin, principal lawyer with the NT Environmental Defenders Office who represents, Green, McDinny and Hoosan, and other Aboriginal community members in and around Borroloola.

Reactive rock can cause acid mine drainage, and other kinds of toxic waste. Reacting with oxygen, the sulphide in the rock converts to sulphuric acid, dissolving heavy metals and leading to acidic, metallic water leaching from the rock. Rain can then carry this noxious brew into groundwater and creeks.

“There is so much acid being generated and so quickly, and so much heat, that the heat doesn’t have a chance to dissipate, so it’s just building up inside the waste rock dump,” Mudd says. “That’s why it looks like lava.”

Because the mine was unaware of how much risky rock it had piled on the waste dump, it hadn’t done the required work to protect the local water system. The result is a serious threat to groundwater and the McArthur River.

“The risk from the McArthur River Mine will endure for millennia, and I mean multiple millennia,” says Mudd.

Despite decades of protest, led by elders including Green and McDinny, the NT government has always been determined for the mine at McArthur River to go ahead.

Back when digging began in 1995, it was supposed to be an underground mine with a 15-year lifespan that would see it close in 2010. But then in 2005 Xstrata made a dramatic proposal — the mine would become open-cut and remain in use until 2027. And it would divert a 5km stretch of the McArthur River, destroying the Rainbow Serpent Dreaming in the process.

The NT Environment Protection Authority (EPA) rejected the proposal, but the government invited the mine to have a second go at crafting and lodging a plan. This time, despite the EPA’s criticisms, both the NT and Commonwealth ministers signed off on the project.

Then traditional owners went to court, launching dual proceedings in the Territory’s Supreme Court and Federal Court. They eventually won both cases, but that didn’t stop the conversion from underground to open-cut.

Within days of the Supreme Court decision, the NT parliament voted to override it (although three Aboriginal government MPs took the rare step of crossing the floor, and the environment minister was absent from the chamber). And by the time of the Federal Court victory some 18 months later, the river had already been diverted. After inviting the mine to submit new documents for a fresh determination under the federal law, and a 10-day public consultation period, the federal government approved the project again two months after the court decision.

“When the open-cut mine [came], that’s when the problem started,” says Green. “There’s a lot of damage, dug up a lot of songlines and that on the McArthur River.”

In 2013, the NT approved another expansion, doubling the size of the open pit, expanding the waste rock dump, and pushing the mine’s lifespan out another 10 years to 2037.

But the fire on the hill changed things. And so, just two years after its most recent laborious approval process wrapped up, the EPA decided that Glencore would again have to submit an environmental impact statement for approval in order to continue mining. The company would need to outline in detail how it would deal with the waste rock dump, and its plans for closing the mine in a safe way.

The notices posted in Garawa One and Garawa Two camps on April 19, 2018 warned the 100 or so residents of the camps not to drink water from their taps, or use it to clean teeth or cook.

“I was the first one to find out,” Gadrian Hoosan recalls. “I was at the health clinic, and someone came up from the clinic with a piece of paper and told me that the water was contaminated at Garawa One camp. And they gave me a paper to go and warn everybody around the community, to let them know the water was contaminated with lead and manganese in it.”

Two sample sites had turned up elevated levels of lead during routine government testing, and one also had elevated levels of manganese, the NT health department said at the time. Consuming lead is particularly dangerous for kids, with impacts on childhood brain development and learning, and can lead to anaemia, and kidney and nerve damage. The notices advised that babies, young children and pregnant women were “most likely” to be affected, but said it was a “short-term problem”.

For weeks, until the warning was lifted in Garawa One in May 2018, and in Garawa Two the following month, residents were drinking from water trucked over from the main town, or from bottles they’d filled up elsewhere.

“We all got shock when we heard that termination water,” McDinny says. “Everybody. They was frightened to touch that water from the tap.”

Hoosan and other leaders called for the NT government to provide the community with mass blood testing. But it refused, saying that the water had historically measured within guidelines, and residents had only been exposed to the contaminated water for a short time.

The government insisted that the problem had arisen because of corroding piping and fittings in the water reticulation system. But with a huge lead mine about 70km down the river, Hoosan, Anderson and others developed a theory that they still hold onto, despite denials from the NT government and Glencore: that their bore was contaminated, and the mine was to blame.

Sitting outside her parents’ home at Garawa One, Darilyn Anderson points to the bore that serves both town camps. It sits close to the riverbank. She says that when the river floods, water surrounds the bore and could seep through the soil into the drinking water stored below. Anderson and Hoosan say the mine releases contaminants into the river in the wet season (it has a licence allowing it to undertake controlled discharges of waste water into the McArthur River). “We worried for stuff will come down [the river from the mine]. We don’t know what’s come down,” she says.

More than a year since the warning was lifted, Anderson, Hoosan and others still refuse to drink from their taps. Anderson makes sure her three children, aged 12, 11 and 9, avoid drinking water from the camp’s bore. A number of other residents say they do the same. “I get bottle from the shop, I go to outstation,” she explains.

“We still worried for our water,” Anderson says. “It tastes funny.”

In 2017, four years after the combustion started, Glencore finally revealed how it planned to tackle the problems caused by its misclassification of the reactive rock, in a draft environmental impact statement (EIS) filed with the EPA. The plan is to store the majority of waste rock in a redesigned waste rock dump, to securely store the reactive rock it didn’t account for. That will almost double the height of the dump, from 80 metres to 140 metres.

It also spells out a multi-stage plan for the mine’s closure. Glencore will push commercial operations out by an extra decade to 2047, digging until 2037 and then reprocessing tailings for 10 years. In 2032, the company will cap the waste rock dump with a special geosynthetic liner to prevent oxidisation — and leave that huge pile of reactive rock on the Earth’s surface forever.

In the final few years of digging, waste rock and reprocessed tailings will go back into the open pit. Over several wet seasons, the company will fill the open pit with water. Finally, by 2073, Glencore plans to open the levee walls it built in the open-cut transition, letting water flow over the toxic materials through the original path of the McArthur River. Then comes nearly a thousand years — until 3037 — of ongoing monitoring and maintenance, which the mine insists will eventually be intermittent, low intensity and low cost.

“They’re going to be leaving a huge toxic time bomb above ground with the waste dump,” says Mudd, who argues that leaving the dump above ground is unsustainable unless you actively manage the site in perpetuity. “I think it’s indefensible.”

Glencore’s plan rejected Mudd’s preferred way of dealing with the risk of toxic waste seeping from the waste rock dump into the water systems: a complete pit backfill. That plan, which was also supported by the NT Environmental Defenders Office clients, would mean that instead of leaving the waste rock on the riverbank, it would all go back into the open cut pit and be sealed.

It’s a rare and expensive avenue, but one that’s warranted by the unusual circumstances, Mudd argues. Glencore didn’t accept it, saying it would render the project “uneconomic and unviable”. A spokesperson for the company told BuzzFeed News they rejected the claim that the pit backfill was the most environmentally safe approach, and said the approach they had chosen was the best environmental outcome.

In July 2018, despite these criticisms, the EPA recommended the mine’s plan to manage the waste rock dump be accepted. But the thumbs-up was conditional on the mine adopting 30 recommendations, anchored by one overriding imperative — that the mine implement its proposal, and all future stages of the mine, “in a manner that requires the health of the river to be protected along its entire length at all times from mine related impacts”. Neither those recommendations, nor the EPA’s approval, are binding. The final call lies with the NT’s primary industry and resources minister, Paul Kirby.

Extraordinarily, the EPA gave its approval without making a call on how the mine should be closed. Ducking the question, it said that because the mine wouldn’t close for at least 20 years judgements on the merits of different closure options were “premature in the absence of comprehensive data on long term outcomes and the likelihood of improved technologies and more appropriate solutions to emerge over time”.

The EPA’s optimistic position aligns neatly with a bitter reality facing the NT government — to avert an environmental disaster, it now needs the mine to stay. The EPA admitted as much when discussing the “no project” option — the argument that the mine should be forced to wind down and leave, given the trouble that it’s caused. That option is “more likely to result in uncontrolled and unacceptable outcomes for the environment” than the proposal in the EIS, if the mine adopts the 30 recommendations and ensures the health of the McArthur River, the EPA said.

The EPA’s approach is “highly concerning and contrary to key environmental principles”, says Duggin. “Effectively the EPA has kicked the can down the road. That’s contrary to foundational principles, which say you shouldn’t permit something to go ahead when there’s so much uncertainty about what the impact could be.”

Duggin is critical of the NT government’s regulation of the mine, and says it is partly to blame for Glencore’s rock misclassification mistake persisting. “If environmental laws in the NT were working effectively, it shouldn’t be able to have transpired,” she says. “It’s clear the government is in a difficult situation. It doesn’t have the technical or financial capacity to rehabilitate such a badly contaminated site. And therefore it feels like it needs to keep the mine operational in order to achieve a better outcome.

“This is the most potentially devastating of circumstances, that have demonstrated just how much the environmental laws of the Territory have failed.”

In Borroloola, Asman Rory tells me about recent events that have frightened him. Driving on the highway, with his partner in the passenger seat, he passed the waste rock dump. “I was driving along and then I seen my missus,” he recalls. “I could just glance at her and I thought straight away something was wrong. She stopped talking for about five minutes. I just sped off out of that area and tried to get her in clean air. It was actually something burning from the dump.”

His girlfriend had passed out, and her voice was croaky for a few weeks afterwards, he says. A few days later, it happened again. Both times, he says she lost consciousness. Others say they can still smell the dump as they drive past it, and that it will make them cough or give them a sore throat.

More serious health problems are also blamed on the mine. “Why the hell we keep getting sick?” Jack Green demands to know. “There’s gotta be something causing that in Borroloola. We never used to have this dialysis thing before, kidney problems, heart attacks.” McDinny also complains about a growing number of young people going on dialysis, then dying. “We don’t know where they get it from, I think from the river,” she says.

The Glencore spokesperson said it had not been made aware of the incident Rory described, and that its air quality monitors had not detected significantly elevated levels of sulphur dioxide at any point in the last two years. “We have no evidence to suggest any link between our operations and health issues in the Borroloola community,” he said.

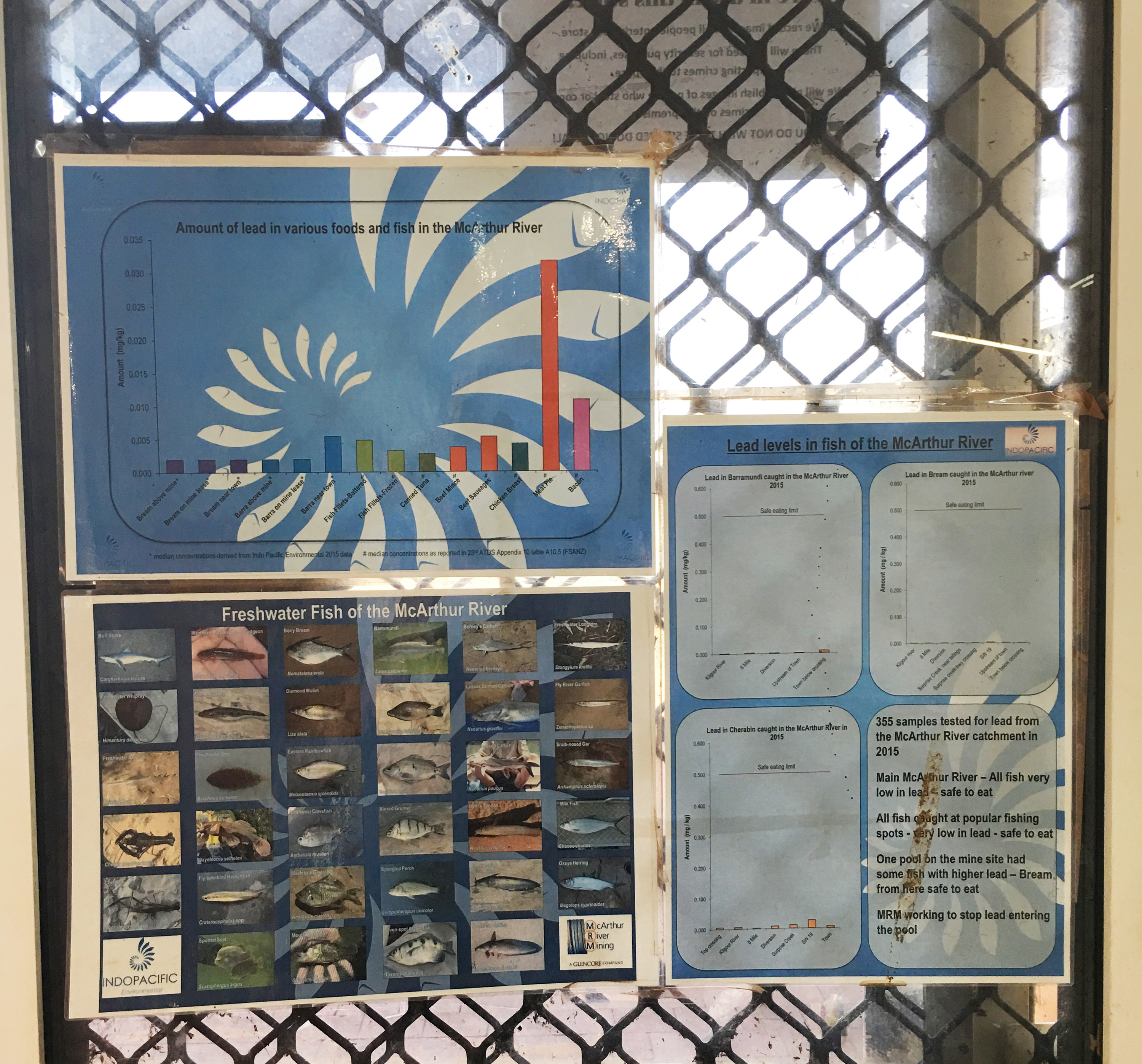

Fears over health and environmental damage have been acute since the waste rock dump began to burn in late 2013, with a series of incidents that the mine and government have not always been up-front about. For several consecutive years fish on the mine site were found to have excessive lead levels — including some fish that people eat. In one creek, 90% of fish had unsafe lead levels. In 2015, the ABC revealed that Glencore had ignored the recommendation of the NT’s chief health officer that signs be erected warning people not to eat fish from two creeks or Bing Bong Port, where the mine loads minerals to be exported, because of the risk of heavy metals in fish.

Also in 2015, the NT government announced that a year earlier hundreds of cattle had been destroyed, and others quarantined, over fears they had been contaminated with lead after wandering on to the mine site. In 2016, mine workers told the ABC they were suffering serious respiratory problems after breathing in the toxic smoke from the burning rock. (A Glencore spokesperson told BuzzFeed News they were only aware of one workers compensation claim made by a former employee, which was declined by the insurer because the individual had a pre-existing medical condition and the level of exposure was well below the limit that could cause harm, and that the company had strong systems onsite to ensure safety.)

This recent history means people like Green and McDinny are suspicious that the mine is causing harm it’s not telling anyone about. A Glencore spokesperson said that the mine had made “considerable improvements” to its system preventing sediment contaminating water since lead was first detected in fish in 2012, and that studies showed its efforts had a “dramatic and positive effect”.

Recent reports from the mine’s independent monitor — an oversight body created when the mine transitioned to open-cut — say the mine is improving its performance on water and fish contamination, and that tested fish had metal levels below the maximum safety level.

But Green says he doesn’t trust the tests. He is not alone. “We need someone to work with Aboriginal people and test the water from the mining lease, working with some people connected to that land,” Green says. “If the water is good, the Senior Elders will support the company. If the water is no good, they will tell the company that water is no.”

Over in Garawa One, the evidence suggests the government was correct in blaming last year’s lead contamination on corroding water fittings. Tests of the groundwater never showed high lead results, and experts say the location of the testing sites and historical results support the theory that it was corroded piping, and not a contaminated bore. In mid-2018, the NT government says it replaced some pipework and fittings and made changes to the chlorine disinfection system to address the corrosiveness of the groundwater.

But that kind of evidence hasn’t put Anderson and Hoosan at ease. “I didn’t see any workers come up, digging up rusty pipes,” Anderson says.

The blood tests they called for might be the reassurance they need, however the residents and the government have reached an impasse. The NT health department insists mass screening is unnecessary because the exposure to lead only lasted a short time, and routine tests in previous years didn’t reveal elevated lead levels in drinking water. (The NT utility provider’s annual drinking water quality reports show a lead level equal to the safety limit in the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines was recorded at a sample site at Garawa with corroded brass fittings, and the same result was recorded the year before.)

The health department says that blood testing is available for individual cases if clinically warranted, for example if a child presented with behavioural problems or anaemia. But it also says there have not been any health issues relating to lead poisoning reported in Borroloola.

Hoosan, Green and McDinny are adamant the government should test everyone. Asked why they didn’t go to the local health clinic and ask for a test, residents had a variety of responses. A few said they had heard the clinic charged high fees for tests (the health department says they are free). Anderson says she heard somebody asked the clinic for a blood test but was told “they don’t do it here”.

Numerous Borroloola residents mention their lack of faith in the health clinic, which is not community-controlled, and which residents say has high staff turnover. A number said they felt as if doctors did not take their complaints seriously, and would often send them home with Panadol. In response, the health department said that “all clients attending the [clinic] are clinically assessed and treated according to the Central Australian Rural Practitioners Association standard treatment manual”.

Green, who has grandkids living at Garawa One, also blames cultural reasons for the reluctance to initiate a blood test on their own. “Aboriginal people — sometimes they don’t even go there and ask, they feel a bit shy,” he says.

Since the shock of the warnings about their drinking water, Borroloola locals say they haven’t heard much from the government. Although NT Health says its staff door-knocked to say the water was safe, Hoosan says he doesn’t think anyone came to let the community know. The NT government’s May budget included a $4.7 million allocation for a 6km water main connecting the Garawa communities to the Borroloola township’s water supply over the river, which since October 2018 has had a $6 million water treatment plant. But in the days after that announcement, the news had not filtered through to the community.

Mistrust in the mine and the government is widespread, and some people are scared.

“I think there’s a lot of cover-ups in Borroloola, a lot of cover-ups in that little town,” says Hoosan.

In June a delegate of federal environment minister Sussan Ley approved Glencore’s project. The date the approval expires? Jan. 30, 3019.

A spokesperson for Ley said the department agreed with the EPA that the impacts of the mine’s plan to deal with the waste rock on threatened species would be acceptable, “subject to strict conditions”. Most significantly, the approval conditions knock back Glencore’s proposal to reconnect the pit lake to the McArthur River, “as there is not sufficient understanding of the potential risks”. Another condition is that Glencore not cause any harm to the health of the McArthur River.

NT resources minister Paul Kirby didn’t directly answer questions about when he would make a final decision on the approval and whether he would fully implement all of the EPA’s recommendations. Instead, his spokesperson said that he was waiting for advice from departmental staff, who are in ongoing discussions with the mine.

“The minister will carefully consider the advice once it’s received to ensure subsequent decisions maintain our healthy environment and foster ongoing local jobs,” Kirby’s spokesperson said in an emailed statement. “Labor understands that a healthy environment is essential for long term local jobs.”

Duggin is critical of the fact the resources minister is responsible for approving mining plans and making decisions about environmental impact. In the NT, the environment minister can only refer the EPA’s recommendations on, but doesn’t have decision-making power. The final mining management plan is also ultimately confidential — and its details only come to light if the resources minister departs from the EPA’s recommendations and has to table that decision in parliament.

“One of the key problems here in the Territory is that the relationship between the mining industry and the department is just too close,” Duggin says. “There’s a real lack of recognition of the importance of environmental regulation and for appropriately resourcing it.”

Despite the EPA and federal government’s actions bringing Glencore ever closer to wrapping up this approvals process, there are murmurs around Borroloola that another court battle to put a halt to the mine’s plans could be on the horizon.

In a jurisdiction with an environmental assessment law that is only six pages, Aboriginal people who object to the mine don’t have a lot of options to have their say. But there is one avenue. In practice, to go ahead with its plans, Glencore needs approval from a small, independent statutory body that oversees the protection of Indigenous sacred sites — the Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority (AAPA).

Here’s why: the expansion of the waste rock dump to handle the misclassified reactive rock would obscure the view of the Barramundi Dreaming — a rocky ridge that is a sacred site for the Gudanji people — from the road. An authority certificate from the AAPA currently limits the dump to a height of 80 metres; the proposal would allow it to climb to 140 metres, and so the AAPA will need to issue another authority certificate for the plan to go ahead.

“The waste dump is growing higher and higher,” Jack Green says. “We feel no good because straight across from there, there’s a sacred site that we want to keep an eye on — the Barramundi Dreaming.”

The mine says it has consulted with the site's traditional owners and signed an agreement with them, showing their consent. But others aren’t so sure. Green says Glencore made an agreement with six people. He claims some of them aren't genuine local traditional owners, and that while some are, they don't represent all traditional owners. “Under Aboriginal law you can’t make decision if something is not your country,” he explains.

Green’s wife, Josie Davey, is a Gudanji woman who says her father is one of the signatories to the agreement, but complains that he hasn’t consulted with his family about what he’s doing. “I’m fighting for that place, whitefella way, through court,” Davey adds.

Green otherwise wouldn’t name the six, and nor would other members of the Borroloola community I spoke to about the agreement

The NT Environmental Defenders Office, on behalf of its clients, and the Northern Land Council have also questioned the legitimacy of the agreement about the height of the waste rock dump. The Northern Land Council’s submission to the environmental approval process described the agreement as “highly problematic” and said that it appeared that custodians of the sacred site had not been consulted, describing the consultation process as “grossly inadequate”. The submission on behalf of the Environmental Defenders Office clients suggested it might be regarded as “unconscionable”.

One of the EPA’s recommendations was that the mine should have to demonstrate that it undertook a “thorough process to identify, inform and consult with the appropriate custodians and traditional owners with an interest in lands that would be or may be affected by the proposal”. The question is now with the AAPA.

The AAPA’s processes are confidential, so it won’t say what it’s found or what it will do. But if Kirby agrees with all of the EPA recommendations, the authority certificate will be critical. So will the AAPA’s agreement that Glencore has undertaken appropriate consultation with custodians and traditional owners with an interest in all lands that may be affected — because the EPA has recommended that its sign-off be required for any approvals or decisions about the proposal.

Bruce King is a Garawa man and community leader, and a former mine employee. “I was working at the mine, but I couldn’t stand it — looking at our country getting damaged,” he says.

King says he was earning good money as a dump truck driver at the mine at the end of last year. He describes it as the easiest job he’s ever had. But he quit after a few months: he couldn’t bear to see the waste dump growing bigger.

“It didn’t work out,” he says. “Seeing all that damage that’d be done and gonna continue, it’s just not on,” he says.

In its proposal to keep mining for the next 20 years, despite misclassifying the reactive rock, Glencore points out a number of times the socio-economic benefits it brings to the local area: jobs, money for the community, infrastructure. NT resources minister Paul Kirby also emphasises the importance of jobs.

But what has the mine actually given the people of Borroloola? It says it currently employs 32 people from the local region, but a recent review of the NT’s town camps by accounting giant Deloitte found that Glencore had a limited Aboriginal employment program. “Engagement of local people in mine services is sporadic,” the report says.

The mine also cites its Community Benefits Trust, a fund it runs with the NT government for Borroloola that has put $17 million into the town over 12 years. It’s bankrolled projects for the local school, as well as providing community members with spare seats on the flights that go between Darwin and the mine — which otherwise cost $700 for a one-hour trip — for people to get medical treatment, attend conferences, or meet cultural responsibilities. But Hoosan argues that the mine is selective about who it gives funding to. “It’s only helping the certain people that they favour, that’s it,” he says.

Glencore has also paid for a swimming pool, a renal dialysis unit and X-ray equipment for the clinic. “Borroloola was entitled to that anyway,” Asman Rory says, saying the government should have funded those facilities.

“We also believe the best thing we can do for the local community is to run a safe, responsible and sustainable operation that provides local employment opportunities and procures goods and services from local, often small- and medium-sized businesses,” Glencore’s spokesperson said.

And what has the mine given the cash-strapped Northern Territory? Glencore has published annual reports showing payments to governments throughout the world each year since 2015, and they reveal it has not paid any royalties to the NT government from the McArthur River project in that time – unlike other jurisdictions, royalties in the NT are calculated based on profit, not revenue.

Regardless of the community trust fund and its projects, Borroloola and its town camps are beset with economic and social problems. “If you got a million dollar mine just 70km down the road, we shouldn’t have problems with housing, we shouldn’t have problems with roads, we shouldn’t have problems with water,” says one woman.

Nancy McDinny doesn’t want the mine’s money. “We’d be nothing without the river,” she tells me. “If it gets damaged and stories for us out in the bush, we’d be gone for good. None of us will know it again. That will just be ripping the songlines off too, on the land.

“Say if you have a story book in front of you, and you rip that book off, you got no story. But what you can do, you can replace that book. But if you rip the story off our land, you can’t replace it. It’s gone for good. And no money can bring that back. No money will ever bring it back,” she says.

“There’s a fair few family saying [the mine] is a good thing,” Bruce King says. “It’s not. Even the royalty they’re providing the community with, it didn’t really change anything. It wasn’t worth it. The river’s slowly dying. The food is not trusted anymore to eat from the river. I been travelling up that river since I was a little boy. It’s totally damaged now. There’s no life, nothing, where it used to be full of life.”

“I think this world is changing,” King laments. “Money is taking over the bush life — our life.”

On my last day in Borroloola, I ask Green to drive with me to the mine and show me the Barramundi Dreaming. As we motor along the highway, he points out other sacred sites, the frog and the snake line.

Sitting in the passenger seat, Green sounds tired. He tells me how Aboriginal people from the four clan groups used to come together and discuss issues before deciding a position. It doesn’t happen anymore. “All the old people passed away,” he says.

That morning, I’d visited the Borroloola Museum, a small converted 19th century police station with no staff. In a section focusing on changing relations between Aboriginal people and white settlers in the area, there’s a picture from 1928 that shows four Aboriginal prisoners in police detention. The accompanying text explained that there were no lock-up facilities back then, and a single police officer might transport Aboriginal people they arrested in the bush hundreds of kilometres without vehicles. The men were chained together by metal collars around their necks.

Jack Green talks about this history as we drive. “To me that chain has never been released properly,” he says. “We’re tied up with rope now, not chains. That’s how I feel inside.”

Still, Green keeps fighting. “If you look at Borroloola properly, we can get our control back if we work together as Aboriginal people,” he says.

“We just little people, me and you,” one woman, who asked for her name to be withheld because of her employment, tells me. “This country is run by the government and rich people. Rich people, they give their money to the government, they make deal. Rich people are the miners and they can do whatever they want.”

When I ask whether they sometimes feel powerless, Nancy McDinny and Gadrian Hoosan give a vigorous response. “We don’t,” says Hoosan. “They make us stronger, get up and stand up and fight more. We don’t have a choice, but we have to stand up and speak for it.”

McDinny adds: “Because that land and river won’t speak for themselves.”