At first, Thomas* thought there was a misunderstanding.

The letter from Australia’s Department of Immigration and Border Protection in Aug. 2017 said it was considering cancelling his visa — which would mean deportation to New Zealand.

But Thomas, now 35, was Aboriginal. He had learnt about his Aboriginal heritage at a family reunion in 2012, tracing his family tree back to the Palawa people of Tasmania. His ancestors were taken from the Tasmanian mainland to the settlement of Wybalenna on Flinders Island, he discovered. His nan’s great grandfather escaped by sailing to New Zealand.

His family lived in New Zealand until 2005, when Thomas, who also has Maori heritage, moved to Western Australia with the woman who he would later marry, Anna, who is now 34*. (*Names changed to protect privacy.)

Thomas was proud of his Aboriginal heritage, calling it a “blessing”.

“I come from this land, my bloodline comes from this land,” he told BuzzFeed News. “It’s part of me.”

A string of offences from 2006-2015, mainly related to domestic violence and driving, led to his imprisonment from Oct. 2015 to Feb. 2016. In turn, that triggered the ‘‘character’’ provisions of Australia’s Migration Act, and the department’s letter saying they were considering cancelling his permanent visa.

“I thought they were barking up the wrong tree,” said Anna, who reconciled with Thomas in June 2016, after a few years of separation. “I thought if they were notified of the fact that he was Aboriginal that would completely change things.”

Thomas and Anna did not know it at the time, but he had found himself in the middle of a complex issue that would eventually reach the High Court — whether the government can constitutionally deport Aboriginal people with a significant connection to Australia.

Daniel Love, who was born in Papua New Guinea to an Aboriginal Australian father and has lived in Australia since he was six, spent two months in detention last year.

Brendan Thoms, a New Zealand citizen with an Aboriginal mother who has lived in Australia since he was five, has been in detention for over six months.

In cases to be heard together in May, both are suing the Australian government: Love is seeking damages for false imprisonment and Thoms his release. They say Aboriginal Australians cannot be considered “aliens” under the constitution.

Replying to the department’s notification in Sept. 2017, Thomas said he was Aboriginal Australian by descent, which had been previously recognised by other government departments. Two weeks later, after a family meeting, he sent more information about his heritage, including his family tree.

The department responded by asking for more information about his parents, and then in November informed him by letter that he was not an Australian citizen.

That letter made him feel “terrible”, Thomas said. “Telling us who we are and who we’re not — how dare someone say it doesn’t really matter if your family comes from here, we don’t care?”

Thomas replied to the department in January suggesting the reason it might not be able to find evidence of his citizenship was because of the “governmental genocide carried out on the First Australian Palawa people in the 1830s – my ancestors!”

“Let me firstly and most importantly speak to your confidence in telling me I am not a citizen,” he wrote. “I match your confidence in knowing who I am. I am a direct descendant of the Palawa people. This is my country.”

Thomas’ reaction to his Australian identity being questioned is “common”, director of Macquarie University’s Social Justice Clinic and special counsel to the National Justice Project Daniel Ghezelbash told BuzzFeed News. Ghezelbash has been involved in several cases of other Aboriginal men with cancelled visas.

“It’s a dissonance between what an average individual, particularly an Aboriginal Australian, would understand as being Australian, and what is prescribed by the law,” Ghezelbash said.

“There are very clear criteria under the Citizenship Act about who is and who isn’t an Australian citizen, and Aboriginality is just not a factor.”

In his response, Thomas argued that he identified as Aboriginal, was accepted as Aboriginal, and was descended from Aboriginal people.

“I ... deny your insinuation that an aboriginal is not a citizen of this land now called Australia,” Thomas wrote. “There is deep pain caused by denying someone of their rightful home. I would hope that displacement of the original inhabitants of this land was of importance to any government department in existence today.”

He included references from a number of people who confirmed he identified as Aboriginal — including Anna, who said that she had applied for Australian citizenship four years ago, because of her own two sons’ Aboriginality.

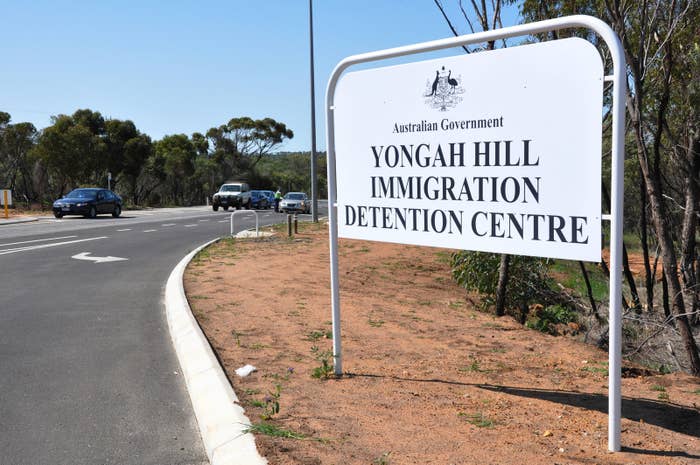

It would be nearly a year before Thomas heard from the department again. Although the department had decided to cancel his visa in June 2018, it wasn’t until Oct. 26, 2018 that a group of about eight officers came to Anna’s door looking for Thomas. They searched the house, but he had just left for work. He handed himself in to be taken into immigration detention at Yongah Hill a few days later.

While the document outlining the reasons for the visa cancellation ran to nine pages, Thomas’ Aboriginal heritage was dealt with in two short paragraphs near the end.

The decision-maker, a delegate of home affairs minister Peter Dutton, “noted” Thomas’ “submission that he is an Australian citizen as he is a direct descendant of the Palawa people”, but said he was not a citizen.

“I do not question his Aboriginal descent,” it went on. “I accept that removal from Australia will cause [him] emotional hardship. However I also note that [he] lists his mother as being of Maori and Aboriginal descent and his father as being of Maori descent. I find [he] has strong indigenous ties to his country of citizenship, New Zealand”. Thomas would not experience substantial language or cultural barriers in NZ, and he would have access to health, welfare and support services there, they concluded.

One reason Thomas’ protestations that he was Aboriginal were largely ignored is that, as with the Citizenship Act and the Migration Act, the ministerial direction that tells departmental officers what to consider when deciding on visa cancellations does not mention Indigenous Australians.

An “express provision that this should be taken into account” would “go a long way” to fixing the problem, Ghezelbash said.

Thomas spent three months in detention before he successfully appealed to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal and was released in late January.

Unlike the government, the tribunal looked at his Aboriginal background in detail and largely relied on it in deciding that he should keep his visa. Although he was of bad character, the tribunal found, his deportation would have a detrimental impact on his children’s cultural identity, and his Aboriginal background contributed to his “very strong” ties to the Australian community.

Even though Thomas was never deported, Anna told BuzzFeed News her 8- and 12-year-old sons were “so confused” by the process, which has shaken their sense of belonging.

Thomas and Anna’s third child is due in May, and they are hoping to visit Tasmania as a family this year.

“It’s historical, if you like, but I find even that part compelling,” Anna said of Thomas’ lineage. “The fact that he was only denied his Aboriginal heritage because his great-grandfather travelled to New Zealand as a result of the Australian government – it’s almost a repeat of that history, in my view.”

Do you know more? Contact this reporter at hannah.ryan@buzzfeed.com or on Signal at +61 488 601 373