Queensland surgeon Dr David Grundmann went to work on the morning of May 20, 1985, at the Townsville clinic at which he was the medical director. By midday he was holed up in a police station.

"It came completely out of the blue when the police came into the premises and requested that everything be stopped, produced a search warrant and charged me with performing illegal abortions," Grundmann, 70, told BuzzFeed News.

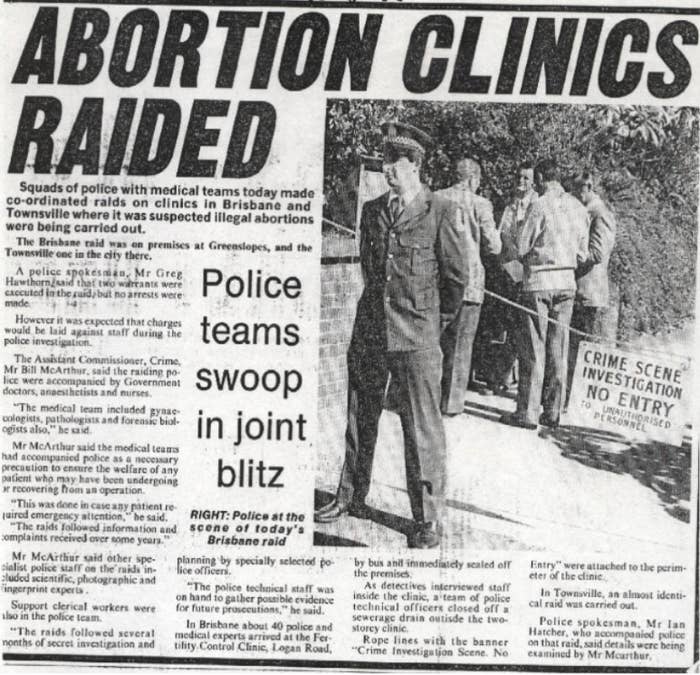

At 10am on that morning more than 100 police officers entered two Queensland clinics - one in Townsville and the other in Brisbane - where they seized equipment and confiscated around 47,000 patient files in what Grundmann described as a "military-like raid".

Grundmann and surgeon Dr Peter Bayliss of Brisbane's Greenslopes clinic were charged with conspiracy to perform illegal abortions.

The raids, and ensuing legal battle, would shift the parameters within which abortion could be lawful in Queensland by setting a legal precedent.

On that same morning in 1985, at Brisbane pregnancy counselling service Children by Choice, counsellor Lorraine Smit said the phone started to "ring off the hook".

"I took the first phone call and it was this woman who had been in to see us a couple of days before," Smit, 71, told BuzzFeed News. "She said, 'My appointment is at [Brisbane's Greenslopes Clinic] this morning and the streets are all cordoned off and there are police everywhere. What am I going to do?' So I told her to come back here.

"It was something we knew could happen at any time, but we didn't think it ever really would."

Children by Choice, which at that time was mostly run by volunteers, had a policy of periodically removing client names from their (paper) files for confidentiality reasons.

"So I was there all day with the scissors frantically cutting out every name on the files in case the police came," Smit recalled.

The raids came as a surprise, she said, as the police had always been "on side" with the clinics, and even came by to check on counsellors when there were protesters outside the Children by Choice building.

Grundmann said his "main concern" on the day was the fate of dozens of women who were travelling from regional and rural Queensland to terminate their pregnancies at "considerable cost and inconvenience".

"I was worried my operation would be stopped for a considerable period of time and there would be a lot of women who came to see me who would be seriously disadvantaged... as they would [now] have to go to NSW.

"Right up until 2005 we had patients who were refused contraception by their local pharmacists, who were deliberately misdiagnosed as being too late to have an abortion by a GP."

Until Grundmann opened a second clinic in Rockhampton, patients were travelling from as far away as Bundaberg (1007km), Weipa (1140km) and Mt Isa (904km).

Grundmann escaped prosecution.

"My case was thrown out on a [technicality]... and I resumed work the next day. But Peter wasn't so lucky."

Bayliss and his lawyers filed a complaint to the Supreme Court of Queensland seeking the return of all patient files.

Three judges unanimously ruled that search warrants used to raid the clinics were invalid and files were returned to the clinics, which Bayliss said at the time was a huge relief to his patients, who had wondered “who had been poring over their private and confidential medical files”.

The legal battle wasn't over for Bayliss.

Director of Public Prosecutions Des Sturgess tried to restrict Bayliss’ bail conditions to stop him from performing abortions.

Sturgess then made a public plea for patients of the Greenslopes clinic who were "dissatisfied with their abortion" to come forward with complaints about Bayliss.

Eventually, one woman volunteered.

The mother of three had booked into Greenslopes for a termination in 1984 for an unwanted pregnancy. She said she could not afford another child, and requested sterilisation.

During the abortion the woman suffered heavy bleeding and was transferred to the Royal Women’s Hospital where she had a hysterectomy to stop the hemorrhaging. She later recovered.

The woman went on to give evidence that she thought she would receive a financial award for making the complaint.

The woman told the court that she had told a counsellor at Greenslopes clinic that she could not cope physically, mentally or financially with another child.

Anaesthetist Dawn Cullen, who had assisted with the woman's abortion, was charged and prosecuted alongside Bayliss.

Lawyers, doctors, anti-abortion protesters and members of women’s organisations overflowed from the public gallery of Brisbane’s District Court for the trial, during which Burgess attempted to convince a jury that Bayliss and Cullen – who had pleaded not guilty – had performed an unlawful abortion.

That is, that the doctors did not have an “honest belief, on reasonable grounds, that the abortion was necessary to preserve the patient from serious danger to her mental or physical health”.

Sturgess, who claimed Greenslopes was “an abortion factory”, did not convince the jury the procedure was unlawful and the pair walked free.

Justice Fred McGuire found that “in exceptional cases”, an abortion would not be unlawful where it was carried out in good faith to avoid “serious danger to the mother’s life or her physical or mental health (not merely the normal dangers of pregnancy and childbirth) which the continuation of the pregnancy would entail”.

Grundmann believes the 1985 raids were a planned but miscalculated political move.

"It clearly didn't come out of the blue to the media because they were there ready with video cameras," he said.

The case set a precedent, but McGuire noted that it illustrated the "uncertainty" of abortion law in Queensland.

For the past three decades women and doctors have had this case law to "protect" them against charges.

No doctor has been prosecuted over unlawful abortion since the case, but a woman and her boyfriend have.

In 2009 Cairns woman Tegan Leach was charged with procuring her own termination with medical abortion drugs.

When Leach, then 19, faced an unplanned pregnancy, she knew she didn't want to have a surgical abortion but was "pretty sure" drugs to procure a medical abortion were not available in Australia, she later told police.

Leach's boyfriend Sergie Brennan, who was charged with assisting her, spoke to his sister in Ukraine, who sent two types of abortion drugs to Cairns with which Leach miscarried.

Police found the pharmaceutical evidence of the medical abortion when searching the couple's home in relation to another matter, and they were charged with intentionally procuring a miscarriage.

Both faced jail if found guilty.

They were forced to move to a secret location after a Molotov cocktail was allegedly thrown at their Cairns home.

Eighteen months later a jury took less than an hour to find the couple not guilty.

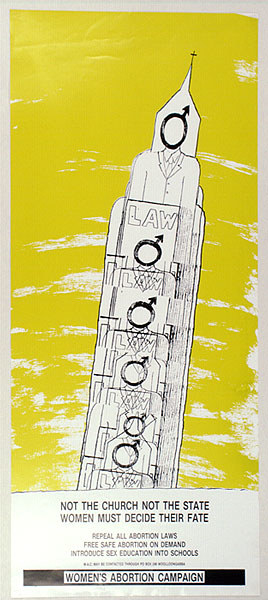

Two bills to decriminalise abortion in Queensland were withdrawn last week by independent Cairns MP Rob Pyne when it became clear they would not pass parliament.

But the legislation has been referred to the Queensland Law Reform Commission for review, and the Labor government has promised to introduce a bill to "modernise" the state's abortion laws, if reelected.