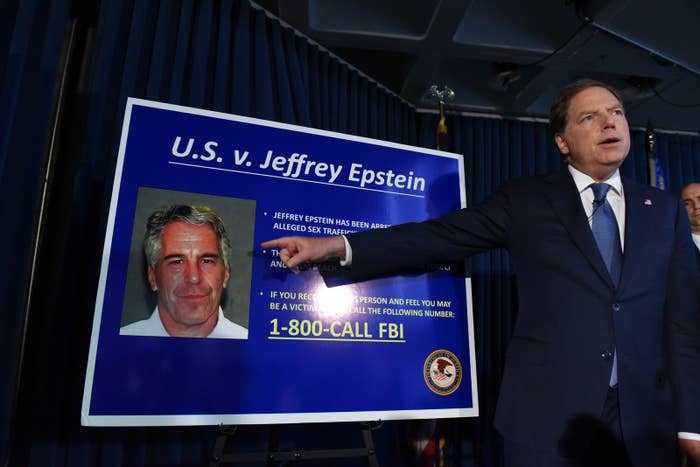

Jeffrey Epstein’s Upper East Side mansion has become notorious for its reportedly macabre interior decor, immense size and monetary value, and as the site of some of his lurid alleged crimes.

But Epstein, the financier who has been charged with sex trafficking and accused of sexually abusing young girls, used to live in a different Upper East Side mansion only a few blocks away. It's a mansion that embroiled him in a dispute involving a lawyer for French Connection heroin ring suspects, the State Department, and transitively the government of Iran.

The now-forgotten case — laid out in newspaper clips from the time and extensive court documents — offers a glimpse into a strange facet of Epstein’s life at the time, and constitutes an early example of Epstein popping up in the media as a rich and connected but mysterious New York figure.

Beginning in February 1992, Epstein rented a former Iranian government building that had been taken over by the State Department during the Iranian revolution, at 34 East 69th Street in one of Manhattan’s most expensive neighborhoods, and at a rate of $15,000 a month.

But things went sour when the government sued Epstein in the Southern District of New York, alleging that he had at one point failed to pay the rent on time and had violated the lease by moving out in early 1996 and subletting the place without the State Department’s permission. His subtenant was Ivan Fisher, a New York City criminal defense lawyer who had famously defended members of the French Connection and Pizza Connection drug rings. The government also sued Fisher.

A lawyer for Epstein did not respond to a request for comment, and attempts to reach Fisher were unsuccessful.

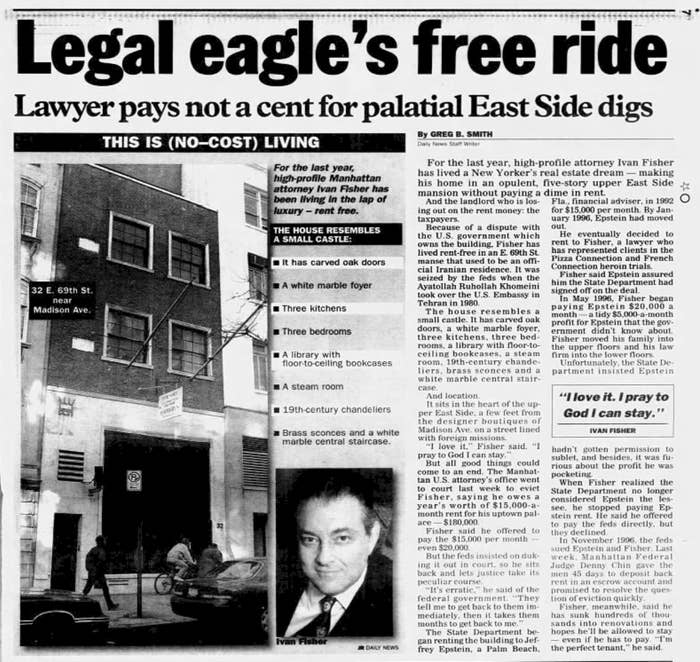

A New York Daily News article from the time, headlined “Lawyer Pays Not A Cent For Palatial East Side Digs,” said Fisher had stopped paying rent after learning that the State Department had terminated Epstein’s lease as a result of the conflict over Fisher’s subtenancy, and was thus living in the home for free.

“I’m the perfect tenant,” Fisher told the Daily News. The paper described the home’s opulence: “carved oak doors, a white marble foyer, three kitchens, three bedrooms, a library with floor-to-ceiling bookcases, a steam room, 19th-century chandeliers, brass sconces, and a white marble central staircase.” “I pray to God I can stay,” Fisher told the Daily News.

Epstein is described in the story as a “Palm Beach, Fla., financial advisor.” The incident is also briefly mentioned in Vicky Ward’s 2003 Vanity Fair profile of Epstein.

The government’s complaint rested on its assertion that Epstein had not received permission before installing Fisher as the subtenant, and its grievance with Epstein was only intensified by his charging Fisher $20,000 a month for the rent when State was charging $15,000 — netting Epstein a monthly profit.

The voluminous court documents in the case include a later-amended complaint by the government, which added more defendants to the suit — a clutch of other lawyers whom, the government alleged, were in turn subletting office space from Fisher. In a sworn statement, one of those lawyers, Lawrence Gerzog, told the court that he had given Fisher free legal services in exchange for office space, among several other lawyers.

The government eventually moved to evict Fisher, and the court ordered Fisher and Epstein — who in the course of the process were eventually involved in litigation against each other — to pay the back rent and to vacate the premises. An eviction order was served on July 16, 1998, and the marshal noted on the service receipt that the tenants had moved out.

Getting there wasn’t an easy process for the State Department, which had begun by exchanging strongly worded letters with Epstein’s lawyer, Jeffrey Schantz. These were included in the court filings.

“As you are aware, Mr. Epstein’s apparent departure from the house and his failure to make timely rental payments in February and March of this year have been matters of serious concern to this office,” wrote Thomas E. Burns Jr., then the deputy director of the Office of Foreign Missions, in April 1996 in a letter attached to court filings. Burns wrote that the OFM had already found someone to take over the lease from Epstein, a developer named Xenophon Galinas, and that they would not approve the sublease to Fisher.

In June, Burns wrote again, this time directly to Epstein, to notify him that he had violated the lease by leaving the property and subletting it and give him 30 days to kick Fisher out and move in again himself. In August, Burns wrote again to tell Epstein that because Fisher was still there, the State Department was ending the lease. At the end of October, the government filed suit.

Epstein was accused of carrying out an effort to put someone else in the house in his stead without clearing it with the State Department. When Richard C. Massey, an OFM official who had been the point person for Epstein’s lease, was deposed in 1997 by the defendants’ lawyers, he told them Epstein had appeared to make a concerted effort to put someone else in the property without State knowing. “Mr. Epstein was shopping the property around town without our knowledge, all over town,” Massey said. “We had calls from real estate agents who asked us about it. I do not know how many people in the City of New York had a copy of Mr. Epstein’s lease.”

Massey was not able to be reached for comment.

What was Epstein up to? Why had he abandoned the decadent mansion so abruptly and moved out without getting permission to sublet? Epstein made it publicly known when he was moving out, telling the New York Times in January 1996 that the mansion on East 71st Street that would become famous in the context of his alleged crimes was now his. It belonged to Epstein’s client and mentor Les Wexner. It’s unclear how much Epstein paid for the house, if anything, as it was reportedly transferred without a purchase price from a trust linked to both him and Wexner to a company controlled by Epstein.

Fisher, who reportedly once counseled law students to look into a mirror and practice telling potential clients their retainer was $100,000, was banned from practicing in federal court in the Southern District of New York in 2013 after a court grievance committee ruled that he had stolen money from a client.