A committee of Florida’s House voted on Tuesday to recommend moving forward with a controversial bill reforming defamation law that First Amendment advocates decried to the legislators as representing “a death knell for American traditions of free speech.”

At a hearing at the Capitol in Tallahassee, the Civil Justice Subcommittee voted in favor of moving ahead with HB 991 despite fears that it could chill press freedoms and public debate. All 13 Republicans and one Democrat on the committee voted to advance the bill, while the four other Democrat members voted against it.

The bill’s author, Republican state Rep. Alex Andrade, told the committee that it would not change the legal elements of defamation, which require that a person falsely assert a fact — and not a mere opinion — that then causes harm to another person’s reputation.

“As one of my favorite people to listen to, Ben Shapiro, always says, ‘Facts don't care about your feelings,’” Andrade told the committee. “You're entitled to your statements of opinion. You're entitled to your personal subjective viewpoints. This bill doesn't change that.”

But a dozen members of the public — including defense attorneys, free press advocates, and LGBTQ activists — all rose to speak against the bill, warning that it likely contravenes long-standing Supreme Court precedent designed to shield news media if they make mistakes while reporting on public officials in the name of protecting a vigorous public discourse.

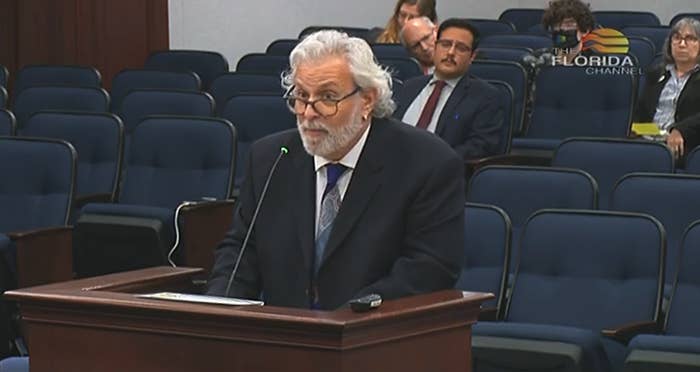

“We think the overall bill is really an attack on all speech — not just media, but citizens as well,” Samuel Morley, general counsel for the Florida Press Association, told the committee.

“The bill violates the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, it likely violates Florida's constitution, and it sets troubling public policy,” said Carol LoCicero, a Tampa-based attorney who has defended clients in defamation cases. “The First Amendment issues are severe.”

“HB 991 weaponizes defamation law to the point that it represents a death knell for American traditions of free speech,” said Bobby Block, executive director of the Florida First Amendment Foundation. “If HB 991 becomes law, its provisions will be used to try to crush critics of government policy.”

At issue are several major changes the bill will make to defamation law in Florida that could lead to a rush of lawsuits against media and nonmedia figures.

Current Supreme Court precedent stemming from the 1964 case of New York Times v. Sullivan requires that a plaintiff who is a public figure must prove a defendant acted with “actual malice” in making their false claim, meaning they must show the person acted either with knowledge of or reckless disregard for its falsity.

While Andrade insisted his bill did not change this standard, his bill would, among other things, narrow the definition of who is and is not a public figure.

It would also allow fact-finders to infer that actual malice has been demonstrated when there are “obvious reasons to doubt” the claim, whether because “there is sufficient evidence to the contrary” or it is “inherently improbable or implausible on its face.”

Additionally, public figures would also not need to prove actual malice by the defendant if the claim doesn’t relate to the reason for their public status.

Further, HB 991 would establish a presumption that any statement by an anonymous source in a story is false for defamation purposes. If a reporter refuses to identify their anonymous source, the plaintiff — even if they are an elected public official — is only required to show they acted negligently, which is a much lower legal standard than actual malice.

Despite most experts saying otherwise, Andrade has defended his bill as being constitutional. Still, at least one Republican on the committee said he hoped that it would eventually land before the Supreme Court as an opportunity to revisit Sullivan.

“Maybe this bill will be the occasion for New York Times v. Sullivan to be revisited or overruled or narrowed,” said state Rep. Mike Beltran, a Republican, shortly before voting in favor of the bill.

Several members of the committee, including Republicans, did say they had concerns about sections of the bill that would alter requirements about which party must pay for the other’s attorney fees, fearing it might undermine laws aimed at preventing retaliatory or frivolous lawsuits designed to silence critics.

Some said they hoped amendments would be made to the bill, which has also been referred to the House’s Judiciary Committee for review, before it is brought up for further consideration by the full House.

John Harris Maurer, public policy director for the LGBTQ group Equality Florida, told the committee that the bill also needs further clarification in a section that deals with defamatory allegations of discrimination against queer people.

Currently, the bill states that a defendant cannot try to prove the truth of their claim by citing the plaintiff’s scientific or “constitutionally protected religious expression or beliefs.”

Andrade insisted that his bill means that a defendant cannot use such statements as their sole piece of evidence, but Harris Maurer said this was not clear in the text.

“This bill is sexist, racist, homophobic, and transphobic,” Harris Maurer said. “Why? Because it restricts people's ability to call out sexism, racism, homophobia, and transphobia. It is politically motivated.”

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who is widely reported to be preparing to announce a run for president, has been vocal about his plans to roll back press freedoms. DeSantis also hosted a roundtable on defamation last month with right-wing figures that foreshadowed the legislation.

After the meeting, Block with the First Amendment Foundation told BuzzFeed News he was disappointed that the bill had made it over its first hurdle, but that he suspected state Republicans would soon feel pressure to vote against it from conservative media, who would be just as at risk from defamation claims as other press.

“A law like this is kind of like weaponizing a virus or bacteria,” Block said. “Once you release it into the wild, you have no idea what it’s going to do. You can’t control any of it. It could swing around and bite you in the ass.”