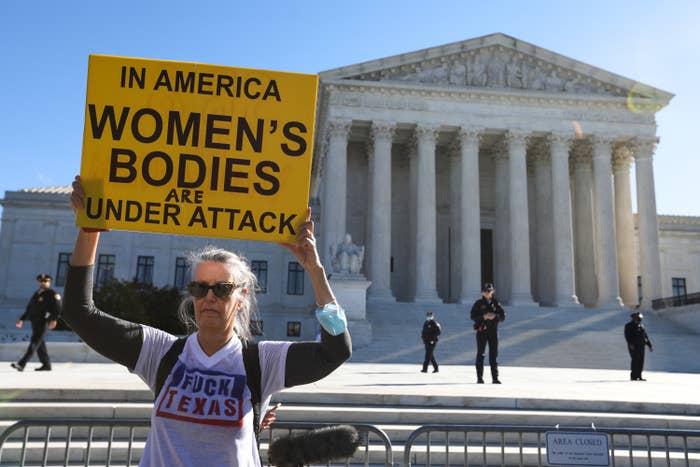

WASHINGTON — Over three hours of arguments on Monday, liberal and conservative members of the US Supreme Court came together to express skepticism that Texas could avoid any kind of sweeping constitutional challenge to its novel six-week abortion ban.

The Supreme Court won’t decide for now if the Texas law, SB 8, is constitutional. Instead, the justices are grappling with a critical threshold question: whether anyone can bring a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the law at all. Unlike other state abortion bans that failed to survive legal challenges, Texas deputized private citizens to enforce SB 8 by filing civil lawsuits against abortion providers or anyone else suspected of helping a pregnant person obtain the procedure.

The justices heard two cases on Monday: one brought by a coalition of abortion providers and one brought by the Justice Department. The state argued that the diffused enforcement structure meant no one could sue the state and that the only way to raise a constitutional challenge was as a defense after being sued. Abortion providers and the Justice Department argued Texas shouldn’t be able to get around judicial review of what was otherwise a clearly unconstitutional early-term ban under the Supreme Court’s longstanding precedents that protect access to abortion.

Most of the critical comments and questions from the court’s conservative wing came in the providers’ case, a sign that a majority of justices might be more open to letting that case go forward.

It appeared Texas had “exploited” a “loophole,” Justice Brett Kavanaugh said — and then questioned if the court should “close that loophole.” Justice Amy Coney Barrett repeatedly highlighted that Texas had structured the law so that it could never be struck down completely — that no one, in her words, could get “global relief.” Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. questioned if it was realistic to expect people to be willing to violate the law and risk steep financial penalties just so they could raise a constitutional argument in defense.

In the Justice Department’s case, on the other hand, some of the conservative justices expressed doubts about whether the federal government had the legal authority to step in and sue a state under these circumstances — especially if the court made clear in the first case that other parties could sue.

SB 8 took effect on Sept. 1. It bans nearly all abortions after fetal cardiac activity can be detected, which is typically around the sixth week of pregnancy. Pregnancy terms are counted from the first day of a person’s most recent period, so six weeks is typically two weeks after a missed period, which is when many people first realize they might be pregnant. Early-term abortion bans are often referred to as “heartbeat” laws, but that term is misleading because a fetus’s heart valves haven’t formed at that point; an ultrasound detects electrical activity.

The justices agreed to hear the case on a faster schedule, but it’s not clear when they’ll rule. They denied the Justice Department’s request to halt the law in the meantime.

Next month, the justices will hear arguments in another case out of Mississippi about whether the court should revisit decades-old precedent that says states cannot ban abortion before a fetus is considered “viable.” Viability, meaning a fetus can survive outside the womb, typically occurs around week 24 of a pregnancy at the earliest.

A win for either the abortion providers or the Justice Department would send the fight over SB 8 back down to a federal district judge in Austin. US District Judge Robert Pitman last month issued an order temporarily blocking enforcement of the law in the Justice Department’s case, but that was put on hold by the US Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit two days later, meaning the law once again took effect.

Pitman is also handling the abortion providers’ case. The 5th Circuit had paused those proceedings before he could act on a pending request for an injunction. If the Justice Department’s lawsuit doesn’t go forward, Pitman could enter another injunction in the providers’ case, or the Supreme Court could act on its own to halt the law.

The justices on Monday unpacked the law’s many unusual provisions.

Barrett probed whether anyone could ever air a full constitutional challenge to the law. She noted SB 8 included a section that placed limits on a defendant’s ability to argue that the law imposed an “undue burden” on abortion rights. She asked Marc Hearron, the lead attorney for the abortion providers, if that meant that a “full constitutional defense” could not be raised. Hearron said that was right, although it wasn’t clear how Texas courts would respond to that.

When Texas Solicitor General Judd Stone addressed the court, Barrett again questioned the lack of any way to get “global relief” from the law. She asked Stone if someone sued a potential SB 8 plaintiff to stop them from enforcing the law, whether any injunction ordered by a state court judge would only apply to that actor. Stone said that was correct.

In addition to using words like “exploited” and “loophole,” Kavanaugh also raised an issue that opponents of SB 8 hoped would get the attention of the court’s conservative justices: whether Democrat-led states could pass laws modeled on SB 8 to restrict gun rights under the Second Amendment. Kavanaugh cited a friend-of-court brief from the Firearms Policy Coalition that made this point and asked if similar laws could be passed aimed at the right to speech or religion.

Stone replied that if people were worried they didn’t have a way to bring a constitutional challenge to certain state laws, they could ask Congress to change that. Kavanaugh noted that it’d be difficult to get Congress to act on some of the subjects he’d mentioned. He raised the hypothetical scenario of a state law that said that anyone who sold an assault rifle was liable for $1 million and then left it to private individuals to enforce. Kavanaugh asked if that type of law was exempt from being reviewed by a court. Stone said yes, that it didn’t matter what constitutional right was involved.

Justice Clarence Thomas questioned the fact that SB 8 didn’t require any personal connection between the person bringing a claim in state court and the abortion at issue. A traditional tort case involved a “private matter” where one party suffers an injury, Thomas pointed out. Stone replied that an SB 8 claim could involve an “outrage” injury, prompting Thomas to say that he did not know what that was and to ask for an example.

Stone replied that a “tort of outrage” would involve “extreme moral” or psychological harm — for instance, he said, a person discovering that a close friend had obtained an abortion that violated SB 8, and that person was “invested” in the unborn child’s upbringing and state of existence.

Justices Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor offered some of the most direct criticism of the law. In response to Stone’s position that people should petition Congress if they weren’t satisfied with the current options for challenging state laws as unconstitutional, Kagan asked: “Isn’t the point of a right that you don’t have to ask Congress?”

Kagan said that the purpose of SB 8 was to “find the chink in the armor” of longstanding Supreme Court precedent that laid out how people could challenge a state law for violating the US Constitution.

“The fact that after, oh these many years, some geniuses came up with a way to evade the commands of that decision as well as … the even broader principle that states are not to nullify federal constitutional rights, and to say, ‘Oh we’ve never seen this before so we can’t do anything about it’ — I guess I just don’t understand the argument,” Kagan said.

Kagan also noted that unlike in cases where the court had to speculate about what a law would do, the fact that SB 8 had been allowed to take effect provided “a little experiment” and showed how much it would restrict abortion access across Texas.

“Here we’re not guessing,” Kagan said. “We know exactly what has happened under this law.”

Members of the conservative wing did share some concerns about how much a federal court could limit the actions of a state court. Kavanaugh said a “sticking point” for him was a 1908 decision from the Supreme Court known as Ex Parte Young, which generally held that a state could be sued in federal court for violating the Constitution. In Young, the justices concluded that state officials could be blocked from taking action, but that a federal court could not “restrain the state court from acting in any case brought before it.”

Hearron replied that a “straightforward” way for the justices to deal with Young would be to let a federal court block state court clerks from taking any action to process SB 8 claims that private individuals tried to file — that would avoid the question of whether federal judges could dictate what state judges do with cases once they’re on the docket.

The justices had sharper questions for US Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar about whether the federal government had the power to sue a state.

Thomas asked if there were any previous cases where the Justice Department had brought a similar case. Prelogar said there were not because it was the first time a state had tried to block access to the normal processes that people could use to challenge a state law as unconstitutional.

Justice Samuel Alito Jr. questioned whether the Justice Department’s position would open the door to federal lawsuits against anyone who brought a civil suit under state law — for instance, he asked, if a person brought a defamation lawsuit under Maryland law, were they “acting in concert” with Maryland? Prelogar said it wasn’t the same, since normally people sued to address a personal harm, but people suing under SB 8 were exercising the state’s interest — the fact that Texas created a $10,000 “bounty” for suing was proof of that, she said.

Justice Neil Gorsuch asked Hearron and Prelogar if they would agree that there were other types of state laws that “chill” how people exercise their constitutional rights — for instance, defamation laws that put limits on speech, gun control policies, and restrictions on how people could practice their religion in person during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Prelogar said it was true that there were other laws that had a “chilling effect on the margins, but they look nothing like this law.” Kagan then jumped in to have Prelogar clarify that the Justice Department’s argument would be the same if a state tried to adopt a similar law that chilled gun rights. Prelogar said it would.

Kagan, Sotomayor, and, notably, Barrett asked Prelogar to explain what the court should do with the Justice Department’s case if the majority found that the abortion providers’ case could go forward. Prelogar said that outcome wouldn’t fix the original violation of the government’s interests and they would still want a ruling that the federal government could bring this kind of case — but she said there might not be a need for multiple injunctions.

The court briefly heard from Jonathan Mitchell, a conservative lawyer identified by the New York Times as the architect of SB 8; Mitchell got involved in the litigation to represent private individuals who want to bring claims to enforce the law. He argued that if the federal government had a “grievance” that Texas had “found a gap” in what Congress allowed in terms of when someone could sue over a state law, officials should take that up with Congress.