Paul Manafort's former accountant testified Friday about a series of interactions she had with Manafort and his longtime associate, Rick Gates. The interactions, she said, were not always with both of them simultaneously and also ranged from questionable to potentially illegal.

Cindy Laporta, who took over as Manafort's lead accountant in 2014, said that in 2015 she agreed to go along with a plan to change numbers in Manafort's tax return based on information she did not believe was true. That change would substantially reduce Manafort's tax liability, she said. Manafort was not part of key discussions about the change that Laporta shared with the jury on Friday, but he was on other emails that referred to it.

"I very much regret it," Laporta told the jury.

Laporta was one of five government witnesses granted immunity to testify in Manafort's trial in the US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia after invoking their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. The judge asked Laporta if she was concerned she might face criminal prosecution. Yes, she replied.

Manafort is charged with underreporting his income in his tax returns, failing to report foreign bank accounts, and bank fraud. This is the first trial to come out of special counsel Robert Mueller's investigation.

Laporta's testimony Friday appeared to bolster the government's allegations that Manafort's taxes and financial dealings were rife with inaccurate information. But what exactly Manafort knew about what was going on and how involved he was in directing any allegedly illegal activity are major points of contention in the trial. His lawyers are expected to place much of the blame for any financial issues with Gates, who was originally charged with Manafort but has since pleaded guilty and agreed to cooperate with Mueller's office.

The jury on Friday saw a document prepared by Manafort's bookkeeper, who testified yesterday, listing $5.15 million in income in 2014 to Manafort's political consulting business, DMP International Inc., from an entity called Telmar Investments. Prosecutors say Manafort controlled Telmar.

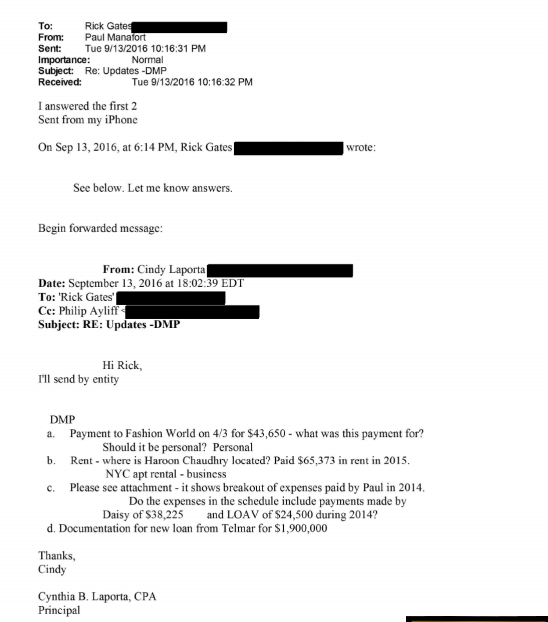

Laporta testified about a call with Gates in September 2015 about estimated taxes for DMP International for 2014 — Gates said Manafort didn't have the money to pay the amount. Another accountant and Gates discussed reclassifying income as a loan, which would mean it wasn't taxable, Laporta said. Manafort wasn't part of those discussions, according to Laporta's testimony.

The jury then saw financial documents that showed $900,000 in income from Telmar Investments being reclassified as a loan for 2014. That reduced the amount of taxes Manafort would owe by potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars, Laporta said. Laporta said Gates told her he would provide her with documents about the loan. Assistant US Attorney Uzo Asonye asked Laporta if she believed the documents would be legitimate. Laporta said no.

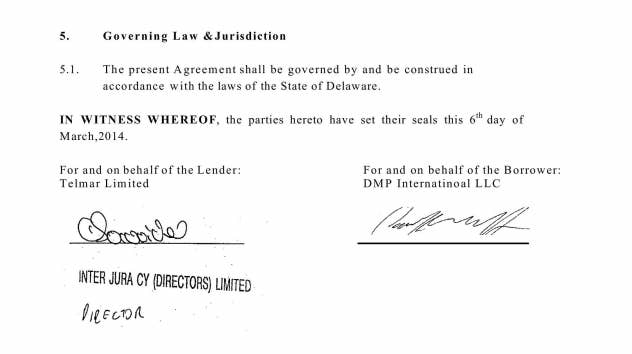

Laporta received an email from Gates with a document titled "Loan Agreement" that was dated March 6, 2014 — Laporta said she believed it was a backdated document — and purported to be an agreement for the $900,000 between Manafort's company and Telmar Investments. Laporta said the signature on the document matched Manafort's. There was no evidence Manafort made payments on that loan, she said.

Laporta said it was wrong to change these sorts of income and loan numbers after the fact. She said refusing to file the tax return could have exposed her company to a lawsuit, and she was loath to call Manafort — a longtime client — a liar.

The jury saw other emails referencing the Telmar loan that Manafort was included on. Asonye asked if Manafort ever called Laporta to ask about the loan. Laporta said he did not.

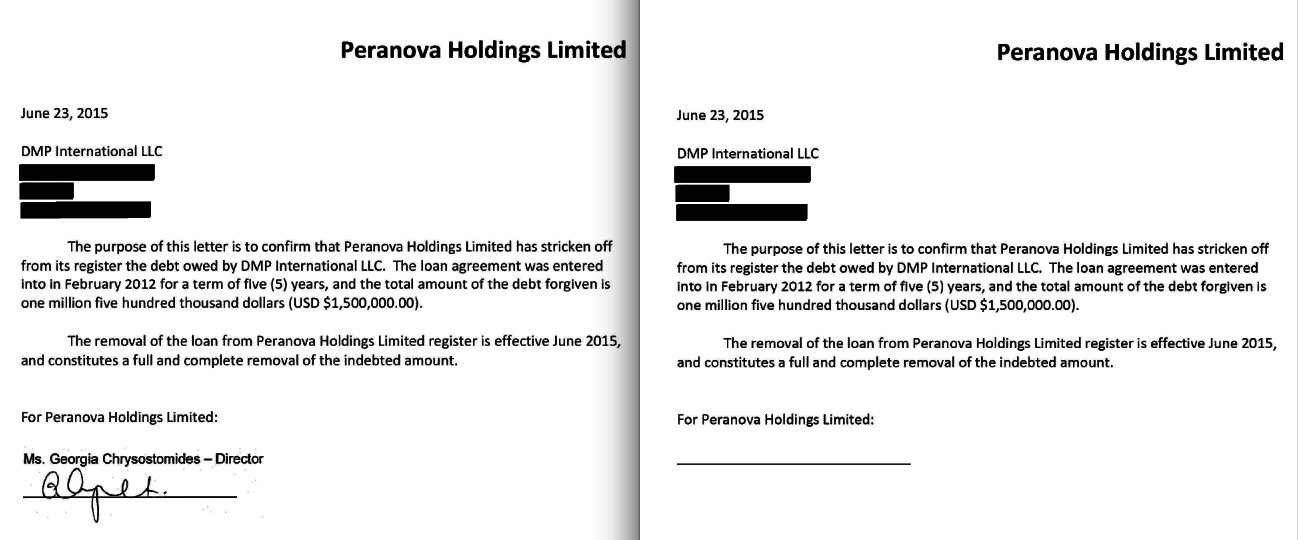

In early 2016, Laporta testified about another exchange she considered questionable. In 2012, Manafort's business recorded a $1.5 million loan from an entity called Peranova Holdings Limited. Laporta said she thought Peranova Holdings was a Manafort client; prosecutors say Manafort controlled it. As Manafort was in the process of applying for a bank loan in February 2016, the bank asked about the $1.5 million liability.

Laporta said she told the bank that the loan had been forgiven and would be reported as income — she said that either Manafort or Gates told her to say this, but she could not recall which one. Asonye asked if she believed the loan actually had been forgiven. "Uh," Laporta paused. "No."

Laporta relayed the bank's request for documentation to Gates. Gates told her that he would send a draft before chasing down signatures. Laporta testified she understood Gates's email to mean that he didn't have the document at the time. Laporta emailed Gates that it was a "good plan" to send her the draft. The judge asked her why she wrote that. She said she didn't know.

Gates then sent her a document dated June 23, 2015, on letterhead from Peranova, saying that the loan was forgiven. The document was unsigned. Laporta said she believed the document was false. The judge cut in, asking her if she still went ahead and used it even though she thought it was false. Laporta said she did. In a later email, Gates attached another version of the June 23, 2015, letter, now with a signature from a Peranova director. Laporta sent the letter to Citizens Bank.

Asonye asked why she sent the letter. Laporta said she thought the bank would vet it, and she felt protected because she hadn't prepared it.

Later in 2016, Laporta testified that Manafort told her to update a financial statement to reflect $2.4 million in income earned from work in Ukraine. Typically, his bookkeeper prepared these statements, Laporta said, but Manafort was asking to have the income recorded using an accounting method that his bookkeeper didn't use. Laporta said she agreed to make the change but didn't end up doing it because she didn't get information about the money that she asked for.

The jury saw an email that Laporta sent to a bank officer with Manafort and Manafort's bookkeeper copied, saying that Manafort expected $2.4 million to be deposited in November. Manafort directed her to send the email, she testified.

Manafort's lawyers are expected to start cross-examining Laporta on Monday.

Manafort's tax returns, revealed

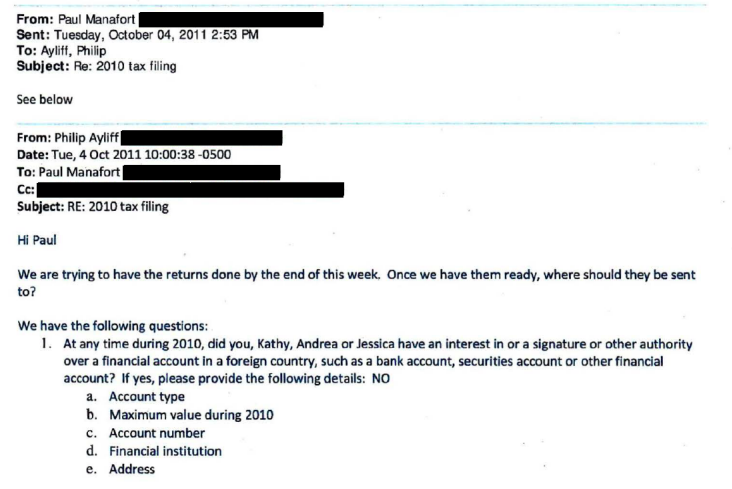

Earlier in the day, the jury saw copies of the pages of Manafort's tax returns from 2010 to 2014 that asked if he had any financial interest in overseas accounts. Each year, the form had a box checked for "no" or had "no" entered. Laporta and her predecessor as Manafort's accountant, Philip Ayliff, testified that they did not know if Manafort had overseas bank accounts — they said they believed foreign entities that transferred money to Manafort over the years were clients of his company.

The jury saw one email from Philip Ayliff to Manafort asking if he had any interest in foreign bank accounts. Manafort replied, "NO."

Ayliff and Laporta testified about exchanges they had with Manafort and Gates about how to represent Manafort's use of properties he owned to banks when he was applying for loans. Prosecutors say Manafort misrepresented his assets, debts, and other information to several financial institutions.

in January 2015, the jury saw an email from Manafort to Ayliff saying that UBS had a question about a property that Manafort owned at Trump Tower in Manhattan — whether it was being used as a rental. Manafort told Ayliff in the email that it was not a rental property and that he and his wife used it as a personal residence. But Ayliff said that did not square with what he knew and that Manafort was essentially renting the apartment from himself to use for his consulting business and had claimed business deductions in his taxes.

Ayliff said he told a UBS representative that the property was a rental. Gates was not involved in those discussions, he said.

Laporta testified telling an officer at Citizens Bank that Manafort was using a home he owned in New York City as a second residence, based on information she received from Manafort and Gates. Prosecutors presented evidence that the home was being used as a rental, however — Laporta said residences tend to get better mortgage rates from banks than rentals.

During the defense cross-examination of Ayliff, Manafort's lawyer Kevin Downing offered more hints at defense strategy to push back on the testimony so far about how loans to Manafort's business were handled. During an exchange about the $1.5 million Peranova loan, Downing asked Ayliff about balloon payments — when a loan payment is due all at once — and a reference to Peranova in one financial document as an "affiliate," which Ayliff said could indicate a relationship to Manafort.

The government also offered a few clues about what's to come next week. While the jury was out of the room, special counsel prosecutor Greg Andres told the judge there might be an issue with subpoenaed financial records they plan to enter into evidence that they received from Manafort.

Those records, which related to overseas accounts, came with a statement from Downing saying they were records that belonged to DMP International, not Gates. Andres said he planned to introduce the statement without Downing's name, but the lawyers were still figuring out if there were any conflict of interest issues that the judge would have to address, since Downing is actively representing Manafort at trial.

Documents distancing Gates from Manafort's financial records could undercut efforts by Manafort's lawyers to shift blame to Gates.