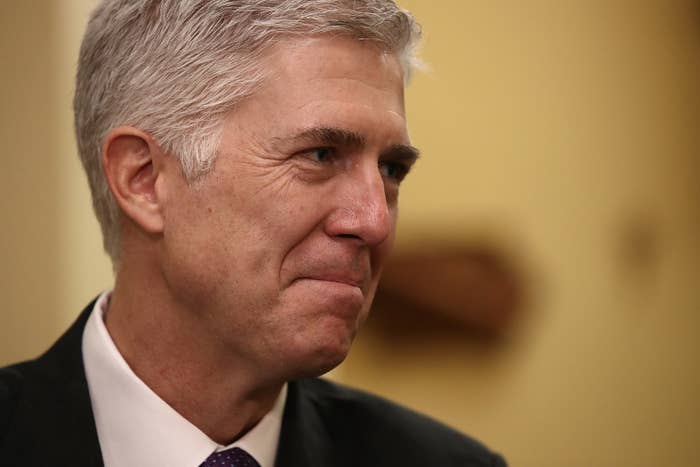

WASHINGTON — President Trump has pledged to dramatically scale back the number of federal regulations on the books. He’s found a kindred spirit in his Supreme Court nominee, Judge Neil Gorsuch, a critic of the expansion of the regulatory state who wants to revisit how much deference agencies get when they’re challenged in court.

But Gorsuch’s desire to rein in agency power also could work against Trump. Gorsuch particularly dislikes the legal doctrine known as Chevron, named after a 1984 Supreme Court opinion. That decision said courts should defer to an agency’s interpretation of a law unless it’s unreasonable.

This deference helps presidents who want to carry out their policy agenda through agency action and regulations. It also helps presidents who want to undo or loosen regulations already in place, said Jeffrey Pojanowski, a professor and administrative law expert at University of Notre Dame Law School.

“It gives power to the presidential administration whether they’re pro-regulatory or deregulatory,” he said.

Completely reversing Chevron is an extreme step that the majority of current justices are unlikely to support, said Ash Bhagwat, a professor and administrative law expert at University of California, Davis, School of Law. But Gorsuch would likely be a reliable vote to at least weaken the doctrine — steps that could have far-reaching implications for the power of the executive branch.

Without the level of deference they now receive in court, agencies facing legal challenges to how they interpret and apply federal laws would have to convince judges “they had the better of the argument,” Pojanowski said.

That could come into play if, for example, the Environmental Protection Agency under Trump tried to replace Obama-era regulations with ones that were less restrictive on industry. That was the basis for the original Chevron decision, in which the Reagan administration wanted to loosen Carter-era environmental regulations.

Environmental advocacy groups would likely go to court to fight any such deregulatory move — just as energy companies and industry groups challenged the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan, which set rules aimed at reducing air pollution from existing power plants. The Clean Power Plan case is pending before a federal appeals court in Washington, DC; it’s not clear yet what will happen to those regulations or the case under Trump.

If a case like that reached the Supreme Court with Gorsuch on the bench, it could provide an opportunity for the justices to reconsider the scope of Chevron.

Gorsuch’s thinking about Chevron differs from the established writings of the late Justice Antonin Scalia, who in a number of cases supported agency deference. (There is a debate among scholars as to whether Scalia might have been starting to rethink that position in recent years, but he had taken no clear steps toward reversing Chevron.)

Reversing Chevron and reducing the power of agencies is largely a conservative cause, nonetheless, and one that’s been backed by Republicans in Congress. Last month, the House passed the Regulatory Accountability Act, which would get rid of Chevron deference as well as another doctrine known as Auer, which calls for courts to give deference to agencies in interpreting their own regulations. The bill is now before the Senate. In 2016, Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch, a strong Gorsuch supporter, and Texas Rep. John Ratcliffe introduced similar measures, but neither the Senate nor the House bill made it out of committee.

Elliot Mincberg, a senior fellow at the liberal group People For the American Way, wrote that it was “bogus” to think that Gorsuch’s aversion to agency deference meant he could be counted on to challenge executive overreach by Trump. Mincberg pointed to cases that he believed offered proof that Gorsuch would defer to executive authority, such as a case that involved a decision by the governor of Utah to suspend funding to a Planned Parenthood state affiliate.

In that case, a three-judge appeals panel ruled against the governor, based on evidence about his motivations in suspending the funds. A majority of the full Tenth Circuit voted not to reconsider the case in 2016, and Gorsuch dissented. He wrote that the panel should have given more deference to the district court judge, who had originally ruled in favor of the governor.

Gorsuch’s dissent had more to do with how much deference appeals courts give to lower court judges, as opposed to executive power, but he did write about the “comity federal courts normally afford the states and their elected representatives.”

What is Chevron?

In Chevron USA v. Natural Resource Defense Council in 1984, the Supreme Court laid out a two-step test for how courts should handle a challenge to how an agency interprets a federal law:

Step One: Judges decide if the law at issue is ambiguous, or if the meaning of the text is clear. If they conclude it’s ambiguous, they move to step two.

Step Two: Judges decide if the agency’s interpretation of the law is reasonable. As long as it’s reasonable, Chevron says courts should defer to the agency even if the judges might have reached a different conclusion.

The thinking behind this deference to agencies is that they’re more likely to have expertise on a subject, and Congress delegated authority to agencies to interpret and carry out the laws it passes.

For anyone who thinks that federal agencies have too much power and the regulatory state is too big, though, Chevron is a problem. Gorsuch wrote in a 2016 opinion that Chevron “seems no less than a judge-made doctrine for the abdication of the judicial duty.”

The other, related, decision that bothers Gorsuch is National Cable & Telecommunications Association v. Brand X Internet Services. The Supreme Court held in that 2005 opinion that if a law was ambiguous, an agency could come up with its own interpretation even if a court had already reached a different conclusion.

Liberals who oppose Gorsuch say that reversing Chevron would make it tougher for agencies to withstand court challenges from corporate interests challenging rules and regulations that benefit the public.

Gorsuch v. Chevron

Starting in 2015, Gorsuch wrote the majority opinion a series of cases that questioned the wisdom of giving so much power to federal agencies. In October 2015, he wrote that an agency decision that overruled a court decision could only be forward-looking. People should be able to rely on whatever the law of the land is at a particular moment in time, he wrote.

“To suggest that even when you find a controlling judicial decision on point you can't rely on it because an agency (mind you, not Congress) could someday act to revise it would be to create a trap for the unwary and paradoxically encourage those who bother to consult the law to disregard what they find.”

In a May 2016 decision, he took a jab at the size of the administrative state.

“The number of formal rules these agencies have issued thanks to their delegated legislative authority has grown so exuberantly it's hard to keep up,” he wrote. Giving this authority to agencies raised “interesting” question about separation of powers and “troubling” questions about whether people could be expected to keep up with shifting agency rules, he wrote.

His frustration with agency power and how much deference agencies received in court appeared to boil over in August 2016. He wrote a concurring opinion in an immigration case that was a call to action to revisit Chevron, as well as Brand X.

“There's an elephant in the room with us today. We have studiously attempted to work our way around it and even left it unremarked,” Gorsuch wrote. “But the fact is Chevron and Brand X permit executive bureaucracies to swallow huge amounts of core judicial and legislative power and concentrate federal power in a way that seems more than a little difficult to square with the Constitution of the framers' design. Maybe the time has come to face the behemoth.”

And he concluded by presenting the way he thought “a world without Chevron” would work. Congress would continue laws for agencies to enforce, he wrote, and agencies would offer guidance about how to interpret those laws. “The only difference,” he wrote, “would be that courts would then fulfill their duty to exercise their independent judgment about what the law is.”

Would a Gorsuch vote matter on the Supreme Court?

If he’s confirmed to the Supreme Court, it’s unlikely that Gorsuch would find enough votes among the justices to completely undo Chevron, Bhagwat said. Justice Clarence Thomas would likely be on board, given his past opinions on the subject, but no other justice has come out as strongly in opposition.

Justices across the ideological spectrum have supported limiting the scope of Chevron in particular circumstances, though. In a 2015 opinion in a challenge to the Affordable Care Act, for instance, a majority of justices said that Chevron deference wasn’t appropriate on a question of “economic and political significance.”

Gorsuch would also likely be another vote in favor of revisiting the Auer doctrine, which he hasn’t written about to the same extent as Chevron, but would represent a chipping away at the latitude agencies get in court.

How much influence Gorsuch would have on issues related to agency deference is unclear. He would bring considerable administrative law experience and strong opinions on the subject, but he wouldn’t be alone. Roberts, Thomas, and Ginsburg previously served on the D.C. Circuit, which has a heavy administrative law docket. Kagan and Breyer taught administrative law before they were confirmed, with Kagan also serving as solicitor general in the Obama administration.

Still, Bhagwat said, Gorsuch joining the court “makes it more likely that Chevron would be narrowed in the future.”