WASHINGTON — BuzzFeed News is publishing a database of the hundreds of pages of documents filed in connection with the first 100 guilty pleas in connection with the Capitol riots. A close reading of these materials yields a wealth of information — not just about what the consequences look like for individual rioters who joined the mob that assaulted the Capitol, but also about the status of the larger investigation.

Plea agreements like the 100th one that Jenny Cudd of Texas entered on Wednesday show what charges prosecutors have been willing to drop (or not) in exchange for a plea, and how those decisions lower the amount of prison time a rioter is facing. They detail how much money defendants are being required to pay to cover the cost of the damage to the Capitol — anywhere from $500 to $2,000 apiece — and the fact that defendants are giving the FBI a final look at their phones and online accounts as agents comb digital records for more evidence.

The documents also show what rioters are willing to admit they did, building an uncontested record of how each person contributed to the chaos and violence that day — and what motivated them to join in the attack.

Here’s what we’ve learned from the first 100 plea deals and what to look for as the prosecution effort — which stands at more than 630 federal cases and counting — presses on.

The date

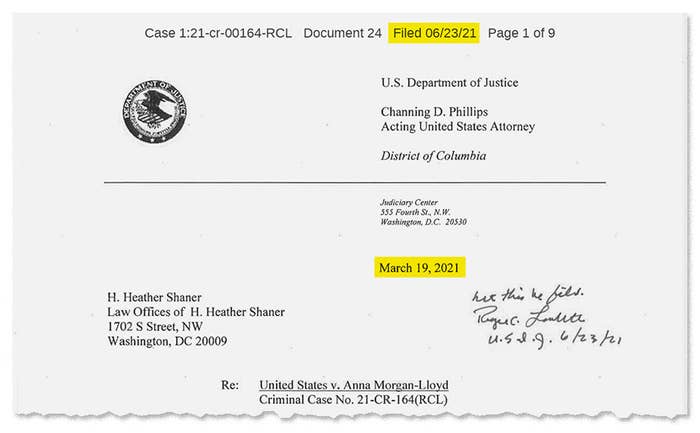

Prosecutors began revealing in court hearings in early March that they were extending plea offers to people charged in the riots. Agreements signed this summer shed light on which defendants received early offers and came forward first. Anna Morgan-Lloyd and Dona Bissey, friends who traveled together to DC from Indiana and weren’t charged with violence or more serious crimes, entered guilty pleas in June and July, respectively, to a single misdemeanor count. The offers they signed were dated mid-March.

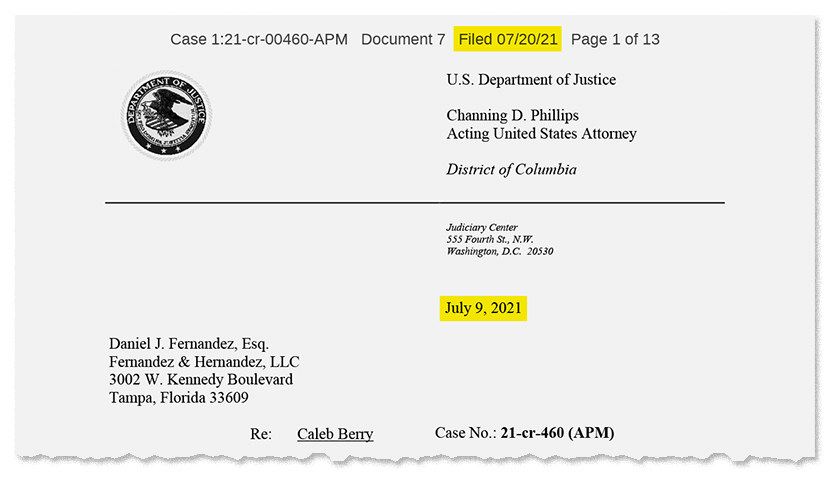

The dates in plea documents can also shed light on activities taking place out of the public eye. A plea offer letter extended to Caleb Berry of Florida was dated July 9. Berry, who pleaded guilty to being part of a conspiracy involving the extremist group the Oath Keepers, signed the deal on July 13 and agreed to cooperate with the government. Prosecutors initially filed his case under seal so he could have time to work with the government without tipping anyone off in advance of his plea hearing a week later on July 20, which is when his case — and information about his cooperation — was unsealed.

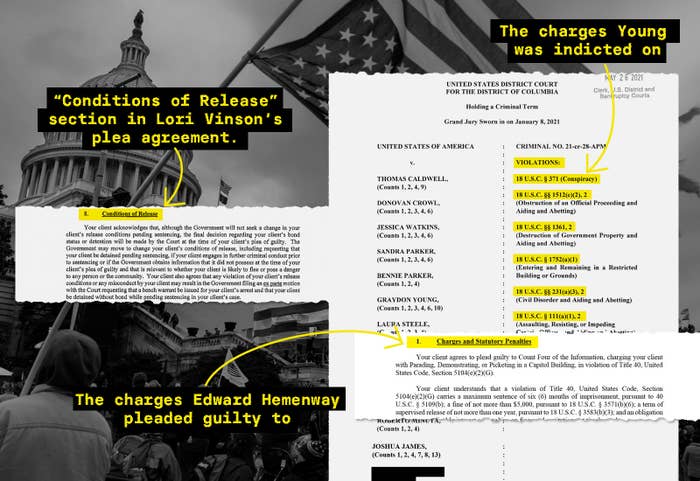

The charges

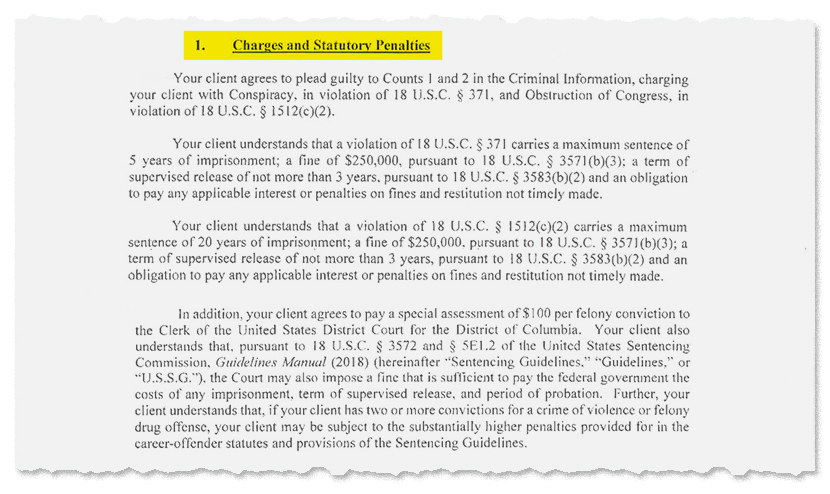

For Capitol rioters publicly charged or indicted, it’s clear what charges prosecutors dropped as part of an agreement. Graydon Young pleaded guilty to two felony counts in June: being part of the same Oath Keepers conspiracy that Berry admitted being part of and obstructing Congress. A grand jury previously indicted him for additional felony crimes, including destruction of property, civil disorder, and tampering with the investigation by deleting a Facebook account. He pleaded guilty to the most serious crimes he was charged with in terms of maximum sentences, but received credit for taking an early deal and avoided a trial on the full indictment.

Another cooperator in the Oath Keepers conspiracy case, Mark Grods, pleaded guilty to the same two charges as Young. But like the Berry case, Grods’ case was secret until his plea deal was announced on June 30 and, unlike Young, he was never indicted by a grand jury, so there’s no record of what charges he would have faced if he’d rejected the deal.

Nearly every Jan. 6 defendant, regardless of whether they’re also accused of more serious criminal activity, faces the same four baseline charges: two class-B misdemeanor counts for demonstrating in the Capitol and disorderly conduct, and two class-A misdemeanor counts for being in a restricted building and disruptive activity. The class-B crimes have maximum sentences of six months in prison while the class-A crimes carry up to a year. Most of the 100 plea deals feature a misdemeanor, not a felony. One judge has questioned the decision by prosecutors to let most rioters plead guilty to a class-B crime, since in those cases judges don’t have the authority to order longer-term court supervision.

Additional charges

The agreements explain that prosecutors can bring new charges in the future if they learn about violent conduct. Hours before Robert Reeder of Maryland was set to appear before a judge on Aug. 18 for sentencing, online sleuths working to independently identify rioters posted new footage online that appeared to show Reeder assaulting police at the Capitol. Reeder had only been charged with misdemeanor crimes, and the US attorney’s office asked to delay his sentencing to look at the new evidence. The prosecutor notified the court on Sept. 28 that Reeder wouldn’t face more charges, but that the government would bump up its sentencing recommendation from two months in prison to the maximum of six months. The judge sentenced him to three months behind bars.

Wired deals

When prosecutors extended plea deals to Erik Rau and Derek Jancart — friends from Ohio who went into the Capitol together — those offers came with a catch: Both had to take the deal, or neither of them could get it. “Wiring” is a tool prosecutors have to pressure clusters of defendants to take a deal. Four couples who were charged together and, eventually, pleaded guilty together also had wired offers.

The sentencing range

Congress sets maximum sentences for federal crimes, but the US Sentencing Commission gives judges detailed guidance to decide what’s appropriate in each case. These guidelines assign numerical values to each offense as well as other factors that might come into play, such as the severity of the crime, a defendant’s past criminal record, and whether the person accepted responsibility. Those numbers are added up and the final value corresponds to a range of recommended prison time. That range isn’t binding on judges, but they’re supposed to give it a lot of weight to keep things consistent across the criminal justice system.

These sentencing guidelines calculations help explain why people charged with the same crime in connection with the same event can face different amounts of prison time. Josiah Colt and Paul Hodgkins both pleaded guilty to obstructing an official proceeding, but Colt’s estimated range is 51 to 63 months in prison, while Hodgkins’ was 15 to 21 months. Colt, like Hodgkins, wasn’t accused of hurting anyone, but he ended up with a higher offense level because the government presented evidence that he’d planned in advance for chaos, if not violence, on Jan. 6 and played a more active role in disrupting Congress that day. Hodgkins received eight months in prison. Colt, who is cooperating, hasn’t been sentenced yet.

These sentencing calculations are where pleading guilty and doing it early can be beneficial, since those are both factors that lower a person’s final offense level.

The sentencing guidelines don’t apply to the class-B misdemeanors most Capitol riot defendants have pleaded guilty to. That means judges are free to hand down any sentence within the six-month maximum. Some rioters have received prison time, some have received home confinement, and some have received probation. In recommending sentences for a misdemeanor plea, prosecutors are parsing the details of what each defendant is accused of doing before, during, and after the riots. The government has argued for stiffer penalties for people who urged on other rioters or who didn’t express remorse after, for example.

The sentencing hearing

These agreements allow defendants to argue for a sentence below the estimated range. Hodgkins, the only person sentenced so far after pleading guilty to a felony, unsuccessfully tried to avoid prison. His lawyer argued that his conduct on Jan. 6 — making his way into the Senate chamber and walking around with a large “TRUMP” flag — was more like that of Morgan-Lloyd, who pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor and received probation. Hodgkins’ judge wasn’t persuaded, although his eight-month sentence was below the 15- to 21-month guidelines range and the 18 months that the government wanted.

Conditions of release

The vast majority of Capitol riot defendants have been allowed to go home after being charged and arrested. Once they plead guilty, whether they can stay out of jail pending sentencing is up to the judge. In misdemeanor plea deals, prosecutors have agreed to not ask judges to revoke a defendant’s release conditions. During a July plea hearing for Lori Vinson and her husband Thomas Vinson, who each pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor, US District Judge Reggie Walton briefly pondered whether jail would be appropriate now that they’d admitted participating in an “atrocious act” against democracy. In the end, he let them go home until their sentencing, but it was a brief moment of tension.

Cooperation

Seven defendants agreed to fully cooperate with investigators. Of that group, five have a connection to the Oath Keepers. Cooperation can mean anything from talking to the FBI and turning over evidence to testifying before a grand jury or at trial. It also delays sentencing so that defendants can get as much credit as possible for whatever help they give the government.

At least 60 people who pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor agreed to cooperate with the feds, too, but to a lesser extent — they’re letting the FBI take a look at anything they posted on social media about the riots or sitting for an interview. The evidence in the investigation has drawn heavily from messages, photos, and videos from Facebook, Parler, YouTube, Instagram, Twitter, and other platforms. It’s an unusual provision, since usually cooperation is all or nothing. At a plea hearing in August, one judge described the partial cooperation condition as something she’d “typically never seen, to be honest.”

Covering costs

Prosecutors have placed a price tag on the damage that rioters caused to the Capitol on Jan. 6 — $1,495,326.55 — and they’re requiring defendants who plead guilty to help cover that. In misdemeanor cases, defendants have agreed to pay $500 in restitution. In felony cases, most defendants have agreed to pay $2,000. It's ultimately up to judges to decide how much money defendants should pitch in, and they can also separately impose a fine as another form of punishment. US District Judge Trevor McFadden ordered a $3,000 fine plus $500 restitution in the case of Danielle Doyle, an Oklahoma woman who admitted climbing into the Capitol through a broken window; she pleaded guilty to the parading misdemeanor charge.

Witness protection

Jon Schaffer was the first Capitol riot defendant to plead guilty, appearing before a judge in April. He pleaded guilty to obstructing an official proceeding and entering the Capitol with a weapon; he was recorded on surveillance cameras carrying a can of what prosecutors identified as bear spray. He’d been affiliated with the Oath Keepers, and his deal included cooperation. It also included an agreement by the government to sponsor him for the Justice Department’s witness protection program if he decided it was necessary for his safety. It’s the only plea agreement to date to include that language. His status is unknown — there’s been no public docket activity in his case since his plea hearing, except for a short September order from the judge directing the parties to file a status report. His lawyer declined to comment. ●