Prosecutors followed the blockbuster testimony of star witness Rick Gates on Wednesday with a barrage of financial data presented by FBI and IRS analysts.

It was dry testimony compared to Gates' time on the stand, when Manafort's former right-hand man alleged he conspired with Manafort to commit a slew of financial crimes, admitted stealing hundreds of thousands of dollars from Manafort, and acknowledged his own extramarital affair. But numbers are at the heart of the government's case against Manafort.

Prosecutors used Wednesday's testimony to try to pull together pieces of information the jury has already heard to show the flow of money through overseas bank accounts the government says Manafort controlled.

Manafort, who served for several months in 2016 as the chair of President Donald Trump's campaign, is charged in the US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia with filing false tax returns that underreported his income by millions of dollars, failing to report his interest in foreign bank accounts, and bank fraud. It is the first trial to come out of special counsel Robert Mueller's investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election; Manafort is not charged with any campaign-related crimes.

Money coming in

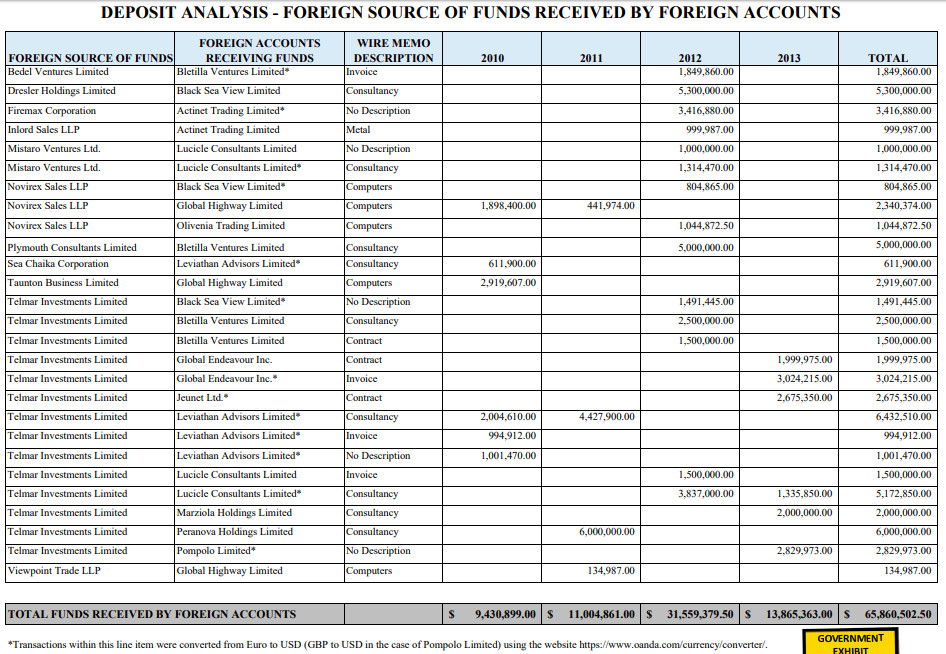

The jury saw a chart prepared by FBI forensic accountant Morgan Magionos listing 31 foreign bank accounts that she said Manafort either controlled or had a significant financial interest in. Those accounts were at banks in Cyprus, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and the United Kingdom.

The jury had heard the names of the accounts before. There was testimony from US-based vendors — men's clothing retailers, a car dealership, home contractors, and landscapers — who said they received wire transfers from these accounts to pay for services for Manafort. The vendors said they didn't know who controlled the accounts, but believed the money was coming from Manafort.

Magionos said that based on documents she received from the foreign banks, she concluded that the overseas accounts were opened by Manafort, Gates, or their Ukraine-based associate Konstantin Kilimnik. The jury saw examples of documents used to open these accounts that listed Manafort, Gates, or Kilimnik as the "beneficial owner," had at least one of their names on a signature page, or included a copy of a page from Manafort's passport.

The jury also saw emails from Manafort to a Cyprus law firm that Gates previously testified set up the overseas accounts for Manafort. In the emails, Manafort asked for wire transfers, referring to the account he wanted money sent from as "my" account.

During cross-examination, Manafort's attorney Richard Westling asked Magionos if Manafort's signatures looked different on documents used to open the overseas bank accounts. Magionos said they did. Westling asked Magionos if she knew for sure that Manafort had actually signed the documents. Magionos said she did not.

After Westling finished, special counsel prosecutor Greg Andres asked Magionos if there were differences in Manafort's signatures within a single document that Westling asked her about, which was found in Manafort's home. Magionos said she thought there were.

Magionos tallied the amount of money coming into the alleged overseas Manafort accounts. The jury saw charts she made that listed the names of accounts that made deposits, and she testified that this money was payment for Manafort's work abroad. As an example, she noted money deposited from an entity called Telmar Investments Ltd. Magionos said that entity was associated with Sergey Levochkin — the jury previously heard that Levochkin was a wealthy Ukrainian who backed Manafort's political consulting work.

The total amount of money that flowed into the alleged offshore Manafort accounts from 2010 to 2013? More than $65 million, according to Magionos's chart.

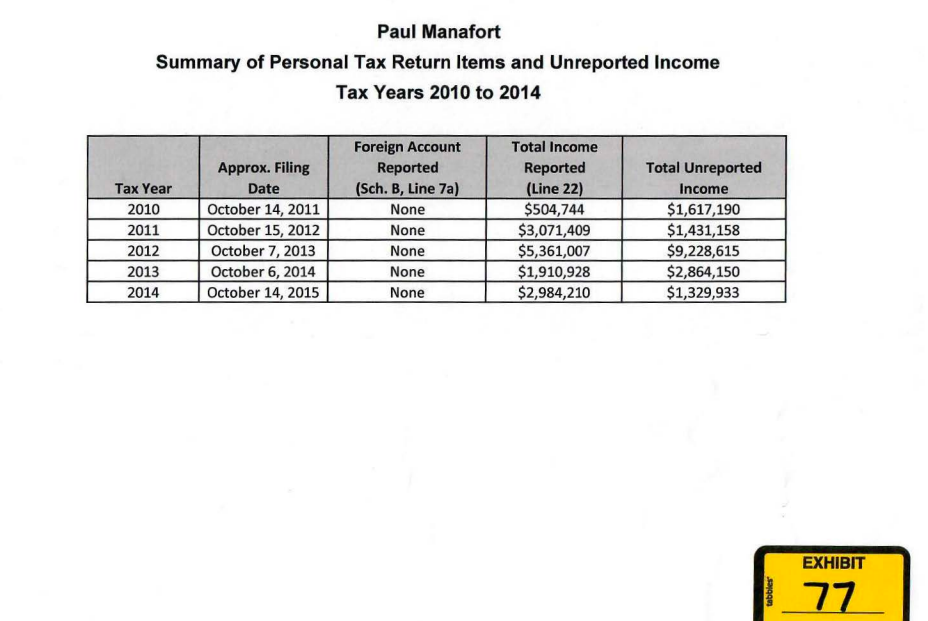

IRS audit agent Michael Welch testified Wednesday about charts he prepared summarizing bank records, wire transfers, and other financial documents associated over the past decade with Manafort, Manafort's business, and the overseas accounts at issue.

One set of charts illustrated how Welch said money flowed into alleged Manafort accounts — income from his work in Ukraine, Welch said — and then back out to Manafort's US-based business account, his personal account, and US vendors. Welch said that in tracking the path of that money, he found that some of it was reported on Manafort's tax returns. But some of it wasn't, he said. The jury saw those flow charts, but only as "demonstrative" aids, so they were not entered into the record and made available to the public.

Money going out

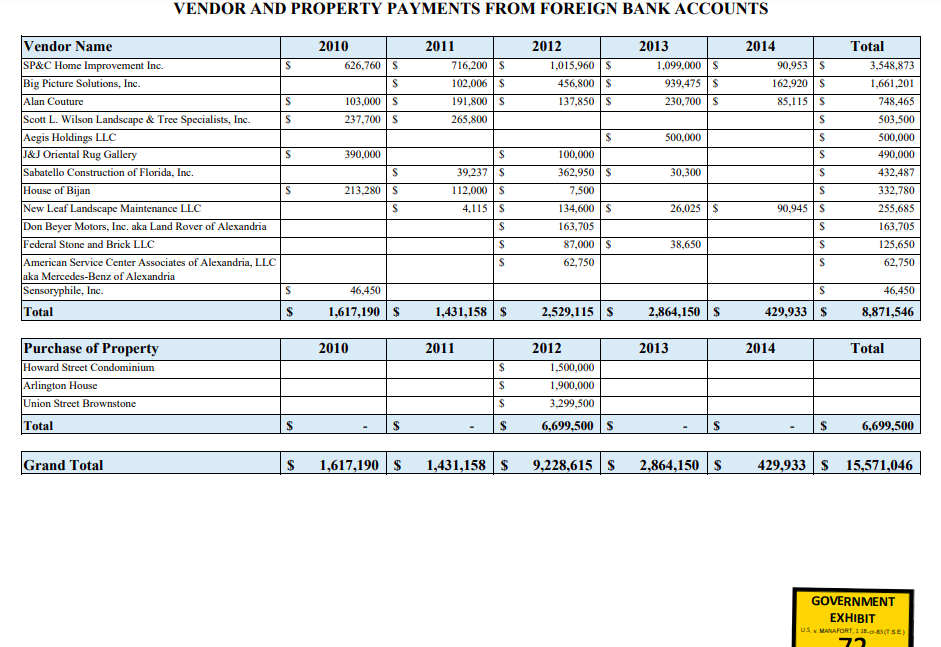

The jury saw charts Magionos prepared about money wired from the overseas accounts to pay US vendors who did work for Manafort and to buy real estate. The total payments from the foreign accounts from 2010 to 2014 — money that prosecutors say represented income earned from Manafort's work in Ukraine that he should have reported in his taxes — came to $15.5 million, Magionos said.

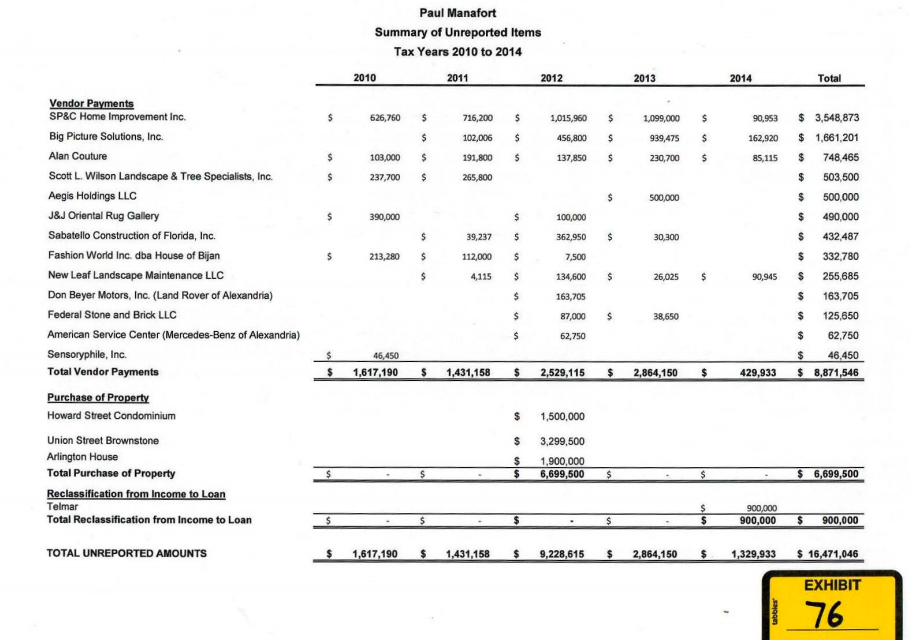

Welch presented another chart tallying what he believed was business income that flowed through Manafort's overseas accounts that wasn't reported to the IRS. From 2010 to 2014, Welch said he found $16.4 million in unreported income. That included the $15.5 million in payments that Magionos testified about, as well as $900,000 listed as a "loan" in Manafort's financial records but that Welch and other government witnesses testified was income.

Welch said his numbers were "conservative" — he said that if he didn't have supporting documents to prove that a transaction was a personal expense, he counted it as a business expense and not income. That included $45,000 that appeared to pay for dental work, according to Welch's testimony.

The jury also saw Welch's analysis of the income that Manafort did report on his personal income tax returns. From 2010 to 2014, it came to about $13.6 million, according to one of Welch's charts.

On cross-examination, Manafort's attorney Kevin Downing asked about the different ways companies can record income and whether they could spread out income over several years. Welch said they could, if the timing of the income matched the contract. Downing pressed Welch to explain how he knew all of the money coming into the overseas accounts was for Manafort's work — Welch said he had reviewed contracts, but also said he hadn't seen contracts for each deposit.

Downing asked if a company could claim a deduction in its taxes for embezzled money — a nod to Gates's earlier admission that he stole from Manafort. Welch said such a deduction was possible; when prompted about this issue later by the government, Welch said a company could only claim the deduction if the income was reported to the IRS in the first place.

Rick Gates leaves the stand

Earlier in the day, the jury heard the end of Gates's testimony. Gates was originally charged along with Manafort, but pleaded guilty in February and agreed to cooperate with Mueller's office.

During cross-examination on Wednesday, Downing asked Gates if he disclosed to the FBI during a 2014 interview the existence of offshore accounts associated with Manafort. Gates said he did. Downing asked about Gates's conversations with Manafort at the time — Gates said Manafort told him to be "open" and provide information agents wanted.

Andres questioned Gates after Downing's cross-examination and asked Gates if the IRS was part of the 2014 interview. Gates said no. Andres asked if Gates had told the FBI in 2014 that the overseas accounts contained unreported income. Gates said no.

Downing also attempted to get Gates to talk more about his extramarital activities. On Tuesday, Gates admitted to an affair but shared few details about it. On Wednesday, Gates said the relationship happened about a decade ago and lasted five months. Downing asked Gates if he had four affairs. Before Gates answered, Andres objected, questioning the relevance. Downing started to argue that it went to whether Gates was telling the truth on the stand.

The judge called the lawyers to the bench to argue further. When they returned, there was no mention of four affairs. Instead, Downing asked if Gates's "secret life" spanned 2010 to 2014. Gates replied that he had made mistakes over the years. Ellis told him to answer the question directly. Gates said yes.

"Don't try my patience"

The judge continued to push the government lawyers to speed up their presentation; Andres said Wednesday that they had eight more witnesses and were on track to finish their main presentation by the end of the week.

Amid disputes between the lawyers about what evidence and information prosecutors could show the jury on Wednesday, Ellis encouraged the lawyers to talk to each other to try to work out any issues and disclose objections before coming to the judge.

"Judges should be patient. They made a mistake when they confirmed me. I'm not very patient, so don't try my patience," Ellis told the lawyers.