WASHINGTON — President Donald Trump’s success fending off subpoenas for his tax returns and financial records hinges in part on whether his lawyers convinced the US Supreme Court on Tuesday that his situation is different from those of the last two presidents who went to court to shield records, and lost.

The Watergate and Whitewater scandals involving presidents Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton, respectively, played a starring role during three hours of telephone arguments before the Supreme Court on Tuesday in lawsuits Trump that brought, challenging demands for his records. Two of the cases involve congressional subpoenas, and the third involves a grand jury subpoena issued as part of a criminal investigation by New York District Attorney Cyrus Vance.

Trump is fighting congressional subpoenas to his accounting firm, Mazars USA LLC, and two banks he’s done business with in the past, Deutsche Bank and Capital One, for a broad swath of financial records. Vance specifically subpoenaed eight years of Trump’s tax returns, a particular political sticking point since Trump broke tradition with past presidents in refusing to make his returns public.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg asked Trump’s lawyer Patrick Strawbridge on Tuesday how the president's cases were different from those of Clinton and Nixon, noting that Clinton’s personal records and then–first lady Hillary Clinton’s law firm's billing records were subpoenaed during the Whitewater investigation, that Nixon’s White House tapes were subpoenaed as part of the Watergate investigation, and the Supreme Court ruled Clinton could face a civil lawsuit while in office.

“The aura of this case is really sauce for the goose that serves the gander as well,” Ginsburg said.

Strawbridge argued that Watergate and Whitewater were “cases of relatively recent vintage,” and that the court tends to look for a deeper historical record in considering separation-of-powers issues. He also argued that the legal fights that came out of those past scandals didn’t involve the same type of challenge to the power of a committee to subpoena documents as part of its legislative function.

Nixon's and Clinton’s legal entanglements resulted in court decisions that serve as the foundation for whatever the Supreme Court decides to do in the cases about Trump’s financial records. During the Watergate investigation, the Supreme Court ruled in 1974 that the president wasn’t entitled to immunity from a grand jury subpoena for audio tapes he’d recorded of White House conversations.

And when former Arkansas state employee Paula Jones sued former president Bill Clinton, the Supreme Court ruled in 1997 that a sitting president was not entitled to absolute immunity from a civil lawsuit related to events before he took office.

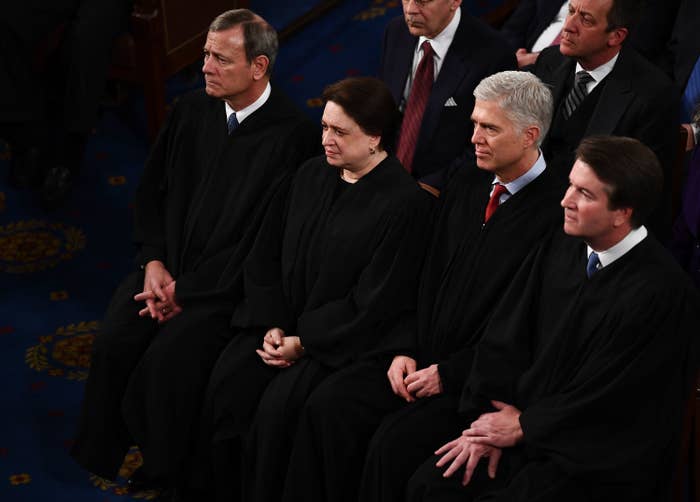

Justice Elena Kagan told Strawbridge that she was struck by the fact that Congress and presidents had fought before, but the subpoena power at issue in Trump’s cases had never come to the court in the past because the two sides had always been able to reach “accommodations.”

“What it seems to me you're asking us to do is to put a kind of 10-ton weight on the scales between the president and Congress and essentially to make it impossible for Congress to perform oversight and to carry out its functions where the president is concerned,” Kagan said.

When Strawbridge responded that the court had to “draw a line” because it was the first time Congress had tried subpoena documents of this “scale” and “scope” from a president, Kagan mused that “some former presidents” might push back on that argument.

Trump hired his own lawyers in these cases, but the Justice Department is backing him. Deputy Solicitor General Jeffrey Wall, who participated in arguments in the congressional subpoena cases on Tuesday, argued that the Supreme Court’s 1997 decision — that Bill Clinton wasn’t immune from a civil lawsuit — helped Trump because the justices said at the time that a president was still entitled to “some special protection.”

Wall argued that a congressional committee had to be more specific about its legislative goals for a subpoena to be valid. Justice Sonia Sotomayor asked what other “investigative body” was required to provide more specific information about the purpose of a subpoena than what the congressional committees gave for subpoenaing Trump’s records; the committees gave different reasons for wanting Trump’s records, including an interest in updating federal ethics laws and investigating foreign influence in the US political process.

Wall cited the Nixon case, saying the prosecutor there had to show “a specific need.” Sotomayor pushed back, noting Nixon’s case involved executive privilege concerns. Wall said that helped Trump’s argument.

“They're targeting the personal life of the president before he was a candidate for office. That raises, granted, somewhat different but deeply troubling and equally problematic constitutional concerns that you will harass—,” Wall argued before he was cut off by Chief Justice John Roberts Jr., who was enforcing time limits during the telephone arguments.

Protecting presidents

In the congressional subpoenas cases, justices from the court’s conservative and liberal wings pressed House General Counsel Douglas Letter to explain where the limit was on Congress’s power to demand documents related to a sitting president, and seemed troubled by Letter’s responses.

House Democrats have argued that committee subpoenas need only be tied to a reasonable legislative purpose, and Letter argued on Tuesday that Congress’s legislative authority was “extremely broad.” Trump and the Justice Department contend congressional committees have to be more specific about the legislative aims of a subpoena.

Roberts said he thought Letter’s “test is really not much of a test. It’s not a limitation.”

Justices Samuel Alito Jr. and Brett Kavanaugh joined Roberts’ skepticism that House Democrats’ position would protect presidents against “harassment” by Congress. Alito asked Letter: If Congress only had to show that a subpoena was relevant to some “conceivable” legislative purpose, “that’s not much protection — in fact, that’s no protection, isn’t it?” Letter replied that if a subpoena was solely intended to harass a president, members of Congress wouldn’t be able to offer a legislative reason in the first place.

Justice Stephen Breyer said he was worried about the volume of records being subpoenaed and the burden it would place on anyone, let alone a president, to review them and understand what personal information was being turned over to Congress.

“The fact that what I hold today will also apply to a future Sen. McCarthy asking a future Franklin Roosevelt or Harry Truman exactly the same questions, that bothers me,” Breyer said, referring to the late Sen. Joseph McCarthy, who used his position in the mid–20th century to launch political attacks on the Roosevelt and Truman administrations and alleged a vast conspiracy of communists infiltrating the US government.

In the case involving Vance’s grand jury subpoena, the justices asked questions that suggested they were less interested in adopting Trump lawyer Jay Sekulow’s argument that the president is protected by absolute immunity from any criminal investigation while in office. Roberts pointed out that in the case about Paula Jones’ civil lawsuit against Clinton, the justices rejected the argument that fact-gathering would be a distraction, and questioned how Sekulow could make that argument now.

Sekulow said the Clinton case wasn’t comparable because it was a civil lawsuit and the Vance case involved a criminal investigation, and because the Clinton case was filed in federal court, as opposed to state court. Gorsuch later questioned the lines Sekulow tried to draw between Trump and Clinton, wondering how subjecting a president to the full legal processes involved in a civil lawsuit was less burdensome than a subpoena for records that went to a third party — Trump’s accounting firm — and not the president directly.

Sekulow and Solicitor General Noel Francisco, who argued for the Justice Department in the Vance case, repeatedly brought up the fact that there are more than 2,300 local prosecutors in the US. They argued against empowering local officials with local interests to use state criminal investigations to go after a sitting president. Breyer countered that the Clinton case opened the door to civil lawsuits by potentially many more private litigants hoping to take a president to court, and that hadn’t stopped the court from ruling against Clinton.

Sekulow invoked the coronavirus pandemic as an example of why Trump shouldn’t be burdened with dealing with demands for his records.

“I'm going to call the president of the United States today and say, 'I know you're handling a pandemic right now for the United States, but I need to spend a couple, two to three hours with you, going over a subpoena,'” Sekulow said.

The Justice Department offered the court an alternative to Sekulow’s total immunity position, which was to require that a prosecutor go to court and set a high bar for proving that they had a special need to subpoena a president.

Carey Dunne, representing Vance’s office, agreed that courts had a role to play in reviewing grand jury subpoenas in this situation, but argued the Justice Department had the order wrong — a president should have to first prove that a request would be burdensome, and only then would a prosecutor have to show they had a special need for the information. He also offered a different standard than the Justice Department for what a prosecutor would have to show in court.

The three cases reached the Supreme Court after Trump repeatedly lost each case in the lower courts. The Supreme Court agreed in December to hear the three cases together and put on hold the federal appeals court rulings that would have required Mazars and the banks to turn over Trump’s tax returns and financial records.