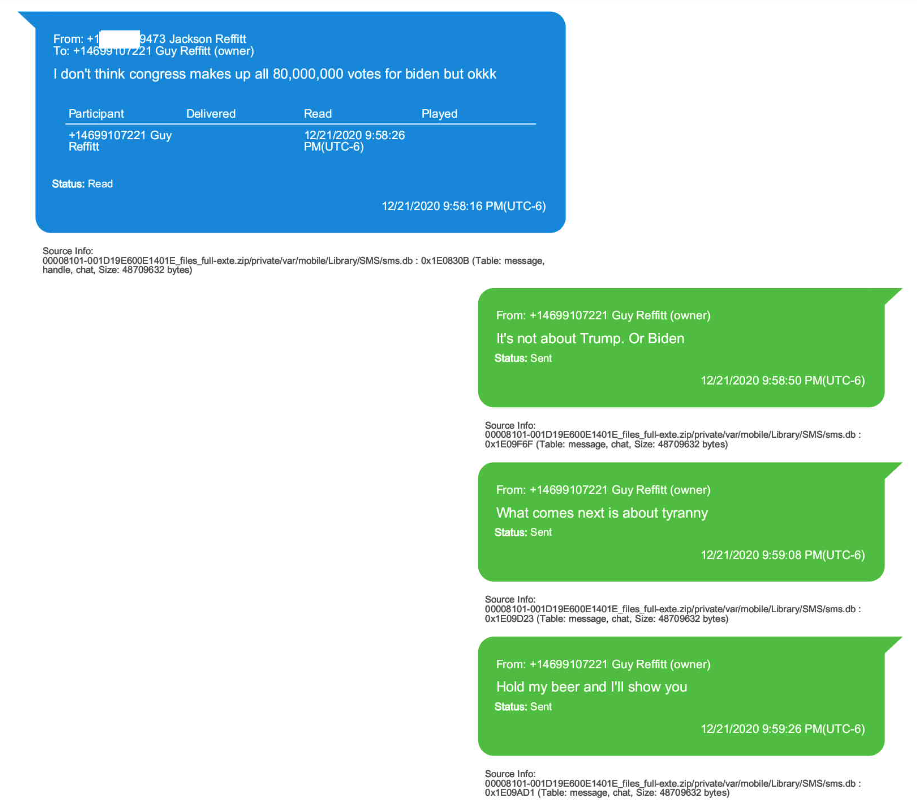

WASHINGTON — Shortly before Christmas, Guy Reffitt sent his family’s group text thread screeds about Democrats and how Congress had made “fatal mistakes.” His teenage son Jackson pushed back, writing, “I don’t think congress makes up all 80,000,000 votes for biden but okkk.”

Reffitt replied with three messages:

“It’s not about Trump. Or Biden.”

“What comes next is about tyranny.”

“Hold my beer and I’ll show you.”

Former president Donald Trump ended up being a bit player in the trial against Reffitt, which ended Tuesday with a jury finding the Wylie, Texas, man guilty of all charges in connection with his role in storming the US Capitol during the Jan. 6 insurrection; he was convicted of carrying a handgun at the time and threatening his children afterward. The jury heard only passing references to Trump and the role he played in promoting lies about voter fraud after the 2020 election, urging his supporters to come to Washington, DC, and addressing them shortly before the mob descended on the Capitol.

That could change as more cases go to trial. The government has tried to draw a line between the criminal prosecution effort, which they maintain is not about anyone’s political beliefs, and the congressional investigation and civil lawsuits that seek to hold Trump and his allies liable for the attack. But with upcoming trials featuring defendants who have a more direct connection to Trump and the “Stop the Steal” movement, or who want to argue they were following Trump’s directions, that line could start to blur.

On March 21, Couy Griffin, the founder of Cowboys for Trump, is set to appear for a one-day bench trial before a judge on misdemeanor charges that he illegally entered a restricted area outside the Capitol and engaged in disorderly conduct to disrupt government business. Video showed him overlooking the crowd from a platform on the west side of the building, and prosecutors quoted from interviews where he talked about being at the Capitol and his belief that the election was stolen.

There’s no dispute Griffin went to the Capitol — he’s talked about it on camera — but in court filings, his lawyers have questioned whether the government can prove all the elements of the charges against him. They’ve also argued that the case is politically motivated, noting that relatively few people have been charged who didn’t go inside and who weren’t involved in assaulting police on the grounds. Griffin has denounced the prosecution by “political charlatans” as an effort to “try to get to the president.”

Griffin has become a public face of the right-wing campaign to undermine the legitimacy of the criminal investigation and has continued to promote distrust about the 2020 election; he’s also reportedly been critical of Trump. Separate from Griffin’s criminal defense in court, Defending the Republic, a group led by conservative attorney Sidney Powell, produced a glossy 50-minute documentary about Griffin and his case. Powell, a driving force behind post-election voter fraud conspiracy theories, also recently represented Griffin in an unsuccessful challenge to registration and reporting rules in New Mexico for political organizations. BuzzFeed News reported that Powell's organization has covered legal expenses of at least one defendant in the conspiracy case against members of the Oath Keepers; Griffin has court-appointed counsel, which means he can't accept outside financing.

The congressional probe into Jan. 6 is exploring connections between Trump and his allies and extremist groups that had a significant presence at the Capitol, including the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys. Trials are set this year in some of the criminal cases brought against members of both groups, including the seditious conspiracy case against Oath Keepers founder Stewart Rhodes. Civil conspiracy lawsuits filed by members of Congress, police officers, and the DC attorney’s office are already testing how efforts to link Trump’s activities to the people on the ground that day will hold up in court.

Numerous defendants cited Trump as their reason for going to Washington on Jan. 6 and for marching to the Capitol after he spoke to the crowd at the “Stop the Steal” rally, according to social media posts and interview excerpts quoted by prosecutors in charging papers. In a handful of cases, people charged in the attack have petitioned judges to let them bring Trump into the courtroom, literally or via their arguments.

Dustin Thompson of Ohio, who is set to face a jury on April 11 on a six-count indictment that includes a felony offense for obstructing Congress, wants the option of calling Trump as a witness. In a brief filed last month, Thompson’s lawyer, Samuel Shamansky, wrote that they were considering a “public authority defense,” which could involve arguing that his client reasonably believed that a government official gave him permission to break the law or that he was cooperating with the government at the time.

“It is anticipated that, when called as a witness, Donald J. Trump will testify that he and others orchestrated a carefully crafted plot to call into question the integrity of the 2020 presidential election and the validity of President Biden’s victory. Moreover, it will be established at trial that Mr. Trump and his conspirators engaged in a concerted effort to deceive the public, including Defendant, into believing that American democracy was at stake if Congress was permitted to certify the election results,” Shamansky wrote.

The prosecutor in Thompson’s case urged the judge to reject the defendant’s “attempt to deflect responsibility,” arguing Thompson couldn’t show that Trump had advised him that specific criminal laws didn’t apply to breaching the Capitol and that Trump didn’t have the power to allow people to break the law. The issues that Thompson raised about Trump’s conduct were “weighty” but “irrelevant” to understanding the defendant’s intent, Assistant US Attorney William Dreher wrote. Finally, Dreher argued that even if statements by Trump were “marginally relevant,” showing video of Trump speaking that day would be the best option. The judge has yet to rule.

In December, prosecutors preemptively moved to block defendant Robert Gieswein of Colorado from arguing that Trump gave him permission to participate in the attack on the Capitol; Gieswein is charged with assaulting police using a chemical spray and wielding a baseball bat around the Capitol and entering the building through a broken window. The government argued there was “no rational claim” that Gieswein could argue he believed what he was doing was lawful regardless of what a public official said.

“Setting Defendant’s own conduct aside, it is objectively unreasonable to conclude that President Trump could authorize citizens to interfere with the Electoral College proceedings that were being conducted at the Capitol,” prosecutors wrote.

Gieswein’s lawyer replied that the defense wasn’t required to disclose if it planned to make that argument, but that Trump’s statements could be relevant to understanding his intent and they wanted to preserve his right to bring it up at trial. The judge has yet to rule. Gieswein’s trial was recently pushed back to October because of scheduling conflicts.

In late January, defendant Gabriel Garcia of Florida, a former captain with the US Army, filed a notice that he intended to raise Trump’s statements at the Jan. 6 rally urging the crowd to go to the Capitol as a defense and alluded to his military service.

“Thus, Garcia, who heard the then President’s speech above, who has no criminal history, and who is a retired military officer still subject to the Uniform Code of Military Justice, was following the orders of his Commander-in-Chief (as he followed the orders of his Commander-in-Chief, President Barak [sic] Obama while serving in Iraq) reasonably relied on then President’s assurances to lawfully walk over to the Capitol and peacefully exercise his First Amendment right to express his political grievances at the Capitol,” Garcia’s lawyer wrote.

The government hasn’t responded to Garcia’s notice yet. A trial date hasn’t been set.

Over the past year, judges have rejected similar arguments invoking Trump in the context of fights over pretrial detention and figuring out if defendants continued to pose a danger to the community. In a ruling back in February 2020, US District Chief Judge Beryl Howell wrote: “No American President holds the power to sanction unlawful actions because this would make a farce of the rule of law.”

Reffitt was the first defendant charged in connection with Jan. 6 to go to trial. The government’s case focused heavily on Reffitt’s affiliation with a local militant group, the Texas Three Percenters, and his belief that he was justified in going to Washington to physically remove what he believed were corrupt members of Congress.

The jury saw evidence that Reffitt was a Trump supporter, but it was a minimal part of the government’s presentation compared to some of his more extreme anti-government sentiments. Prosecutors displayed photos taken by the FBI at his home that showed a camouflage-print “Trump” baseball cap hanging off a corner of a bed frame and pro-Trump stickers on the back of his white pickup truck. They played parts of a Zoom conference after Jan. 6 where Reffitt wore the hat as he talked with fellow militant group members.

In a Dec. 20 message to a Telegram group of other Texas Three Percenters members, Reffitt wrote, “Our President will need us. ALL OF US…!!! On January 6th. We The People owe him that debt. He Sacrificed for us and we must pay that debt.”

But the jury also saw messages that Reffitt sent and heard him speaking in video and audio recordings about how his reasons for going to DC weren’t tied to Trump. On Dec. 22, he messaged the Texas Three Percenters: “January 6th is a Constitutional day of affliction on the American people. This isn’t about Trump. This about the corruption that has plagued our Nation for more than 50 years. Lines drawn and crossed far too many times…”

The jury watched a video during a rally at the Ellipse near the White House on the morning of Jan. 6 that Reffitt recorded from a camera attached to his helmet. A voice that the government identified as Reffitt was heard telling other people in the crowd, “This ain’t even about Trump.”

Reffitt’s defense didn’t involve Trump. His lawyer, William Welch III, focused on questioning the credibility of government witnesses and suggesting that video evidence that the government had relied on couldn’t be trusted. Welch said his client was a big talker and attempted to compare Reffitt's comments to statements by Trump and longtime Trump ally Rudy Giuliani at the "Stop the Steal" rally, but the judge sustained an objection from one of the prosecutors. He downplayed Reffitt’s confrontation with US Capitol Police officers on a stairway outside the building; prosecutors had described Reffitt as the “tip of the mob’s spear,” arguing he made the initial breach of the building possible even if he didn’t go inside. The jury returned the guilty verdict after roughly three hours of deliberating.