WASHINGTON — A federal appeals court on Tuesday invoked the recent death of George Floyd in Minneapolis in denying legal immunity to five cops in West Virginia who were sued for shooting a Black man 22 times while he lay motionless on the ground.

Judge Henry Floyd of the US Court of Appeals for the 4th Circuit wrote on behalf of a unanimous three-judge panel that to dismiss the case against officers who shot and killed Wayne Jones in 2013 "would signal absolute immunity for fear-based use of deadly force, which we cannot accept."

Floyd noted that Jones was killed a year before protests erupted nationwide after Michael Brown, an unarmed Black man, was killed by police in Ferguson, Missouri.

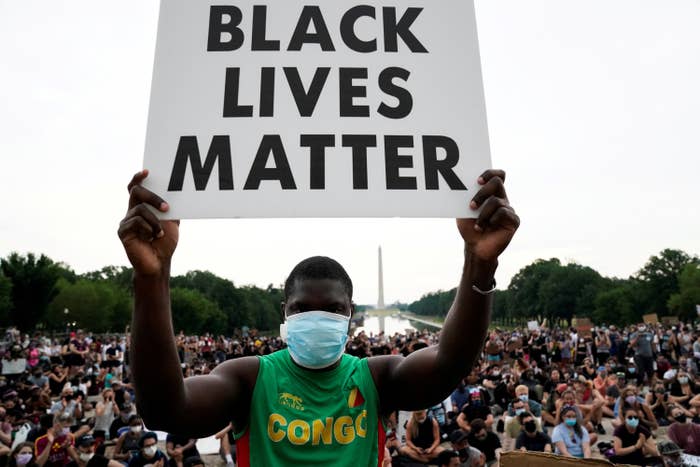

"Although we recognize that our police officers are often asked to make split-second decisions, we expect them to do so with respect for the dignity and worth of black lives. Before the ink dried on this opinion, the FBI opened an investigation into yet another death of a black man at the hands of police, this time George Floyd in Minneapolis," wrote Floyd, who is not believed to be related to George Floyd. "This has to stop."

Qualified immunity, the legal principle that has long shielded law enforcement officers and city officials from civil liability in court for excessive force and civil rights claims, has gotten fresh attention in the aftermath of Floyd's death. Floyd died after a police officer in Minneapolis used a knee chokehold on Floyd's neck for nearly nine minutes.

Federal appeals courts have struggled with how to apply qualified immunity in practice, and an ideologically diverse group of elected officials and advocacy groups is pushing the US Supreme Court to revisit the concept and get rid of it, or at least limit the circumstances when police can rely on it in court. Tuesday's opinion marks the first time a federal appeals court has explicitly linked Floyd's death with the broader debate over how much protection police should get when they're sued.

According to the 4th Circuit's opinion, Jones had been experiencing homelessness and was diagnosed with schizophrenia when a police officer in Martinsburg, West Virginia, stopped him in March 2013. Jones had been walking in the road instead of on the sidewalk, which was against state and local laws. When the officer asked if Jones had any weapons on him — Jones initially indicated he didn't know what a "weapon" was — Jones replied that he had "something."

The officer called for backup, according to the opinion. Jones tried to move away from the officers, who used Tasers on him. One of the officers said Jones hit him, and then ran away. Once the officers caught Jones, one officer used a chokehold to restrain Jones, and one could be seen on video kicking Jones on the ground. One officer then felt a "sharp poke" and saw that Jones had a knife.

According to the opinion, the officers withdrew and formed a semicircle around Jones. When the officers ordered him to drop the knife, Jones didn't respond and lay "motionless." The five officers then fired 22 shots at Jones, and he died.

A district court judge had granted qualified immunity to the officers, finding that at the time Jones was shot, he wasn't "secured" by the officers, so they hadn't used excessive force under the "clearly established" law on the issue. Under the concept of qualified immunity, whether police can get immunity for allegedly excessive or unconstitutional actions depends on whether the law was "clearly established" at the time that what they did was unlawful or unconstitutional.

But the three-judge 4th Circuit panel disagreed with the lower court judge, finding that Jones was "secured" when the officers shot him.

"A reasonable jury viewing the videos could find that Jones was secured when he was pinned to the ground by five officers," Floyd wrote. "The defendants emphasize that Jones was not handcuffed, and that, as admitted, he stabbed an officer. Yet in 2013, it was already clearly established that suspects can be secured without handcuffs when they are pinned to the ground, and that such suspects cannot be subjected to further force."

Floyd wrote later in the opinion: "If Jones was secured, then police officers could not constitutionally release him, back away, and shoot him. To do so violated Jones’s constitutional right to be free from deadly force under clearly established law."

The court said that the first officer who stopped Jones was responsible for escalating a situation that began because Jones was walking in the street instead of on a sidewalk. The fact that Jones initially refused to cooperate, and that police later discovered he had a small knife, did not give officers "carte blanche" to use deadly force.

"What we see is a scared man who is confused about what he did wrong, and an officer that does nothing to alleviate that man’s fears. That is the broader context in which five officers took Jones’s life," Floyd wrote.

Lawyers for Jones' estate and the Martinsburg police did not immediately return requests for comment.