BuzzFeed News has reporters across five continents bringing you trustworthy stories about the impact of the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Outbreak Today.

WASHINGTON — Russell Crawford, a 50-year-old father of five who lives in the Detroit suburbs, was due in court on April 8 for a hearing about his child support arrangement with the mother of his children. When the court restricted public access in March because of the coronavirus pandemic, that hearing was postponed.

Crawford, who doesn’t have a lawyer, told BuzzFeed News he was trying to figure out if there was a way to resolve the situation remotely in the meantime, or if the court would consider his case an emergency and hold a hearing. He works at a Ford automotive plant and said he was temporarily laid off during the pandemic. He said he called the court and spent four hours waiting on the phone before being transferred to the wrong unit.

Under normal circumstances, he said, he’d go to the courthouse for help. He’s anxious about trying to file on his own and doing it wrong. His fiancé tweeted at the 3rd Circuit Court of Michigan about his case, asking what it would take to get an emergency hearing, but didn’t get a response.

“You can go file, pay the money. If they find one mistake, they disregard it. So I go down there to try to get help to make sure I get everything done properly,” Crawford said.

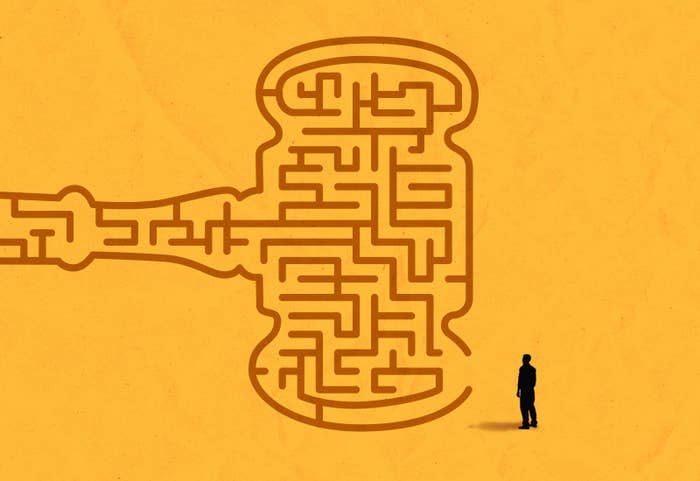

State and local court officials across the United States are scrambling to keep the civil justice system functioning while courthouses are physically closed. That includes making sure people who can’t afford a lawyer can still access the legal system, which was a challenge long before the pandemic.

The majority of people who go to court to deal with a child support dispute, to fight an eviction, or to get a restraining order against an abuser are doing it on their own. People who end up in court in civil cases do not have a constitutionally protected right to a lawyer like they do in criminal cases. At least one party in a civil lawsuit doesn’t have a lawyer in three-quarters of cases, according to a 2015 report by the National Center for State Courts, and the numbers are higher in cases more likely to involve litigants with lower incomes.

The shift to remote operations is in some ways deepening a justice gap that legal aid lawyers and judges say they could barely manage before. With courthouses closed or operating on a skeletal basis to limit the spread of the coronavirus, self-represented litigants can no longer rely on the in-person help available at courthouses, such as resource centers staffed by court employees and legal aid lawyers.

“This is the stuff that keeps me up at night. It means either people’s legal issues miraculously resolved, or people feel they don't have access to the court's processes.”

Courts are moving information and operations online during the pandemic, which is also creating barriers to access. Relying on online systems not only assumes people can figure out an electronic filing system, but also that they have a computer and internet access at home at all. Courts are turning to conference calls and video platforms like Zoom for hearings, but that still requires a computer or smartphone and assumes people can afford the internet connection or minutes needed — a problem that’s only expected to get worse as millions of Americans are out of work and struggling to pay bills.

And that's all assuming courts are providing instructions and documents in plain enough language, and in multiple languages, that litigants can figure out on their own, from home, what documents they need to file and how to do it.

“Basically the court system and legal resolution is just off the table during one of the greatest crises our country has faced,” said Katherine Alteneder, an adviser for the Self-Represented Litigation Network, a national organization of legal aid providers.

Before the pandemic, 10,000 people passed through the District of Columbia Superior Court on an average day. Chief Judge Robert Morin said that filings in civil cases are down since the court began restricting in-person access to the courthouse in March, and he fears it's because people can't figure out how to handle cases on their own from home or don’t have the technology.

"This is the stuff that keeps me up at night," Morin said. "It means either people's legal issues miraculously resolved, or people feel they don't have access to the court's processes."

Right to counsel

The pandemic has added new pressures to an already overloaded civil justice system. Most states have some type of eviction moratorium in place during the pandemic — but tenants still owe rent, and legal aid lawyers are bracing for a flood of eviction cases when the moratoriums lift. A 2015 survey of research on legal representation in housing-related cases published by the Institute for Research on Poverty found that in many courts, the landlords had lawyers and the tenants did not in 90% of cases.

In addition to the challenges that came with fighting an eviction without a lawyer before the pandemic, tenants now have to sort through federal, state, and local moratoriums during the outbreak to understand their rights, said John Pollock, coordinator of the National Coalition for a Civil Right to Counsel.

“Evictions are being filed by landlords that don’t comply with federal law, but no one is going to know that.”

A housing lawyer would know what questions to ask, what evidence a tenant needed to present to a judge, and how to find out if a landlord’s mortgage is federally backed and therefore covered by a federal eviction moratorium as well as a state one, he said.

“Evictions are being filed by landlords that don’t comply with federal law, but no one is going to know that,” he said.

Melissa Picciola, director of volunteer services at Legal Aid Chicago, said the organization is fielding phone calls from people struggling to keep up with the status of their cases as the court has delayed hearings. There was confusion at first about how people could get emergency protection orders in domestic violence cases, she said, but that got solved.

Picciola said she recently had a call with a woman who learned that her child’s father had filed a request in court to change their custody arrangement, but the woman didn’t know what the father had asked for and couldn’t access it online. The Circuit Court of Cook County makes case dockets available online, but not copies of documents.

“Normally we’d advise people, go to the courthouse, ask to see a court file,” Picciola said. “I advised her to call the clerk’s office and ask if they’ll read it to you over the phone.”

The pandemic has added a new sense of urgency to a long-simmering movement to establish a right to counsel in some types of civil cases. Last week, Rep. Joe Kennedy III, a Massachusetts Democrat, introduced a resolution to create a national right to counsel for litigants who can’t afford a lawyer in cases that involve “basic human needs, including health, safety, family, shelter, or sustenance.”

“I’m not sure you could get a more urgent moment than this one. As the last recession showed us, one of the ways in which the consequences of this amount of economic dislocation and pain manifest is through our civil courts,” Kennedy, who is running against Sen. Ed Markey this year, said.

Kennedy’s resolution acknowledges that it’s largely up to state and local governments to figure out how to make lawyers available and how to pay for it. Some cities and states have pilot projects, but the movement has been slow to spread.

Kennedy’s office said it doesn't have an estimate for how much it would cost, but cited studies showing that investment in civil legal aid saved states money in the long term; a 2014 report from the Boston Bar Association found that for every $1 invested in legal services for evictions and foreclosures, Massachusetts saved $2.69 in other costs, such as emergency shelters and healthcare.

“Who do you go to?”

The challenges that self-represented litigants face as they try to research the law and figure out court procedures on their own while courthouses are largely closed is apparent online; some people have taken to tweeting their questions at courts.

Maria Hernandez, a 44-year-old nurse in Orange, California, was helping her adult son deal with a custody fight in March when the pandemic forced the Los Angeles Superior Court to limit public access.

It was too expensive to hire a lawyer to help her and her son understand what documents they needed to file to secure visitation rights for his child and how to do it, Hernandez told BuzzFeed News. Normally, she would go to the courthouse to ask for help, but that wasn’t an option. She called the court and said she was told to check the website. She found a document that looked relevant but it said “Notice to Attorneys” at the top, so she wasn’t sure it applied.

Frustrated, she tweeted a question at the court’s account. She said she still doesn’t know what to do.

“You can’t get any answers,” Hernandez said in a phone interview with BuzzFeed News last week. “What do you do? Who do you go to?”

Jorge Alverz, a 29-year-old retail worker in Miami who said he’s out of work because of the pandemic, tweeted at the account for the Miami-Dade County court system in late April. He said he repeatedly tried calling the court for information about how to file for divorce, only to have the line disconnect each time. Alverz is in a same-sex marriage, and he told BuzzFeed News he didn’t know what to do with divorce forms he found on the court’s website that use the terms “husband” and “wife.”

Hiring a lawyer is expensive, he said, and he didn’t feel comfortable hiring someone to do something as personal as a divorce when they couldn’t meet face-to-face. He figured out how to use an online chat system the court offers, but he wasn’t satisfied when a court employee told him to use the forms with the wrong terms. He wrote his own divorce petition but hasn’t filed it yet. He said he’d prefer to go to the courthouse to do it.

“I just want to take my time and make sure I get everything right. It costs $409 to file for divorce, and even for me that’s a lot of money right now, during this time. I don’t want to lose my money filing paperwork that’s going to be rejected,” he said.

A digital divide

Judge Linda Singer Stein, the administrative judge of the County Court Civil Division for the 11th Judicial Circuit of Florida, which covers Miami-Dade County, said court officials have tried to anticipate the needs of self-represented litigants as the court system moved operations online during the pandemic. On Monday, the chief justice of the Florida Supreme Court released new guidance for judges, employees, lawyers, and self-represented litigants about procedures during the pandemic.

Courts adopted Zoom for hearings because the platform allows people to call in by telephone if they can’t do video, Stein said. Judges’ staffers are encouraging litigants they interact with to sign up for the e-filing site and sending hearing reminders by email as well as regular mail. The court is preparing to launch a system to send reminders by text message, she said.

“We are doing everything we can to make sure everyone has a full hearing,” Stein said.

At the Los Angeles Superior Court, officials have tried to make the website user-friendly; the court has a self-help phone line available on weekdays and is rolling out new online programs to help self-represented litigants like Hernandez and her son resolve custody fights and other legal issues at home.

The “digital divide” is not a new problem for the legal system, but court officials and legal aid organizations could rely on workarounds in the past, Alteneder said; even if people didn’t have a computer or internet at home, they could come to the courthouse or use a computer and printer at a public library or at a friend’s or a family member’s house. With libraries and other public buildings closed and stay-at-home orders limiting movement, however, those options have evaporated.

Courts need to confront a variety of technological shortcomings, Alteneder said, such as making sure documents can be edited on a smartphone since that may be the only way a litigant can access the internet.

Legal aid organizations that previously made lawyers available at courthouses are now figuring out how to reach people at home. In the DC Superior Court, the in-court family law resource center quickly transitioned to a telephone-based system, said Stephanie Troyer, supervising attorney for the family law and domestic violence unit of Legal Aid DC. Now, if someone calls the family court or domestic violence division at the court, they’re transferred to the resource center line. Litigants can ask questions and get forms that they can edit online, she said. If they still need a lawyer, they’re directed over to a network of legal aid attorneys.

Troyer expects the call volume to grow now that the court is allowing people to file nonemergency matters, even if judges aren’t scheduling hearings. Litigants who’ve received multiple rescheduling notices are struggling to figure out the status of their cases, said Troyer.

“There are lots of people who just don’t know what is available to them at the court,” she said.

Raun Rasmussen, executive director of Legal Services NYC, said his organization has expanded its hotline capabilities to handle a rise in demand for information about issues ranging from how to apply for unemployment benefits to confusion about delays in immigration cases.

“There’s still just a really basic lack of comprehension, lack of ability to utilize the systems that are available so that people can successfully either get benefits or get a case filed or get an order of protection filed,” Rasmussen said. “It’s just too complicated to navigate for a lot of people.” ●

If you're someone who is seeing the impact of the coronavirus firsthand, we’d like to hear from you. Reach out to us via one of our tip line channels.