WASHINGTON — On Feb. 13, Maryland State Police officers encountered Daniel Egtvedt trying to stop an older relative from leaving home to get a COVID-19 vaccine.

Another family member had called the police, fearing Egtvedt would use “physical interference,” according to court papers. Egtvedt allegedly told the officers at the time that he wouldn’t let his relative leave because of a fringe conspiracy theory that the vaccine would “eventually kill off a lot of people as a population control method from the government.”

He wasn’t arrested on the spot, but when officers ran his name, they made a discovery: Egtvedt was wanted in connection with the Jan. 6 insurrection at the US Capitol for assaulting multiple police officers, obstructing Congress, and illegally entering the Capitol. Later that day — and more than a month after the Capitol riot — he was arrested by state police and is now in federal custody.

Some Capitol rioters have made it easier for the FBI to find them than others. Court papers describe chance encounters, like the one that led to Egtvedt’s arrest, and coincidences, like an FBI agent who recognized a former classmate who posted online about storming the Capitol. A vast network of people have helped the feds so far in building cases against their friends, family members, exes, coworkers, neighbors, clients, and even fellow Trump supporters. These cases also showcase a range of law enforcement tradecraft — facial recognition software, license plate readers, cellphone tower data, search warrants to social media companies and messaging platforms like WhatsApp, and even old-fashioned stakeouts.

Egtvedt is one of more than 280 people arrested in connection with the insurrection so far, and there are hundreds more open case files as investigators sift through tips, videos, social media posts, and other evidence. Capitol Police estimate that more than 10,000 Trump supporters went onto the Capitol grounds, about 800 of whom entered the building.

Egtvedt didn’t take a selfie inside the Capitol and post it online, like a number of defendants arrested early on did, but he allegedly spoke on camera to another defendant who was livestreaming and didn’t hide his face, giving the FBI a clear photo to release in asking for tips. A witness recognized Egtvedt and contacted the bureau on Jan. 20, according to charging papers. The FBI then found public accounts under his name on Facebook, LinkedIn, Pinterest, and Twitter, and compared photos on those sites to surveillance footage, police body-worn cameras, and other videos recorded at the Capitol on Jan. 6. A criminal complaint was filed under seal on Feb. 9 (prosecutors in most cases have kept these cases sealed until they’ve made an arrest), and he was arrested four days later.

Prosecutors successfully argued to keep Egtvedt in jail while his case is pending. They described him in a detention memo as a flight risk in part because his housing situation was “unstable” — he’d lived at different addresses since Jan. 6 — and when he was arrested he was driving a different car than the one he’d taken to Washington.

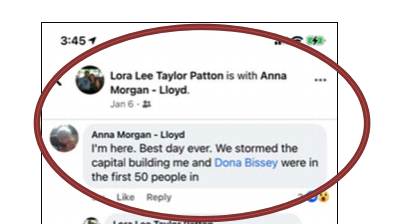

Another coincidental encounter helped the FBI identify two suspects in Indiana. Two and a half weeks after the riot, Anna Morgan-Lloyd walked into the sheriff’s office in Greene County, Indiana, to get a gun permit, according to charging papers unsealed last week. The employee processing the application recognized Morgan-Lloyd from her Facebook posts about the insurrection. The sheriff’s office gave that information to the FBI, which used it to build the case against Morgan-Lloyd and a friend tagged with her in posts from that day, Dona Bissey.

“I’m here. Best day ever. We stormed the capitol building me and Dona Bissey were in the first 50 people in,” Morgan-Lloyd wrote in a Facebook comment, according to court papers.

The government has to do more than simply identify the hundreds of people who descended on the Capitol as lawmakers met to certify the results of the presidential election. Investigators have to confirm a suspect’s identity to a degree that would convince a judge they’ve arrested the right person. They have to pull together evidence showing what exactly that person did at the Capitol. And then they have to find that person to take them into custody.

With Morgan-Lloyd and Bissey’s names in hand, the FBI found tips that witnesses had submitted about both women after the insurrection. One witness, who was later interviewed by the FBI, had visited a salon that Bissey owned over the years and said that Bissey “regularly spoke supportively of QAnon and other conspiracy theories.” The witness also turned over screenshots of Facebook posts that Bissey allegedly put up about her experience at the Capitol, including a few where she tagged Morgan-Lloyd.

“Best fucking day ever!! I’ll never forget. We got into the Capitol Building,” Bissey wrote in response to a comment on a photo she’d posted inside the Capitol, according to charging papers.

Morgan-Lloyd and Bissey are charged with illegally being at the Capitol and disorderly conduct. Their case was one of several where the government described how people suspected of participating in the insurrection went back to the minutiae of everyday life — and how that sometimes helped the investigation.

In charging documents for Clayton Mullins, an FBI agent explained that they’d found Mullins’ driver’s license thanks to a “lead” — the affidavit didn’t include details about where that “lead” came from — and used information from the license to track down a bank account under his name. The FBI interviewed a bank employee on Feb. 5 who said they’d known Mullins for around 30 years. Presented with a photo from the Capitol, the employee identified Mullins and told the FBI that he’d been at the bank just one day before the agents showed up.

Mullins’ charging papers included a screenshot from a bank surveillance camera video on Feb. 4 that showed a man standing in front of a desk, his right hand resting on top of the counter. The bank employee told the agents it was Mullins. He’s charged with assaulting a Metropolitan Police Department officer just outside the Capitol; prosecutors highlighted images from videos that they said showed Mullins “violently” pulling on an officer’s foot.

The FBI has relied on a variety of sources to identify people in videos and photos at the Capitol. In the case of Thomas Webster, a retired New York police officer and US Marine Corps veteran charged with attacking a police officer using a metal flagpole, investigators said they compared images from the Capitol with a photo Webster filed with a passport application and pictures posted by a family member on Facebook. They confirmed via a highway license plate reader that Webster’s car had traveled to Washington on Jan. 5. Finally, an FBI agent contacted an administrator at a school Webster’s children attend and that person identified Webster in photos from the Capitol.

Late last week, the government unsealed charging papers filed on Feb. 16 against Luke Coffee, a Texas man charged with using a crutch to push against a line of police officers protecting the Capitol building from rioters. The FBI fielded a number of tips identifying Coffee, according to court documents, including one from a source surprisingly close to the investigation — on Jan. 22, another FBI agent based in Washington told investigators that they recognized Coffee in Facebook posts because the two had been college classmates.

In another case, two alleged rioters were turned in by a person who had organized the bus trip they took from Pennsylvania to Washington for former president Donald Trump’s Jan. 6 rally; several passengers had complained about them. The trip organizer, who isn’t named, was friends with a person described only as a “retired law enforcement officer” and agreed to speak with that retired officer about the trip. The organizer ended up serving as a key witness in charging papers filed against Mark Aungst and Tammy Bronsburg and said that other passengers on the bus came to him with concerns about Aungst during the return ride, including that Aungst “had been intoxicated and overshared information” about going into the Capitol.

The trip organizer did a follow-up interview with law enforcement later and turned over a photograph from the bus showing Aungst with his thumbs up, as well as photos that Aungst allegedly shared with another bus passenger from inside the Capitol.

The FBI received tips identifying Christian Secor as a man seen in photographs standing in the Senate chamber, sitting in a chair on the dais, and walking elsewhere around the Capitol holding a blue “American First” flag. One tipster told the FBI that Secor — a student at UCLA, according to charging papers — moved in with his mother in California after coming back from DC and “got rid of his phone and car and bragged that he would not be caught.” To confirm those tips, the FBI said that law enforcement — it wasn’t clear if that meant FBI agents or local police — staked out his mother’s house.

“[L]aw enforcement conducted surveillance of SECOR between January 25 and 28, 2021, observing him exit his mother’s California residence and drive a vehicle registered to his father,” an FBI agent wrote in an affidavit included with his charging papers. “Based on that surveillance, law enforcement agents confirmed that SECOR appears to be the person in the photographs inside the Capitol.”

Secor is charged with being part of a mob that tried to push through a doorway blocked by police officers, as well as obstruction of Congress and illegally being inside the Capitol.

The FBI has built cases based on tips about school mascots and corporate logos spotted in images from the Capitol; in one case, FBI agents noted that a defendant was wearing a jacket with the name of his business and a phone number on the back.

Social media and cellphone activity on Jan. 6 yielded an abundance of videos, photos, and messages that prosecutors have used to build cases, as well as back-end data that investigators have used to confirm people were actually at the Capitol. After a witness reported to the FBI that they’d messaged on Facebook with Glenn Wes Lee Croy about Croy going into the Capitol, the FBI obtained Croy’s email and served a search warrant on Google for records associated with that address, according to his charging papers.

Google turned over data that the government said shows a mobile device associated with Croy’s email was at the Capitol on Jan. 6, based on location information Google collects from GPS, Wi-Fi access points, and Bluetooth signals. The witness also gave the FBI a photo that they said Croy had sent showing Croy standing with another man inside the Capitol. The government identified the other man as Croy’s codefendant Terry Lindsey, who allegedly posted the same photo on his Facebook page. Both men are charged with illegally being inside the Capitol and disorderly conduct.

The government is also relying on a process of elimination to prove who was inside the Capitol. In charging papers unsealed over the weekend for Jeremy Groseclose, who is charged with interfering with US Capitol Police trying to secure the building as well as illegally being at the Capitol, an FBI agent explained that they’d created an “Exclusion List” of mobile devices and other information that they could use to identify people who were authorized to be in the building that day. The list includes members of Congress, staff, police, “Secret Service Protectees” — a label that would apply to then–vice president Mike Pence — and medical responders.

The FBI served a search warrant on Google for records related to an email account they’d found for Groseclose. They received data placing a mobile device associated with that email at the Capitol on Jan. 6. That mobile device, an FBI agent wrote in Groseclose’s charging papers, “is not on the Exclusion List.”