A witness in Paul Manafort’s trial who handled Manafort’s applications for million-dollar loans in 2016 testified Friday that interactions between his boss at the bank — who wanted a job in the Trump administration — and Manafort made him “uncomfortable.”

Dennis Raico worked in sales at Federal Savings Bank in 2016. That year, Raico said Manafort secured two loans from the bank totaling $16 million. Raico testified that the bank’s CEO, Stephen Calk, had an unusual level of involvement in Manafort’s loans from the start, and that Raico at times was asked to serve as an intermediary between Calk and Manafort, including about the possibility of Calk serving in the campaign or the administration.

Prosecutors have argued there was a quid pro quo arrangement between Calk and Manafort — that Calk pushed through loans he knew were based on false information about Manafort’s assets in exchange for the possibility of positions with the campaign and the administration. Calk was an economic adviser to Trump’s campaign; he has not served in the administration so far. He has not been charged with a crime and has previously denied allegations of a quid pro quo deal.

Bank fraud is one of the financial crimes that Manafort is charged with in the US District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia; he’s also accused of underreporting income on his tax returns by millions of dollars and failing to report his interest in foreign bank accounts to the US government. Manafort is separately facing charges in the US District Court for the District of Columbia; that trial is scheduled to start in September.

Prosecutors closed out the second week of Manafort’s trial with testimony about the bank fraud allegations. The jury previously heard from witnesses who worked at Citizens Bank about million-dollar loans prosecutors say were only approved because Manafort inflated his income and misrepresented information about his debts and how his properties were used.

On cross-examination, Manafort’s lawyers have sought to elicit testimony placing at least some of the blame for incorrect information submitted to lenders on Manafort’s former right-hand man, Rick Gates. Gates, the government’s star witness, testified earlier in the week that he submitted false information to banks at Manafort’s direction. Gates was originally charged with Manafort, but pleaded guilty in February and agreed to cooperate with Mueller’s office.

Manafort’s trial is the first trial to come out of special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation, and Trump’s criticism of Mueller’s work has hung over the proceedings. But references to Trump have been relatively minimal compared to the amount of testimony and evidence about Manafort’s work and finances predating his time on the campaign.

Raico was one of five government witnesses granted immunity to testify in Manafort’s trial. He said Friday that when he first got the referral for Manafort’s business in April 2016, he notified Calk. Special counsel prosecutor Greg Andres asked why. Raico said Calk was “interested in politics.” The following month, Raico said he was at a dinner with Manafort, Calk, and others. The group discussed politics and the bank loans Manafort was seeking, Raico said, adding that Manafort and Calk sat next to each other.

On July 27, 2016, Raico said he had a meeting with Manafort and Manafort’s then-son-in-law Jeffrey Yohai, who was originally part of the loan application. (Yohai is now divorced from Manafort’s daughter.) Calk joined the meeting via video, Raico said, and at the end of the call, Calk said he was interested in helping Trump. Manafort’s loan application was submitted for approval the same day as the call, and was approved the next day, Raico said — he wasn’t aware of another loan approved in such a short time frame, he said.

The jury saw an Aug. 3, 2016, email from Manafort to Raico asking for Calk’s resume. Manafort was Trump’s campaign manager at the time. Andres asked Raico why Manafort wanted that. Because Calk had asked if he could help serve the Trump administration, Raico replied. Manafort left the Trump campaign several weeks later, amid scrutiny of his ties to Russia and Ukraine.

On Nov. 11, 2016 — three days after the election — Raico said he got a call from Calk. Calk told Raico that he thought he would be up for a job in the new administration, Raico said, and hadn’t heard from Manafort for a few days. Raico said Calk asked him to contact Manafort and ask if Calk was up for treasury secretary or secretary of housing and urban development. Raico said he didn’t make the call.

“It made me very uncomfortable,” Raico said.

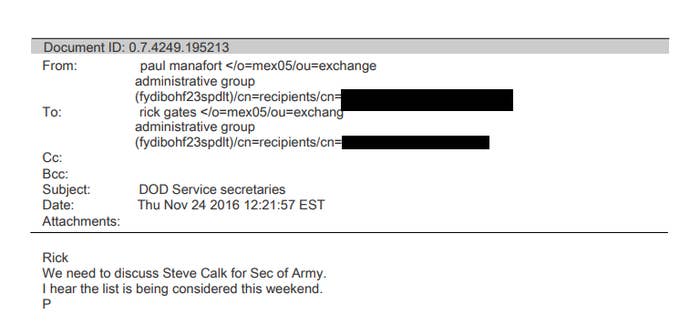

It wasn’t the first time the jury heard about Calk. Earlier this week, the jury saw an email from Manafort to Gates sent Nov. 24, 2016. Gates had worked for Trump’s inauguration committee after the election. In the email, Manafort wrote, “We need to discuss Steve Calk for Sec of Army. I hear the list is being considered this weekend.”

The jury also saw an email from Manafort to Gates, dated Dec. 23, 2016, asking Gates for inauguration tickets for a list of people that included Calk.

Manafort secured two loans from Federal Savings Bank — a $9.5 million loan against a property he owned in Bridgehampton, New York, and a $6.5 million construction loan for a property Manafort owned in Brooklyn. The Bridgehampton loan started as a construction loan to flip property in California, Raico said, but at closing, Manafort asked to change it to a cash-out loan on the Bridgehampton property — meaning he could use the money to pay down the original mortgage and also come away with cash.

The jury saw an email from Raico’s assistant to a loan underwriter saying Manafort had told her that his business’s income had “been on the up-swing” in recent years. Prosecutors have argued that this was false, and previously showed the jury documents from Manafort’s bookkeeper showing a decline in revenue since 2014, when his political consulting work in Ukraine ended.

Raico said there were issues with information coming in about Manafort’s income. He testified about an email he received from the underwriter who said the income listed on Manafort’s 2015 tax return, about $344,000, was different from the $4.4 million represented as income elsewhere.

“A plus B didn’t always equal C all the time,” Raico told the jury.

The jury also saw a document submitted to the bank that indicated Manafort's business had earned $3 million as of July 2016. Prosecutors claim this document was a fabrication. Manafort’s bookkeeper previously testified that she prepared a statement listing Manafort’s business as having a loss of more than $600,000 by July 2016, and a loss of more than $1.1 million by the end of the year. She said she did not create the document Manafort submitted to Federal Savings Bank — she noted that it had typos, was missing entries, and had a different font.

Gates testified that Manafort asked him to convert the bookkeeper’s July 2016 document from a PDF version to a Word document, which meant it could be edited. When Gates got the document back from Manafort, he said the net income had changed.

Manafort’s lawyers have asked questions about differences in how Manafort’s income could be tallied at a given time — on a cash basis, meaning counting money when it came in, versus an accrual basis, meaning including money that was earned but hadn’t actually come in yet.

On cross-examination, Manafort’s lawyer Richard Westling asked Raico if the Federal Savings Bank loans were “overcollateralized” — that the assets Manafort put up for the loan were more than the loan amount. Raico said they were. Andres then asked Raico if income was the most important factor to the bank in deciding whether to approve the type of loan Manafort sought. Raico said it was.

Manafort is also charged with lying to Federal Savings Bank about hundreds of thousands of dollars prosecutors say he owed for 2016 season tickets to the New York Yankees. Raico testified that Manafort told the bank he lent his credit card to Gates so Gates could buy the tickets, and the jury saw a memo from Gates saying that.

Later on Friday, the jury heard from Irfan Kirimca, the senior director of ticket operations for the Yankees. Via Kirimca’s testimony, the jury saw emails showing Manafort signed a five-year season ticket agreement in 2012, and that Manafort told a Yankees employee that he and his wife planned to attend opening day in 2016.

Unexplained delay

Prosecutors had told US District Judge T.S. Ellis III that they expected to finish presenting their case Friday, but that didn’t happen. At the start of the day, Ellis spent 15 minutes at the bench with the lawyers — at one point he called over a court security officer to join the conversation, which was unusual — and then recessed for about 50 minutes.

When he reconvened, he called in the jury — only to say that he was recessing again for nearly two hours. He did not explain the reason for the delay. Before the jury went out, he said he wanted to “underscore” his earlier instructions to the jury not to discuss the case with anyone and to keep an open mind about the evidence until the end of the case.

The government now expects to finish its case Monday, with two more witnesses to go, at most. One is the Federal Savings Bank underwriter involved in Manafort’s loans, James Brennan, who was granted immunity to testify. Once the government is done, Ellis will ask Manafort’s lawyers if they plan to present any evidence — they haven’t said yet if they do. If not, the case will go to closing arguments and jury instructions, and then deliberation by the jury.