In the year 2007, Donda West died and Kim Kardashian was reborn. One’s fall was not predicated on the other’s ascent; the two women never even met. But their lives are linked by Donda’s son, Kanye, whom Kim married in 2014. And their stories are funhouse mirrors of each other: different reflections of how women can attempt to reckon with the demands of beauty, and how their lives can be changed by their efforts to achieve it.

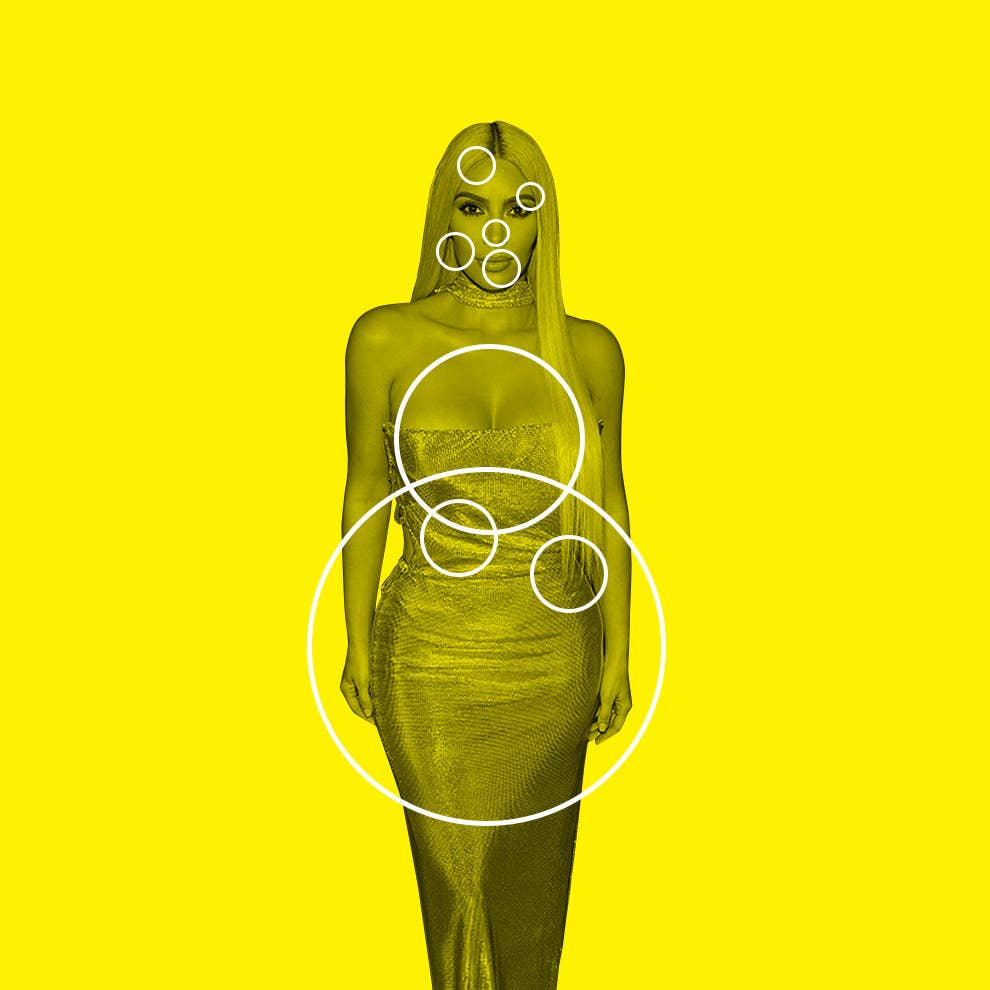

Kim Kardashian has staked her livelihood on the allure of her body, and she has staked it in part on a claim that that body is, by one particular measure, natural — that for all of her enhancements, she has never gone under the knife. Donda West died trying to improve her body, the day after receiving multiple plastic surgery procedures.

These two women’s stories illustrate the opposite ends of the spectrum in our cultural narrative about beauty. It’s a fraught subject, and a dangerous one, and you have to approach it just right, or its power will overwhelm you. If Kim can claim that beauty came for her, and not the other way around, then we understand why she’s been allowed to live with it. Donda, on the other hand, pursued beauty. She reached for it, and died in the too-tight grip of her own desire.

But that story, though culturally compelling, is just a story. In the 10 years since Donda West’s death, the technology of body modification has changed radically, birthing a host of new techniques that ride the line between procedure and surgery. These medical advances make plastic surgery seem much more approachable, but they still haven’t managed to break down its ultimate taboo.

Kim is by no means invested in proving herself to be a completely natural beauty. She is open about wearing clip-on hair extensions; she regularly Snapchats herself doing grueling daily workouts. She has been filmed — often by herself — getting Botox and receiving unspecified laser treatments from a dermatologist, and an early episode of Keeping Up With the Kardashians featured her undergoing a body-shaping treatment called VelaShape. She’s transformed her daily hours in a makeup artist’s chair into an industry, part of her actual paid work. For $2.99/month you can subscribe to watch these videos live via her app, and then you can buy the products she uses from her recently launched makeup line, KKW Beauty.

But she absolutely insists that she has never gone under the knife. Kim’s presence in the culture rides just as much on her willingness to push boundaries and break rules as it does on her ability to keep from ever seeming truly dangerous, or radical. She has an impossibly fine-tuned sense of what we will and won’t accept from her — and throughout her career, plastic surgery has remained a bridge too far.

Plastic surgery is what killed Donda West, and what had Tara Reid making headlines for “the ugliest boob job in the world.” (Reid herself called them “completely butchered.”) Plastic surgery is the line you cross where the pursuit of beauty becomes a devil’s bargain, and even the shameless, rebellious Kim Kardashian respects that narrative as an inviolable reality.

Because even as surgery and related practices evolve to become less medically dangerous, they continue to bear the cultural stigmas of effort, and violence. They remind us just how unnatural our cultural beauty standards are, as well as how consequential: It’s easy to write off makeup-obsessed girls as silly, but harder to laugh at a woman’s motivations when she’s bandaged and bleeding post-op. And ultimately, even as our ideas about women’s bodies and lives have continued to evolve over the course of the last decade, and as plastic surgery becomes increasingly acceptable, it’s still a culturally troubled topic, and old ideas about class and race continue to play outsized roles in how and on whom we’ll accept it.

On the second-to-last day of her life, Donda West had multiple plastic surgeries, among them a tummy tuck, a breast lift, and liposuction. She went home to recover under the care of her nephew, a registered nurse, against her doctor’s advice; the next day, she collapsed and was rushed back to the hospital, where she died. This was in November 2007. It would take the coroner until January 2008 to release a cause of death: “Multiple post-operative factors” was the inconclusive report. It continued: “the exact contribution of each factor could not be determined. There was no evidence of a surgical or anesthetic misadventure.”

The surgeon who had operated on her, Jan Adams, was cleared of any wrongdoing at the time, though he ultimately surrendered his medical license in 2011 after being the subject of multiple unrelated malpractice suits.

Adams’ name may have been the one in the headlines, but Kanye blames himself for his mother’s death. In a 2015 interview with Q magazine, asked what he has had to sacrifice for success, West answered: "My mom. If I had never moved to LA she’d be alive."

Kanye’s understanding of his mother’s story is a version of the classic Hollywood cautionary tale. Donda’s death seemed to have a moral: She had been struck down by her vanity. Of course Kanye believed that he was to blame. He had allowed himself to be seduced by Los Angeles’s fantasies, then, in turn, so had she.

If that kind of logic really applied — if beautiful, brash women who wanted big things for themselves were not destined to survive — Kim Kardashian certainly would have been one of its first victims. But in fact, Kim has been thriving in the public eye since 2007, the same year that Donda died. That was the year that someone (it remains unclear who) released a sex tape called Kim K Superstar, which featured Kim and her by then ex-boyfriend, a singer named Ray J, and also the year that Keeping Up With the Kardashians, her family’s reality television show, premiered on E!

Kim may not have leaked the tape that kick-started her fame, but she refused to shy away from the spotlight in its wake. In a 2012 interview she told Oprah Winfrey that she felt “humiliated” by the exposure of those intimate moments, yet she continued to expose herself — albeit on her own terms. Especially after she became a mother, Kim’s ongoing willingness to pose nude has drawn plenty of censure, as well as sparked debate around whether nudity is or can be empowering for women.

Playing with exposure and control is a standard tactic for celebrities, especially in the social media age, but it doesn’t stop the public from being infuriated by it, especially when a woman does it: when she reminds us that she has a body and a life that we want, or at least want to know about, and then reminds us that she alone controls access to both. A word Kim gets called a lot is shameless: only famous for being famous, for fucking on camera, for being beautiful and self-involved and self-promoting, and for refusing to apologize for any of these things.

The major exception to this Teflon existence is the armed robbery that took place in Kim’s Paris hotel room in October 2016. Her bodyguard was out for the evening when two masked men came in with guns; according to police reports, they tied Kim up, taped her mouth shut, and put her in her bathtub before robbing her of an estimated $5 million worth of jewelry.

Afterward, there was plenty of blame to go around, and most of it focused on Kim’s social media sharing: Karl Lagerfeld criticized her for flaunting her wealth in order to attract attention, and tabloids had security experts lining up to explain what she’d done wrong. For once, Kim agreed with them. “I was Snapchatting that I was home and that everyone was going out,” she said on an episode of Keeping Up With the Kardashians that recounted the incident, which aired five months later. “So I think they knew [her bodyguard] was out with Kourtney and that I was there by myself.”

In the aftermath, Kim took a break from public life, and when she returned, it was at first with only photos of Polaroids posted to her social media accounts — no more livecasting that would give interested parties up-to-the-minute access to her whereabouts. (Not that this matters much, when the paparazzi tail you as obsessively as they do Kim.)

But even as she increasingly keeps details of her life and her jewelry collection private, Kim has continued to allow her body to occupy the spotlight. She recently posted a nude to her Instagram account, a shot taken by a team of fashion photographers known as Mert and Marcus; it sits alongside selfies in bikinis.

Kim seems to understand the reality of her situation: Revealing certain details of her life is too dangerous. But she’s also unwilling to disappear entirely. Pictures of the body that she alone owns and controls, even still, appear on her Instagram alongside images of her cuddling with her children and husband, a stark rebuke to the notion that self-exposure can be anything more than playful, harmless provocation.

No matter how much we see of Kim’s body, the public remains convinced that it is harboring secrets. Hundreds of plastic surgeons “who have not treated Kardashian” have opined about the specifics of the possibilities of construction and amplification for her nose, cheeks, chin, lips, breasts, waist, and buttocks. Her ass has been a subject of volumes of speculation since the very beginning of her fame. Long before anyone could do side-by-side compare and contrasts of Kim’s face evolving over the course of years, people felt free to look at pictures of her butt and declare it impossible, and unnatural. Even x-rays of the asset haven’t stopped speculation.

Here’s Kim in 2013, tweeting about reports that she’d had surgery to help her lose weight after the birth of her daughter North:

I am very frustrated today seeing reports that I got surgery to lose my baby weight! This is FALSE. I worked so hard to train myself to eat right & healthy, I work out so hard & this was such a challenge for me but I did it!!! … Say what u want about me but I work hard & am the most disciplined person u will ever meet!

Kim’s words, which include three variations on the phrase “worked hard,” illuminate precisely what about the claims infuriated her. She’s not afraid to point out that she works for her looks, but for her, surgery is not work — and saying that she’s undergone it is, essentially, to accuse her of having cheated. She has earned her beauty, and, by default, the millions of dollars it brings her, which is another way of saying that she deserves her wealth and her fame. For a woman who’s constantly being accused of being famous for being famous, this is a particularly loaded position to take, and hold.

Working out is obviously active, but Kim has also happily admitted to plenty of nonsurgical “enhancement” procedures. What’s the difference? Well, during a glam session or laser treatment, she gets to remain conscious, an active participant, and that changes the optics radically — hence Kim’s technique of livecasting from her doctor’s offices, often on Instagram, Snapchat, or through her subscription-only app.

Because the other thing about plastic surgery is that it is unavoidably violent. Patients in recovery are bruised, bleeding; they look like the victims of something horrible. The premise that it is empowering or feminist to alter your body to meet a beauty standard feels easy to accept only if we don’t have to look too closely at the process by which that standard is achieved. Kim Kardashian’s beauty aims to be a NO PAIN NO GAIN slogan on a piece of athleisure, a tank top to be worn to brunch. It pays tribute to the ethic of effort, but only when combined with the aesthetic of ultimate ease.

Her public persona pushes hard on the expectations around women’s bodies and lives, bringing the labor of beauty and glam into the spotlight, and calling them labor, for which she expects to be (and now is) handsomely compensated. But that doesn’t mean she’s willing to break every boundary — in fact, her rebelliousness makes it all the more critical that she remind us that there are rules she does follow. And so, over and over and over again, she tells us that she’s never had surgery, reinforcing the notion that beauty is work, but it’s only work. It’s not violent. It’s nothing to be afraid of. See?

Despite Kim continually distancing herself from it, plastic surgery is increasingly becoming acceptable, thanks in equal part to celebs like her half sister, Kylie Jenner, 20, who regularly has Juvederm injected into her lips in order to plump them, and changes to the cosmetic procedures themselves.

Increasingly, there are many more and more subtle options available to prospective patients. Read descriptions of them, though, and it doesn’t take long for a creeping sense of dystopian doubletalk to set in. Take, for instance, this Refinery29 article about a skin-plumping procedure, microneedling, which is excerpted on the website for Beverly Hills Plastic Surgery — which is, itself, an incredible comment on the strange intersection between medicine and fashion at which these doctors sit. Microneedling “creates micro-injuries, which tell your brain to kick into repair mode. This prompts your body to send collagen to the epidermis, which, as you probably already know, is an important building block of healthy, radiant skin.” It’s surreal to see a doctor advocating injuries — no matter how micro — as a path to health.

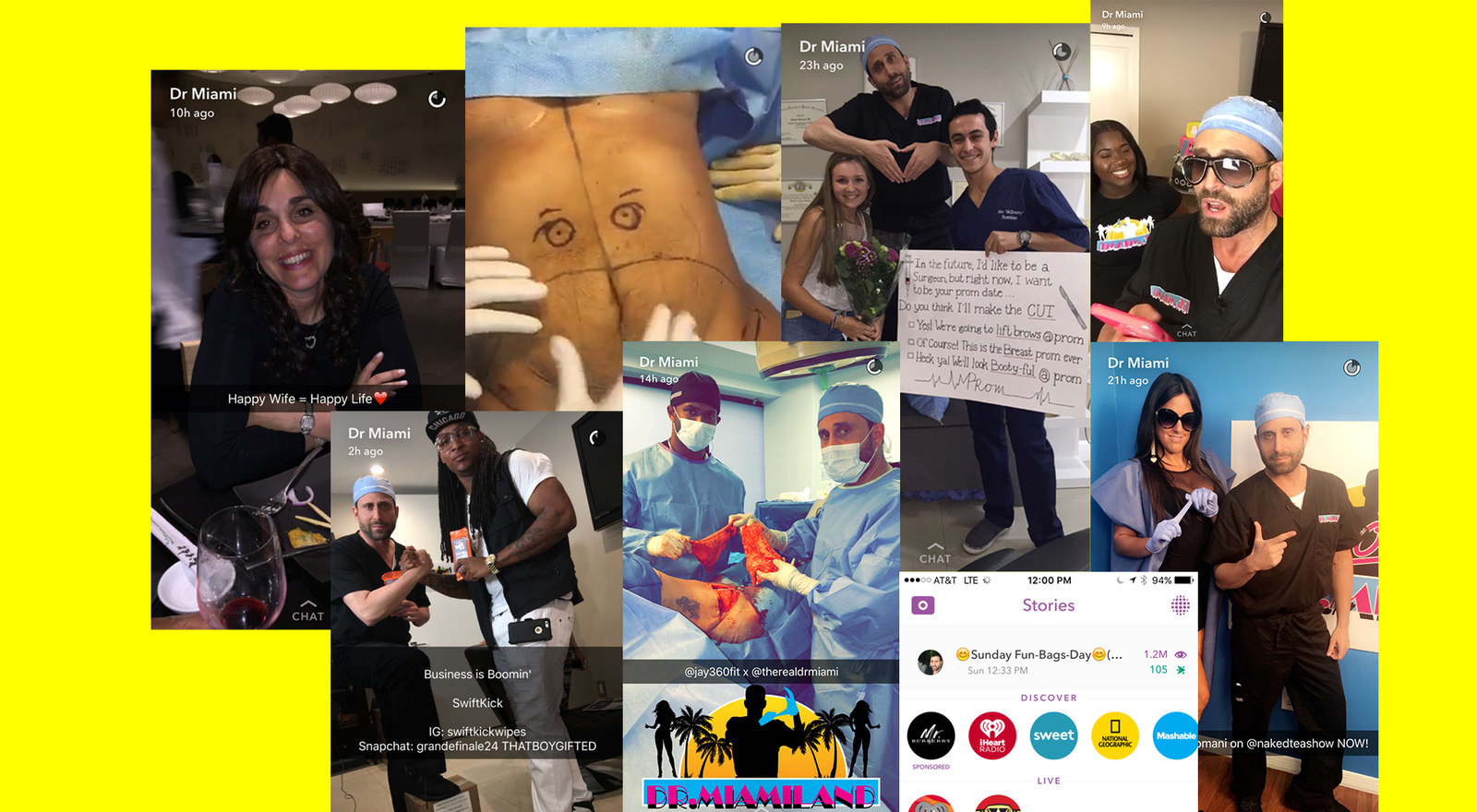

But then, these are a new breed of doctor. Plastic surgeons have started coming out of their operating rooms to drum up business the same way everyone else does: by being their own brand. The best known among them is Dr. Miami, the plastic surgeon who’s made himself famous filming his surgeries on Instagram and Snapchat. He’s parlayed those channels into a show on WeTV, which highlights his better-known clients and offers a shot at stardom of those not yet famous. He’s also appeared on other reality shows, as when he gave a labioplasty to Black Ink Crew cast member Sky.

Dr. Miami reframes the victim narrative: He calls his patients #BeautyWarriors, conferring grit and bravery on those who choose to go under his knife, suggesting not a series of desperate women trying to stave off decay but instead a tribe of girls unafraid to pursue the adventure of having a bigger, rounder ass. His from-the-table snaps are disgusting, sure, but they also demystify the surgical process, making it seem funny and raunchy rather than sterile and sad.

Dr. Miami’s willingness to be super upfront about his business suits the social media age. And in presenting himself as a self-promotional striver, he’s allowed his patients to follow suit: a young woman recently garnered enough RTs to win herself a pair of breast implants from the good doctor on Twitter.

The Dr. Miami generation of the Kardashian clan comes in the form of Kylie Jenner, whose solo reality show, Life of Kylie, debuted on E! this summer. Kylie is on a serious come-up: She was second only to Kim in terms of income in 2016, thanks in large part to her makeup company Kylie Cosmetics, which Women’s Wear Daily reported has earned $420 million in the last 18 months — $10 million in a single day when she dropped a capsule collection celebrating a recent birthday.

This is particularly remarkable when you consider that Kylie Cosmetics was launched with lip kits, a liner-and-lipstick duo that promises to give you “the perfect Kylie lip” — even though Kylie admits that hers are the result of regular injections. She denied the treatments for years before coming clean on an episode of Keeping Up With the Kardashians in 2015.

Kylie eventually told Complex magazine that she’d lied because “I didn’t want to be a bad influence. I didn’t want people to think you had to get your lips done to feel good about yourself. But they thought it was crazier that I was lying about it because it was so obvious. I wish I had just been honest and upfront.”

Kylie is a full 15 years younger than Kim, and has come of age in a totally different era of plastic surgery, both as a medical practice as well as in the public eye. Dr. Miami aside, there’s the way our definition of beauty has changed: from a look so homogenous that “every celebrity had practically the same face” to today’s #SelfLove era in which the emphasis is not precisely on looking beautiful, full stop, but on looking like the most beautiful version of yourself.

Kim is a perfect example: She insists that she wouldn’t get her nose done because she loves that its bump makes her look “ethnic,” as she told Wonderland magazine in 2016. But she did have her baby hairs on her forehead and neck lasered away (which she now says she regrets). Some features can be sold as quirks, some can be tamed into acceptability with makeup — hence Kim’s obsession with contour — and some remain unsightly, unacceptable bugs.

And Kylie’s thin lips were, as far as she was concerned, a bug. When she talks about them, she never talks about wanting to be beautiful — instead, she emphasizes wanting to like herself, repeating the story of a boy who once told her he’d thought she’d be a bad kisser because her lips were so thin. This fits with Kylie’s brand, which rides on uncertainty and insecurity: Life of Kylie largely centers on emphasizing how uncomfortable she is with certain elements of her fame, and how paparazzi presence and tabloid speculation shape her life.

In a recent video, Kylie denies rumors that she’s had a nose job, cheek and jaw reconstructive surgery, and breast implants. She lingers longest on the implants (“I’m not against it, but it’s a no for me”). It’s a canny move. Kylie is reminding us that she didn’t get plastic surgery because she wanted to be Barbie. She was just trying to tame an insecurity, and what’s more relatable than a girl who’s insecure?

The Kardashians’ fraught relationship to plastic surgery was recently crystallized when their lone brother, Rob, took to Instagram to accuse his co-parent and ex-fiancé Blac Chyna of having had $150,000 worth of postpartum surgery done on his dime when the couple was still together. (His account has since been suspended.)

“And for all [you] wondering why her nipples are so damn big that’s [because] she had surgery after the baby was born on our anniversary, Jan. 25, that I paid $150K for and they really mesed [sic] up on her nipples. Them sh-t used to be so cute and now they so damn big,” Kardashian wrote in a post.

He emphasized the costs, both financial and physical, of plastic surgery, framing it as the kind of thing messy women do to their messed-up bodies. The consensus seemed to be that Rob had been in the wrong to post intimate photos on such a public platform — Slate called him out for slut-shaming— but this didn’t stop publications like InTouch and the Daily Mail from inviting plastic surgeons to speculate further about his written claims about Chyna’s body.

Chyna has never admitted to having had any kind of surgery, before or after the birth of her daughter, Dream, but according to tabloids she’s had work done that's designed to enhance curves and give her the body that a black woman is “supposed”— or perhaps allowed — to have.

The speculation that surrounds Chyna is not exactly unjustified; also as with the Kardashian/Jenners, before and after photos suggest she may have had work done. But it’s also true that the fact that society remains obsessed with whether or not nonwhite women’s curves are “natural” or not bespeaks a deeply rooted societal racism and misogyny that insists on being allowed to investigate all women’s bodies, but particularly ones that don’t fit into a narrow-hipped white standard.

Rapper and former Love & Hip-Hop star Cardi B readily admits to having had breast implants and butt injections done when she was a teenager so that she could have a body that would give her more tips at strip clubs. She’s been able to make that body work, very literally, for her. Her past as a stripper changes the sense of shame around openly admitting to plastic surgery. She’s sold her looks before, very literally, and so it seems less taboo to admit that her body has been a site of commerce, something at least partially purchased.

Cardi B, who is of Afro-Latinx descent, is precisely the type of woman that Kim is simultaneously trying to emulate and distance herself from. Kim and her sisters mimic the aesthetic of hypersexualized black bodies while still benefiting from some amount of whiteness, which protects them from the costs that actually living in one of those bodies tends to incur. (The Kardashians sit at an uneasy ethnic intersection: Khloe, Kim and Kourtney are half Armenian, while their Jenner half sisters are fully white. Kim and co.’s looks — Kim’s nose, for instance — can code them somewhere on the spectrum of nonwhiteness. Wherever they sit, though, they are definitely not black.)

The Kardashians have long been accused of appropriating black women’s styles, making cutesy trends out of the cornrows, wigs, and extensions that have been part of black beauty culture for decades and, in some cases, centuries. They date high-profile black men almost exclusively. And they wear black bodies: Kylie’s enhanced lips are precisely the shape that black women have long been alternatively denigrated and fetishized for. Their collective celebration of the derriere comes after centuries of white obsession with Hottentot Venus–type black figures as both fascinating and disquieting in their amplitude.

The Kardashians have taken these features and styles and turned them into trends; they’ve received approbation and gotten extraordinarily wealthy in part because they can wear blackness without having to actually be black. They have increasingly gotten pushback, as in June of this year, when Kim’s team pulled an image from her KKW Beauty launch when people noted her skin was so dark that it looked like she had used her makeup to create the effect of blackface, or when black fashion designers publicly accused Khloe’s Good American and Kylie’s The Kylie Shop of ripping off their looks soon after.

But apologies aside, not much has actually changed in the Kardashian camp: Kylie and Khloe’s products are still available for purchase on their website, and just recently Kim had to apologize again, this time for defending her collaboration with makeup artist Jeffree Star, who had previously been filmed using racial slurs.

Influence is tricky to quantify; it’s somewhere between difficult and impossible to legislate taste. But it’s also true that the Kardashians seem always to be pressed up against black culture without ever having to be a part of it, or having to suffer the consequences of being born into it. They get away with this in part because they claim their bodies aren’t anything they could have planned for. They just happened to end up this way.

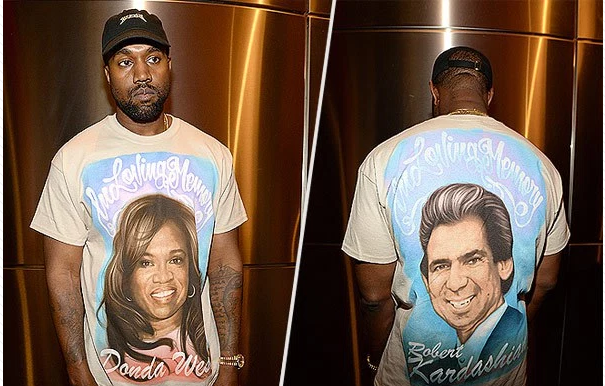

It’s been a decade, but Kanye refuses to let Donda be forgotten. When he debuted his clothing collection Yeezy Three at Madison Square Garden in early 2016, he sold merchandise: a T- shirt that memorialized her on the front, with a tribute to Kim’s late father, who died of cancer in 2003, on the back. Donda’s death and the arguments over who was to blame for it had been ugly, but it did not define the life she had lived before it. She and Robert Kardashian Sr. are two sides of the same shirt. Donda, Kanye implies, deserves as much grief as a cancer victim. And it’s notable that in People’s coverage of the shirt, Donda’s death is said to have been caused by “complications from surgery” — that it was the plastic kind is elided entirely.

Of course, it’s not possible to determine what Kanye would have said or thought about Donda’s surgery had she lived. It’s entirely possible that she would have denied having work done, if she’d had the chance. Since she didn’t, her body has been subject to intense scrutiny — but not to the judgment that would have come down on her if she had had the audacity to live.

Who hasn’t mocked a botch job? Tara Reid and Heidi Montag — they’re not dead; they just look like caricatures of themselves. We tell ourselves it’s okay to make fun of them, because they asked for it. They paid a lot of money to look that way! Whitney Houston’s implant scars were considered a matter of public interest, and released along with her autopsy after her 2012 death. (Guess which part of it made the biggest headlines.) The fact that the painkiller addiction that took Anna Nicole Smith’s life was the result of multiple poorly performed plastic surgeries never saved her from being a punchline.

Out-and-out plastic surgery has long been associated with low-class tackiness: Montag and Smith, in particular, are white, blonde women, but they also come from working-class backgrounds. Meanwhile, “having a little subtle work done” is not just condoned but expected of women of means — doing nothing and aging naturally means you’ll be accused of “letting yourself go.” Stars will admit to Botox much more readily than lip fillers, and lip fillers faster than implants of any kind.

As with so many things, it really is different if you’re white. It’s not necessarily a bad tactic, admitting to the work you’ve had done; it’s just that deploying it is easier the more privilege you have. Because admitting to your surgeries has a significant upside: If you’re willing to own them, they’re much harder to use against you. Being truly shameless precludes the possibility of being shamed.

Kim has built a brand on being shameless, but a revelation that she’d lied about surgery is one of the few things left that could truly devastate her. Her shamelessness is one of the things that sets her apart from mere mortals: Her ability to ignore and transcend the rules that govern most of our lives. How much of the magic would be lost if we discovered that not only had she built her body, but that then she’d lied to us about it after all? The myth of Kim Kardashian, specifically, is that beauty doesn’t have to hurt, and that beauty won’t hurt you.

Kim cannot betray that myth.

Ultimately, how we talk about plastic surgery is just a subset of how we talk about women who dare to live any part of their lives in public. How dare a woman allow herself to be anything less than beautiful? We ask, and then point and laugh at the ones whose pursuit of beauty goes a centimeter over the (entirely arbitrary) line of “taste.”

There’s narcotic power in rendering judgments on others; it is deeply comforting to believe that we know something someone else doesn’t, that they are dumb and helpless and we are smart, and in control. That’s the real trick here: the furious, obsessive inquiry we put into the way other people to choose to live, as if we can discover a set of rules to live by that will save us from life’s ultimate edict. We’re all gonna die, one day or another. And when that happens, we probably won’t care at all whether or not we or anyone else died pretty. ●

Zan Romanoff is a full-time freelance writer and the author of A Song To Take The World Apart and Grace And the Fever. She lives and works in Los Angeles.