Translator’s Note: Omar Khayyám (1048–1141), the subject of the short story below by Zakaria Tamer, was a Persian poet, astronomer, and philosopher, best known in the west for The Rubáiyát, a series of quatrains on pleasure, transience, and death. This passage, translated by Edmund Fitzgerald, would be familiar to schoolchildren of my mother’s generation:

“A book of verses underneath the bough

A flask of wine, a loaf of bread and thou

Beside me singing in the wilderness

And wilderness is paradise now.”

"The Accused"

by

Zakaria Tamer

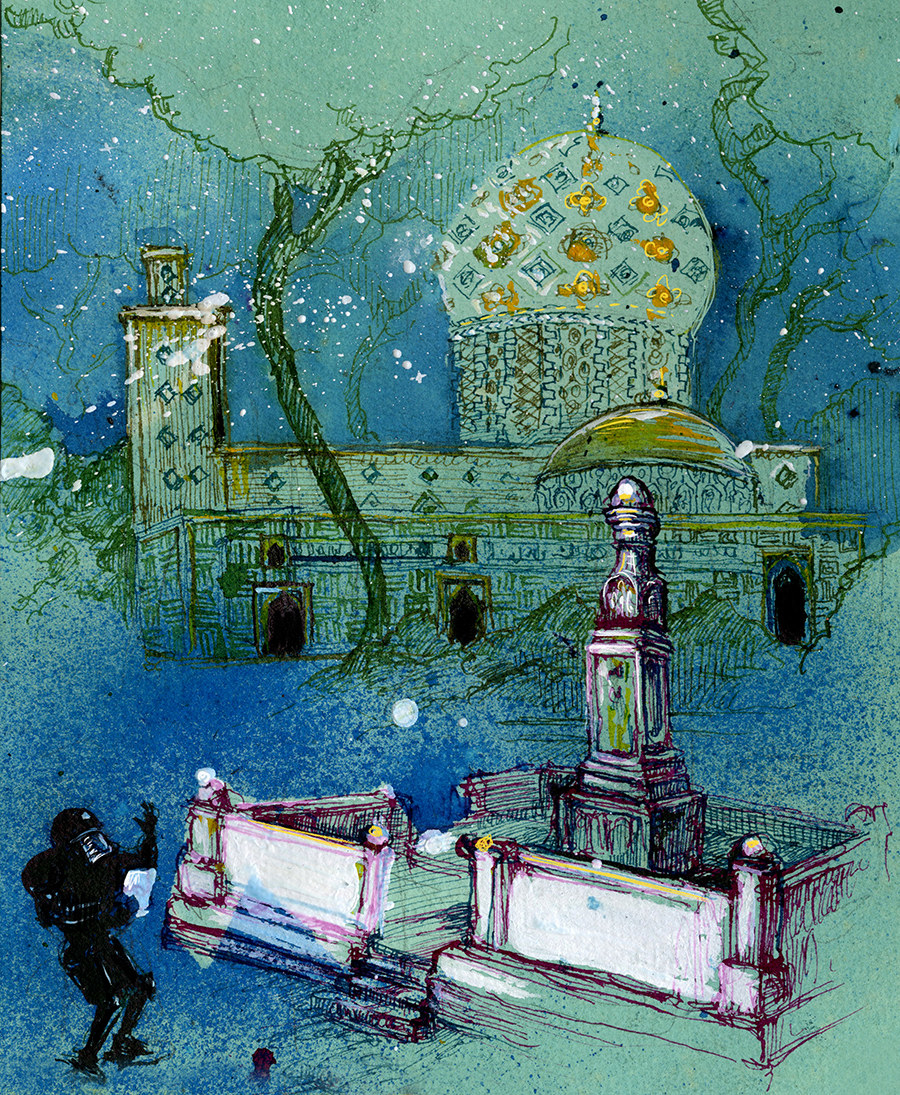

The fat policeman entered the tomb, walked a few bewildered moments, then shouted with a stretched voice: “Omar Khayyám!”

No one answered, so he took a dirty white handkerchief from his pocket, searched in its folds, balled it up, and returned it to his pocket. He shouted grouchily: “Omar Khayyám…Omar Khayyám…You are wanted to stand trial!”

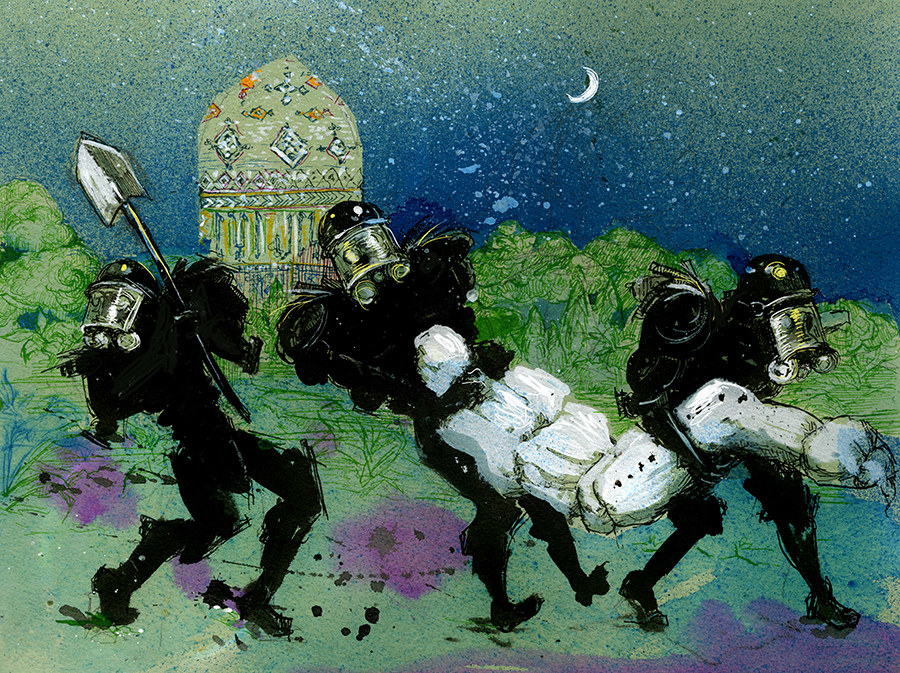

No one answered. The policeman left the tomb and returned to the police station. There, he wrote a report on the events, stressing Omar Khayyám’s refusal to appear in court. He presented his report to his bosses, who scowled in denial and shock. They began to issue orders. They immediately dispatched a number of policemen to the tomb, each carrying a shovel and pickax, and the policemen dug up Omar Khayyám’s grave. They brought Khayyám out from beneath the soil — drooping, dusty, and worn of flesh — and carried him to the courtroom, where he appeared before the judge.

The judge said in a sedate and friendly tone: “You, oh, Omar Khayyám, are accused of writing poetry that praises — and calls for the drinking of — wine. Our countries aspire toward economic independence, thus our laws forbid the importation of foreign goods. Since our countries lack the ability to manufacture wine, your poetry constitutes an incitement of demand for foreign goods — something the law punishes without hesitation. Do you admit and recognize your guilt?

“Why do you not answer? Talk! Silence is unwholesome. Okay. Your silence indicates that you deny the accusation. Well, since justice is our purpose, we’ll attempt to know your innocence or guilt. Or, if not…one who writes poetry must be proficient in reading and writing. Are you good at reading and writing?

“Do you deny this? Then we will call witnesses.”

The first witness (owner of a bookshop): “The accused bought a large number of books from my bookshop.”

The judge: “What type of books did he buy?”

The first witness: “He bought various types of books, but his favorite were books that talked about love.”

The judge: “Haha! So he liked sex books?!” God have mercy upon good morals! Tell me, didn’t he buy political books?”

The first witness: “Political books?! I swear that never, for a single day, have my hands touched a book of politics. Perhaps he was buying them from another bookstore.”

The judge: “So, he was buying books.”

The first witness: “He also bought white paper and pens.”

The judge: “God is great! Falsehood is defeated, and Right prevails. The accused didn’t merely know reading and writing, but he spent money on pens, paper, and books.”

The second witness (an old woman): “All I know about the accused is that he loved nothing but words. A woman told me she had loved him, and that he showed her he loved words more than the most beautiful woman in the world.”

The judge: “He loves words?! Oh, he’s a pervert! A healthy citizen only loves his mother and the government.”

The third witness (a journalist): “I’ve checked out the accused’s poems, and found that they lack any praise for the goodness of the government.”

The judge: “This is decisive proof that the accused does not love The People.”

The fourth witness (a man with a long beard): “I swear by God that I heard, with my two ears (which will be eaten by worms after my death), I swear that I heard the accused say that wine defeats Sadness.”

The judge: “This testimony is becoming very serious since it proves to the court that Sadness is spreading among the people.”

The fifth witness (the chief of the police station): “Many reports were returned to us about the destructive activity engaged in by this alleged Sadness, but, until now, we have not been able to arrest him, and our investigation is still ongoing.”

The sixth witness (a prisoner): “Sadness seduced me to demand a free life.”

The seventh witness (a prisoner): “Sadness forced me to curse the government.”

The eighth witness (a prisoner): “Sadness pushed me to participate in a demonstration.”

The ninth witness (a prisoner): “Sadness incited me to try to escape from prison.”

The tenth witness (a prisoner): “Sadness made me hate police.”

The judge: “The witnesses’s statements prove that Omar Khayyám’s poetry not only explicitly calls for wine and the importation of foreign goods, but also carries out a suspicious plan aimed at inciting riots. The witnesses’s statements also prove that Omar Khayyám supports Sadness, who is, the court states, nothing but a fifth-column spy who serves our enemies in order to disturb security and provoke unrest.”

For a while, the judge remained silent, his gaze full of comfort and bliss. Then he resumed his speech, and sentenced Omar Khayyám to a total ban on writing poetry.

The policemen brought Omar Khayyám to his tomb, returned him to his hole, and heaped soil over him. Afterward they destroyed what they owned of pens and paper. But Sadness remained free to pursue his destructive activities. ●

Zakaria Tamer was born in 1931 in Damascus. He left school at age 13 to help support his family, and subsequently educated himself. He has written in a variety of forms, from satirical newspaper columns to children’s books, but the genre for which he is best known is al-qissa al-qasira jjiddan, the very short story. A former editor of al-Ma’rifa, a magazine published by the culture ministry, he was fired in 1980 for publishing pro-freedom content. He exiled himself from Syria and immigrated to the UK, where he lives today.

Molly Crabapple is an artist, journalist, and author of the memoir, Drawing Blood. Called "An emblem of the way art can break out of the gilded gallery" by the New Republic, she has drawn in and reported from Guantanamo Bay, Abu Dhabi's migrant labor camps, and in Syria, Lebanon, Gaza, the West Bank, and Iraqi Kurdistan. Crabapple has written for publications including the New York Times, Paris Review, and Vanity Fair. Her work is in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art. She is currently working with Syrian journalist Marwan Hisham on Brothers of the Gun, his illustrated memoir of the war in Syria.