The secret government training exercise started off as planned: Dozens of special agents transporting dangerous nuclear cargo by truck responded to a simulated attack.

Then the coughing began.

After wading neck-deep through a creek in pursuit of the mock attackers, Tim Lamey suddenly got dizzy and started coughing so hard he could barely breathe.

Another agent, Farmer Roberts, ran through the creek in a different location. “I had to stop. I started coughing, really I mean uncontrollably. You know, it was very obvious to me that something wasn’t right,” he told BuzzFeed News.

Nearby, Anthony Gunter crossed a dried-up creek bed and fell into the dust. “It took my breath,” he said. “My lungs got full. My eyes were full.”

The Southern Cross Exercise, held at a South Carolina nuclear facility owned by the Department of Energy, would see at least 28 people report symptoms that included coughing, difficulty breathing, dizziness, headaches, sneezing, nosebleeds, rashes, and vomiting. They fell ill in April 1991, mostly along the Meyers Branch creek stretch of the heavily polluted Savannah River Site. Larger than the five boroughs of New York City, this vast federal facility contains production and processing plants for tritium and plutonium 239, highly radioactive components for nuclear weapons. It was then, and still is, a Superfund site.

The sudden and mysterious illnesses that arose during those fateful training exercises have never before been reported. Neither has the decadeslong search for the truth of what caused the wave of sickness, led by the individuals who fell ill, not the government that was supposed to protect them. As the US launches into a new Cold War complete with Russia brandishing nuclear weapons, this case is a stark reminder of the risks faced by the multitudes of people needed to maintain such a dangerous arsenal.

The Department of Energy did not respond to detailed questions and criticisms about how it handled the incident. But in response to BuzzFeed News’ investigation, the agency said it would launch a search for related records and pledged to make those records available to former staff.

“Despite the reviews that have already been conducted, I have directed all appropriate NNSA offices to search for records related to the Southern Cross exercise for review, and to make those records available to interested former Department of Energy employees,” Under Secretary for Nuclear Security and Administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration Jill Hruby told BuzzFeed News in an email. “Given the passage of time, it may not be possible to get answers to all the new questions these former agents have now raised. But the difficult work that they and all federal agents past and present have done for our nation is valued and critical to NNSA’s national security mission. Given their service, it is important that we try to respond to their concerns.”

Most of the men who got sick were part of an elite and secret group of nuclear couriers, armed government agents employed by the Department of Energy and tasked with safely transporting the nation’s most powerful weapons. But when these public servants got sick on the job at a contaminated site, they couldn’t even get basic questions answered about their health. Eventually, they threatened a lawsuit. Even Bill Richardson, then a cabinet secretary and the highest-ranking official at the agency, got involved.

Yet interviews with 15 people involved in the case and thousands of internal, legal, and scientific documents reveal that the US government first failed to take basic precautions to protect its workers who participated in the exercise, then repeatedly sidelined, dismissed, and undermined their concerns.

When the exercise participants “tried to seek help from their government — which would also be our government — it was more than a cold shoulder,” said Duff Westbrook, who used to serve as the lawyer for the exercise participants. It was, he said, “a very aggressive pushback.”

“We’re just a bunch of couriers trying to find an answer to why we got sick and how to prevent it from happening again and to get a truthful answer from the administration.”

Over the years, government officials did take some steps to find out what happened. They looked into whether the vegetation in the area could have caused such a reaction; whether any pesticide had been applied there; whether methane or hydrogen sulfide was in the air; whether the agents ate or drank something off; or whether grenade smoke was to blame.

But what’s still maddeningly unclear, decades later, is whether officials looked into the possibilities that the exercise participants were most concerned about and that seem most obvious given that the exercise happened a few miles downstream from the site’s nuclear facilities: Was the soil or water contaminated with any radiation or toxic pollutants? The government’s own documents give conflicting answers.

Now that the nuclear couriers are long retired and no longer have their jobs on the line, 11 of them are finally speaking out. At least five of them say they’ve continued to suffer health effects, from chronic fatigue to sinus problems to decreased lung function to cancer, that they believe might be related to the incident 30 years ago.

“We’re just a bunch of couriers trying to find an answer to why we got sick and how to prevent it from happening again and to get a truthful answer from the administration,” said Lamey, who retired from government in 2012 and has since suffered from prostate cancer and a recurring skin cancer.

Ever since the Energy Department’s Transportation Safeguards Division launched in 1975, when the US was mass producing nuclear weapons in the middle of the Cold War, its nuclear courier program has been shrouded in secrecy.

The reason, of course, is national security.

If a convoy of couriers were transporting, say, a nuclear missile by truck on the highway, others on the road would have no clue. The armored truck trailers have few markings, the escort vans are discreetly spread out in front and far behind it, and the couriers driving the vehicles dress like normal truck drivers.

But confusing couriers with truck drivers would be a mistake. Mostly men who often served in the military, law enforcement, or both, couriers are trained to defend their cargo against an attack and must meet strict annual fitness requirements. “Essentially what they were,” Westbrook explained, “was a group of Rambos who drove around trucks with nuclear weapons in them.”

“A group of Rambos who drove around trucks with nuclear weapons in them.”

In any given year, there are a couple hundred nuclear couriers. Each group, known as a section, usually holds its own tactical training exercises at least once a year to run through possible attack situations, sometimes in collaboration with other military, security, or law enforcement forces. That was the purpose of the Southern Cross Exercise.

The plan was for the couriers from the Oak Ridge section in Tennessee to participate in a series of scenarios at the Savannah River Site starting on April 21, 1991. This would be a massive training involving hundreds of people, including members of the Georgia and South Carolina State Police as well as staff from several government contractors.

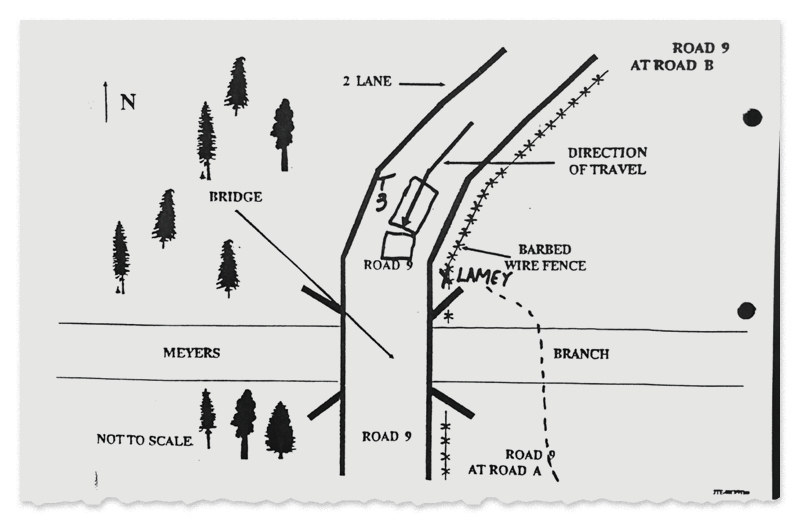

The health problems began with Scenario 5, which commenced at 4:14 p.m. on April 24. A convoy consisting of roughly 30 nuclear couriers spread across multiple vehicles hauling special nuclear material was mock-attacked by at least eight guards from Martin Marietta Energy Systems Corporation along Road 9 near Meyers Branch creek in the southern section of the Savannah River Site. The objective of the “war game,” as some of the former couriers called it, was simple: Eliminate the threat. The couriers did so in four hours. The simulation seemed to be a success.

Then the reports of participants experiencing breathing difficulties during and after the exercise started coming in.

For Lamey, the problems started mid-exercise, as soon as he crossed a narrow creek in pursuit of some of the attackers. “When I came out on the other side, I experienced dizziness, difficulty breathing, and coughing,” he later described in sworn testimony provided to the Department of Energy’s Office of Inspector General. “I did not taste or smell anything extraordinary, but the creek did have the appearance and smell of a sewer.”

Lamey, who had served as a nuclear courier for nearly five years at that point, decided not to immediately flag his health problems by radio, which carried the risk of ending the exercise early. Nor did anyone else. But as soon as the exercise was over, Lamey, who was still experiencing shortness of breath, told a training instructor what was happening and was directed to get dry clothes from a nearby guard post.

According to Lamey, the captain on duty at the guard post told him that “the water and streams at [the Savannah River Site] were ‘hot,’ which I interpreted to mean contaminated or radioactive, and suggested that I immediately go to Health Protection to get a dosimeter reading” to measure possible radiation exposure. Lamey said the captain also avoided coming close to him, throwing him dry overalls from a distance.

While on duty, the couriers usually wore around matchbox-sized dosimeter badges clipped to their clothing that monitored exposure to radiation. The badges did not provide real-time monitoring but were checked every quarter for radiation exposure. The assumption was the courier’s potential exposure, if any, was very low. While there were many limitations to the badges — they only picked up certain types of radiation, for example — they were better than nothing. But for the training exercise, the government had not provided them to the couriers.

After the exercise, Thomas McIntyre had also complained of symptoms. “I had mucus running from my nose to the ground and was coughing uncontrollably to the point that I nearly threw up,” wrote McIntyre in notes he’d taken within a year of the incident to share with medical experts. He said he initially told his section chief that he needed medical attention, only to have his concerns dismissed as “allergies.” After finding out another colleague was sick, he said, they sought help from a safety official involved with the exercise who took them to a nurse at the nuclear site.

Their visit to the nurse was documented in a government memo titled “Respiratory Difficulties,” dated April 25, 1991 at 4:09 a.m. The nurse “did not indicate any abnormal physical conditions,” the memo stated, but her check was limited to listening to the chest and checking the couriers’ blood pressure. Soon after, eight other exercise participants requested a similar medical review, but because of a bureaucratic error, they were not allowed to be treated by the medical professionals there, according to official reports.

Even more cases were reported the next morning. One of those people was Gunter, who had gone to bed hoping his itchy eyes and runny nose would go away. “The next morning, when I got up, my eyes were swollen shut,” he said, “just barely little slits that I could see out of.”

He received permission to sit out the next exercise and was taken to see a doctor at the Savannah River Site. Gunter was one of only a handful of the people who got sick and received medical attention in the days after the exercise, documents and interviews reveal.

“It wasn’t much of an examination,” he said, and recalled being told his symptoms were an allergic reaction. At the time, Gunter had no known allergies.

By April 26, Lamey, McIntyre, Gunter, and the other Scenario 5 participants were directed to fill out a 10-question survey asking about their symptoms and when they occurred. The responses suggested most of the people who got sick were near Meyers Branch creek, which was located a few miles downstream of a facility called the P-Reactor that used to produce tritium and plutonium.

Lamey’s lungs were slow to recover. Two months after the exercise, a physical exam by the doctor at work showed that his “lung capacity had been reduced compared to previous examinations,” according to his sworn testimony.

Lamey used to be an undercover cop, and he said that in one case he had to testify about events that had happened a decade earlier — something he was able to do only because he kept good notes. He leaned on that habit again, taking notes and collecting documents as he repeatedly pressed his supervisors for medical testing and status updates on various internal investigations into the incident, and he submitted a public records request for all documentation tied to his possible exposure.

Lamey concluded that there was a government “cover-up,” and shared thousands of pages of personal, internal, public, and legal records on the incident with BuzzFeed News.

The documents, combined with interviews, do not prove a cover-up. But they do show that the government’s response was haphazard and flawed. The government brought in a rotating cast of people to investigate what happened, and glaring possible explanations for what happened were never fully explored.

In the days and weeks after the exercise, contractors and government officials began looking into what happened, and one contractor even reached out to the CDC — but despite interest from the CDC, investigators never followed up.

By May 1991, officials were stumped but offered two tentative theories for what had happened: “unspecified allergic reaction to decaying pollen and vegetation” or “exposure to grenade smoke that had settled in concentrated pockets in low lying areas,” according to an internal report summarizing the preliminary investigation.

But by the investigators’ own admission, the grenade smoke theory couldn’t be a complete answer because “not all personnel who reported symptoms were exposed to the smoke.” Officials also weren’t fully convinced by the allergic reaction idea. The most they would say is that they couldn’t rule it out.

Seven months after the exercise, a top official from the couriers’ Transportation Safeguards Division, or TSD, was already saying it probably was too late to find out definitively what had happened, even while ordering further investigation. Published in February 1992, the resulting report was put together by health official David Anglen and indeed offered no explanation for the illnesses, although it dismissed many possibilities. Anglen declined to comment on the investigation.

Officials reported how they brought in a botanist from the Savannah River Ecology Laboratory to review the vegetation at the exercise location for plants that could make people sick (none were found). They also checked whether any herbicides were recently applied (none were), checked an unlabelled 55-gallon drum for contamination (none was found), looked for discolored or dead plants as a sign of chemical contamination (none were found), and sampled the air at the exercise site for hydrogen sulfide and methane (neither was found).

Perhaps more important than detailing what TSD had done so far, Anglen’s evaluation showed what officials had not done before and after the exercise: They had not checked the water or soil for radiation, heavy metals, or other pollutants.

TSD safety personnel spent very little time — less than one hour — checking the site of the exercise before it took place. In response to a courier raising concerns about the rivers being polluted, Anglen’s report concluded: “This potential hazard was not adequately addressed prior to the exercise.”

The report also detailed how a Savannah River Site official informed TSD that “there were ‘numerous’ radiation areas” at the nuclear facility site, yet the exercise site had not been checked ahead of time for possible radiation.

The report also mentioned how “at least four months after the exercise, some participants still are reporting experiencing respiratory symptoms that they believe are related to the exercise.” Martin Marietta had already implemented a medical review for their guards by this point, according to the report, and TSD planned to follow their lead.

Lamey and other couriers said this didn’t happen.

No blood or urine samples were taken, nor were tests for radiation or chemical exposure ordered for the people who reported symptoms in the hours, days, or weeks after the incident.

A month after the training, Lamey wrote the program director, Randolph Sabre, asking “to have a complete physical and full body count conducted, due to the fact that I am still coughing up some type of fluid.” Lamey noted how 30 days had passed and “DOE has not made any efforts to check any personnel that was apparently exposed.”

By the end of 1991, McIntyre was also asking for testing. Both Lamey and McIntyre were finally tested for radiation exposure in early 1992, almost a year after the exercise, through what’s called a full body count, which involves using a machine to scan for radioactive material in the body, and a special urine test.

According to McIntyre, his results came back normal, and he recalled being told by the officials conducting the tests that “after all of this time it would be unlikely that the tests would find anything significant.”

Lamey was also told that everything was normal on the full body count. His urinalysis was a different story: Trace levels of tritium were found. “[S]ince tritium has an effective half-life in the body of only ten days,” he recalled being told, “it is highly unlikely that this result is related to the exercise in which this individual was involved on 4/24/91.”

Meanwhile, the nine other couriers involved in the exercise who spoke to BuzzFeed News said they hadn’t been tested at all.

By 1994, Lamey and at least 34 other exercise participants and observers, a mix of couriers and Martin Marietta guards, had lawyered up and were flirting with the idea of suing the agency for damages. (Government records indicate at least 28 participants fell ill, but seven others joined the suit.) To have any chance at success, they needed documentation about the investigations into the exercise and the Savannah River Site’s environmental history.

Earnest Sanchez, an Essex official who had been taken off the investigation, tipped Lamey off to the existence of a June 1990 document called the Tiger Team Assessment of the Savannah River Site, which detailed widespread environmental damage there. When asking his superiors at TSD for a copy went nowhere, Lamey eventually got the report by submitting a records request directly to the Savannah River Site.

Put together by the Department of Energy, the assessment exhaustively detailed how the site was “not in compliance” with many of the department’s safety and health standards.

“What the hell were you people thinking? Seriously.”

Moreover, the assessment listed “deficiencies” in waste management, “inadequate monitoring of radiological releases,” “unresolved fish kill issues,” a “failure” to meet South Carolina water pollution rules, and a concern that drinking water systems were “not adequately inspected and protected from potential contamination sources or unauthorized access,” among other problems. The report did not specifically mention Meyers Branch creek, where many of the exercise participants reported falling ill.

The Environmental Protection Agency put the Savannah River Site on its National Priorities List of toxic waste sites, or Superfund sites, in 1989. Just in the past decade, from 2011 to 2021, the federal government spent more than $14 billion on the site’s environmental cleanup, and has proposed spending $1.5 billion in 2022. According to the agency’s latest estimates, the cleanup will not be finished until 2065.

The fact that the Department of Energy had its guys “go play a war game at a Superfund site that has a long, long history of heavy metals in the soil, the water table, and everything else, I just shake my head,” said former courier Jim Bailey, who had trouble breathing and got a rash during the Scenario 5 exercise. “What the hell were you people thinking? Seriously.”

In 1997, the group commissioned independent toxicology tests of their pubic hair. According to the handful of results reviewed by BuzzFeed News, some of the men had high levels of toxic heavy metals such as aluminum, antimony, lead, and mercury. This wasn’t hard proof the men had been contaminated. But for at least four people, including McIntyre, it led to the government paying for additional testing in 1998 of their blood, urine, and chest function. The results were inconclusive.

Also in 1998, the agency brought in a team of outside experts to review a range of troubles with the courier program, including the Savannah River incident, relying exclusively on interviews and documentation provided by the agency.

Their report raised more questions. The outside experts did not think radiation was to blame, but they found it “likely that some unusual physical event took place to cause the symptoms.”

Their report also said that “no significant radiation, toxic chemical, or heavy metal contamination was noted” despite the collection of “extensive” water and soil samples. But when the couriers later asked for the data underlying this report, no information on any sampling was provided, and in thousands of pages of documents reviewed by BuzzFeed News, there is no mention of samples being collected — except one, which says the opposite. In a 1992 letter to Lamey, the Energy Department stated that water or soil samples had not been taken.

Near the end of their report, the outside experts excoriated the DOE: “A mediated settlement of the issue and claims at a much earlier time would have been preferable by far to the contentious stand-off of the past eight years. It is unlikely that the actual cause will ever be known with certainty, but it is essential that the afflicted special agents” — the nuclear couriers — “become convinced that their concerns have been recognized, and that a fair and equitable resolution has been researched. Continued lingering of the negative feelings and antagonism of the past is very harmful to the personal well-being of the affected agents, as well as to operational effectiveness and unit performance and stability.”

The report ultimately recommended a “Mediated legal close out of this incident,” which did not happen. This came as a shock to one of the outside experts, Linda Kaboolian. “I am heartbroken about this,” she said, “because what happened to those guys at Savannah River was a screw-up.”

Within months of the final report’s release, the couriers, through their lawyer Westbrook, directly appealed to Bill Richardson, then energy secretary, for help.

“The 35 couriers who were injured during the Southern Cross Exercise have tried for over seven years to resolve their concerns within DOE,” Westbrook wrote. “The publication of the Review Panel’s report gave them renewed hope that they would finally be afforded relief,” but official refusal to acknowledge responsibility “has proven these hopes to be false. These individuals are now asking you to help them.”

On Richardson’s behalf, then–assistant secretary of Defense Programs Vic Reis and General Counsel Mary Anne Sullivan agreed to meet with Westbrook. It didn’t go well. “Their attitude was: you don't matter, and your clients don’t matter either, and we’re not going to help you in any shape or form,” said Westbrook. Sullivan, he added, claimed the agency was unaware of any health issues beyond “some guys coughed.” In an email to BuzzFeed News, Sullivan said she didn’t remember the meeting but that what Westbrooks remembers “does not sound like the kind of response I would have offered.”

Westbrook left the meeting appalled, he said, because some of his clients suffered from lichen planus, a skin condition that can be associated with heavy metals exposure, and others from persistent breathing problems. And in one case, courier Jim Bailey’s firstborn daughter suffered from three rare tumors in the brain and died after only four months.

There was never any settlement. Instead, the agency agreed to bring in Dr. Lee Wugofski, a medical occupational specialist, to do a final review of what happened.

In May 2002, the agency held a private briefing for certain current and former staff about Wugofski’s conclusions. According to Lamey, who attended, the agency determined that the couriers were exposed to something but it still did not know what. Neither he nor the other attendees were given anything in writing about the results of Wugofski’s review.

In an interview with BuzzFeed News, Wugofski, sitting in the cafeteria at his San Francisco office, said the couriers came into contact with something but, “We don’t know what it was.” He added, “From what I had, I couldn’t make any connection. I didn’t see any smoking guns.”

For the review, Wugofski said he did not examine or speak to the people involved in the exercise — he could only review the agency’s records. Even with this limited assessment, he did not think the symptoms reported at the time, or the health conditions reported later, were consistent with radiation exposure. “When we worry about things like radiation,” he said, “you’d expect to see more than I saw in the charts years later.”

When asked for a copy of his report, Wugofski said to ask the Department of Energy. BuzzFeed News is pursuing a Freedom of Information Act request for a copy of Wugofski’s report and presentation.

For Tim Lamey, the mystery of the Savannah River exercise has continued to plague him. He spent an additional two decades with the courier program, before retiring in 2012. His retirement has been filled with one cancer diagnosis after another. Skin cancer in 2010. Prostate cancer in 2o11. Skin cancer again in 2017, in 2019, and in 2020. Lamey is not the only former courier to get sick with cancer — dozens and dozens have — but he’s one of the few that has tried to get government compensation for it.

If federal health experts determine that an Energy Department employee’s cancer is more likely than not caused by the person’s nuclear work, they can get a lump sum of up to $150,000 and support with medical bills.

Lamey has applied five times; all ended in rejection. In his appeals, Lamey always brings up the Southern Cross Exercise and how he was exposed to something, even though he can’t say what. He believes that having official documentation from the Department of Energy as to what happened at the Savannah River Site would help his case, or those of others who got sick there.

Wugofski said he was told that a copy of his report was going to be added to each affected employee’s personal file. But in Lamey’s case, he said, that never happened.

In recent years, the number of former couriers who have gotten sick or died from cancer has continued to tick up. Roberts got prostate cancer in 2019. Bailey got skin cancer in 2015. Determining the cause of cancer is notoriously difficult, but among the surviving couriers, there’s a growing consensus that their cancers aren’t normal. So Lamey and some others have decided to finally go public about their decades-old concerns, and that includes the mystery of the Savannah River incident. “What,” Lamey asked, “do we have to lose?” ●

BuzzFeed News reporter Emily Baker-White contributed to this story.