The journalists at BuzzFeed News are proud to bring you trustworthy and relevant reporting about the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Outbreak Today.

Last week, the Department of Homeland Security revealed preliminary research results with seemingly optimistic news for the summer: In agency lab tests, the coronavirus died faster in sunnier, hotter, and more humid conditions.

The new analysis, which has not yet been released in full or peer-reviewed, was the basis for President Donald Trump’s bizarre suggestion to bring “light inside the body” as a way to treat an infection. But the new findings are also consistent with a growing number of lab experiments and models that suggest a link between virus viability and “seasonality,” or weather and climate conditions.

So does this mean the US should expect the pandemic to end this summer?

It’s become a popular idea, fueled in part by Trump’s claims that the virus would “disappear” in the warmer months "like a miracle." According to the results of a new Pew Research Center survey, 22% of about 10,000 US adults polled in April said they’d heard the virus would go away in warmer weather.

But scientists are warning that’s unlikely to happen. “Don’t expect miracles,” said Roger Shapiro, an associate professor of immunology and infectious diseases at Harvard University.

While the links to seasonality are promising, Shapiro and other scientists stress that the disease has already spread worldwide regardless of warm weather and that much of the population is still vulnerable to infection.

“I’m hopeful weather and climate variables reduce transmission of this pathogen,” said Jesse Bell, a climate health expert at the University of Nebraska who is studying this issue. But he added: “I wouldn’t stake any money on it.”

Here’s what we know so far about the impacts of seasonality on the coronavirus spread:

1. Yes, the virus does seem to die faster in sunnier, hotter, and more humid lab conditions.

A handful of lab experiments in China and the United States suggest the coronavirus decays more quickly in summer versus winter conditions.

Researchers in Hong Kong found that when a sample of the coronavirus in a cell culture was left at 39 degrees Fahrenheit, it was still detectable after 14 days; at 71 degrees, the virus degraded significantly over 7 days and was not detectable after 14 days. And when exposed to 98 degrees, no virus was detectable by the second day, according to results published April 2 in the Lancet.

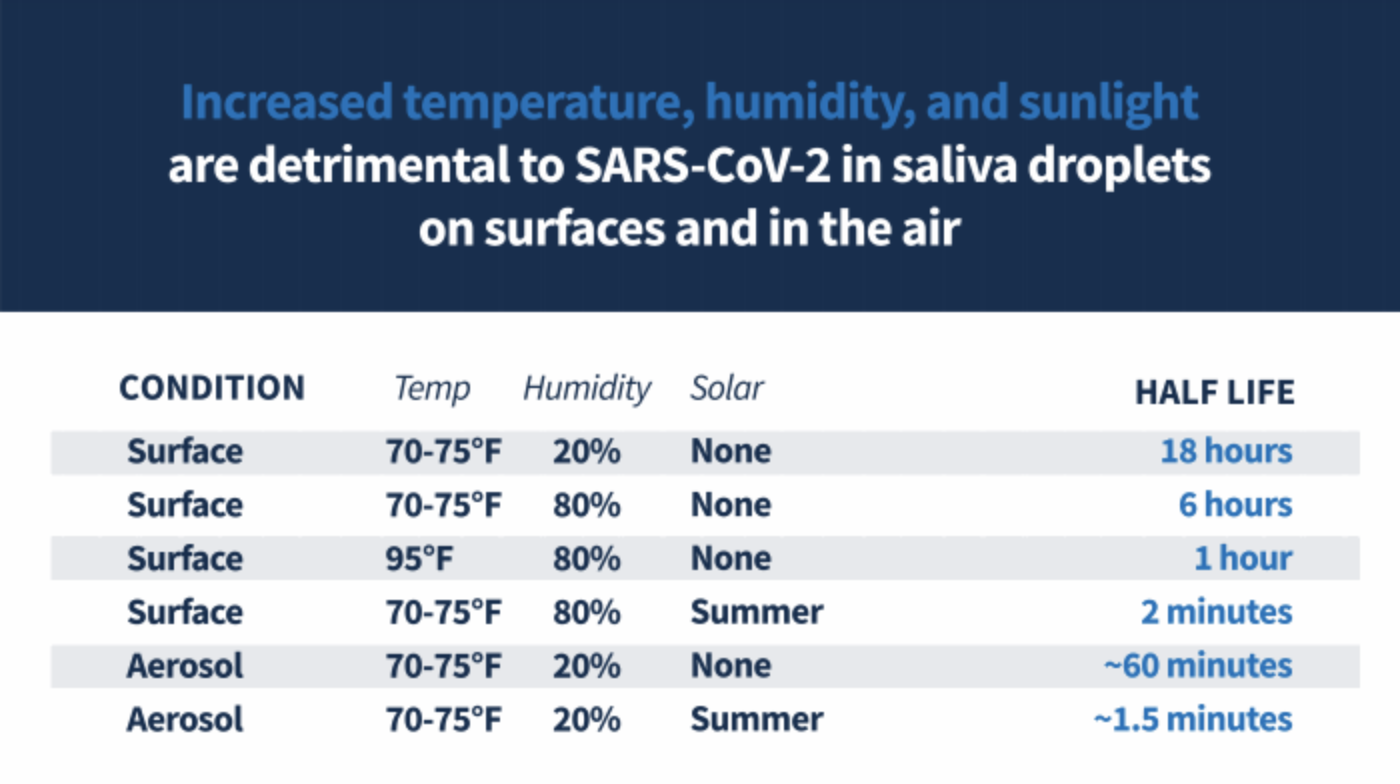

The preliminary DHS study announced similar findings — though the agency did not release its methodology or raw data. The experiment exposed virus in droplets of simulated saliva on a stainless steel surface to different levels of solar radiation to simulate sunlight, as well as a range of temperatures and humidities.

Under the 70 to 75 degree Fahrenheit temperature range, with 20% humidity, the virus decayed by half over 18 hours; when humidity was increased to 80%, the virus decayed by half in only 6 hours. When the temperature was increased to 95 degrees Farhenheit combined with the higher humidity, the virus half-life again dropped to 1 hour. And the virus rapidly decayed in 2 minutes when exposed to 75 degrees Fahrenheit, 80% humidity, and intense solar radiation used to simulate sunlight.

The virus similarly disappeared rapidly in aerosol form, decaying by half in about 1 hour and 1.5 minutes, respectively, when exposed to 70 to 75 degrees Fahrenheit temperatures, 20% humidity, and no versus intense sunlight.

“Our most striking observation to date is the powerful effect that solar light appears to have on killing the virus both on surfaces and in the air,” William Bryan, senior official performing the duties of the DHS undersecretary for science and technology, said in a statement shared with BuzzFeed News. “We’ve seen a similar effect with both temperature and humidity as well, where increasing temperature, humidity, or both is generally less favorable to the virus.”

A separate study by the University of Nebraska Medical Center developed a method to decontaminate N95 respirators, protective masks used by health care workers treating COVID-19 patients, using ultraviolet (UV) light.

With each of these studies, it’s important to remember that how the virus behaves in the lab may not match its behavior in the real world, according to David Relman, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Stanford University who contributed to a National Academies of Sciences report on the coronavirus’s survival in hot and humid conditions shared with the White House. He added that these experiments also do not account for human behavior, such as whether people keep up social distancing, wearing masks, and washing their hands.

2. Other studies have noted that the virus has spread more slowly in hot and humid countries — but even those countries are not immune.

Not every country is seeing the virus spread at the same clip as the United States, where more than 1 million are confirmed to be infected. Though this has been in part driven by a slow response to containing and responding to US outbreaks, as well as a botched rollout of testing for the disease by US officials, another contributing factor may be weather and climate.

An MIT study that analyzed virus spread and so-called seasonality conditions across the globe found 90% of virus transmission recorded through March 22 occurred within the temperature zone of 37 to 62 degrees Fahrenheit.

Updated research on the topic, which has not yet been published, came to the same general conclusion that temperature and humidity are impacting transmission, Qasim Bukhari, one of the study's authors, told BuzzFeed News.

He noted that while low reported case numbers in certain places may be attributed to a lack of access to testing or a variation in social distancing measures, these things do not fully explain lower case numbers in hotter and more humid regions globally.

Ongoing research out of the University of Nebraska suggests a similar trend. “There is some kind of underlying climate and weather factor that is influencing the spread of this disease,” said Bell. His team’s research showed the strongest relationship between the length of day and ultraviolet light, which usually peaks in the middle of the day and during summer. “These variables did seem to decrease transmission.”

Perhaps the biggest piece of evidence the coronavirus pandemic won’t soon disappear with the change of seasons is the fact that even the hottest and most humid countries haven’t been immune to the pandemic.

“You’re still seeing it spread all across the globe,” Bell said about the disease.

3. The US outbreak may slow down in the summer, but the virus is too infectious to disappear from heat alone.

When it comes to sunnier and warmer weather, “the effect could turn out to be very small,” said Relman of Stanford. “It may not even be noticeable.” Here’s why: The virus is very infectious, and there are a lot of people that haven’t yet been infected.

There are also still big questions about how this virus is transmitted: What is the viral load it takes for someone to get infected? What size particle is most infectious?

If it takes a lot of virus to get someone infected, Relman explained, then perhaps the combined impacts of sunlight, humidity, and temperature on the virus’s survivability can greatly cut down transmission. But if it only takes a little bit of virus, especially small particles of the virus that can stay aloft in the air for hours, you’ll still see transmission inside the offices, restaurants, and movie theaters people will be spending time in, regardless of the weather outside.

Harvard’s Shapiro agreed. “It might go down a little because we know that the virus does not like hotter and wetter conditions,” he said, but it’s unlikely to stop the pandemic because “we just have too many susceptible people.”

Though the flu is a completely different type of virus, it also has a seasonal pattern, peaking in the colder US month — from October to May. But past flu pandemics also suggest the influence of seasonality will be minimal. “There have been 10 influenza pandemics in the past 250-plus years — two started in the northern hemisphere winter, three in the spring, two in the summer and three in the fall. All had a peak second wave approximately six months after emergence of the virus in the human population, regardless of when the initial introduction occurred,” according to the NAS report.

All the experts agreed that seasonality is only part of the picture, and stopping the spread of the virus will continue to rely heavily on changed behaviors.

“Weather and climate can only explain part of the transmission, the other factors are nonenvironmental — social distancing, washing hands, covering your cough, staying home when you are sick — and these factors are probably the most important in a pandemic,” said Bell of the University of Nebraska. “Understanding climate and weather will only tell you when the environmental conditions are optimal for the spread of the virus.”