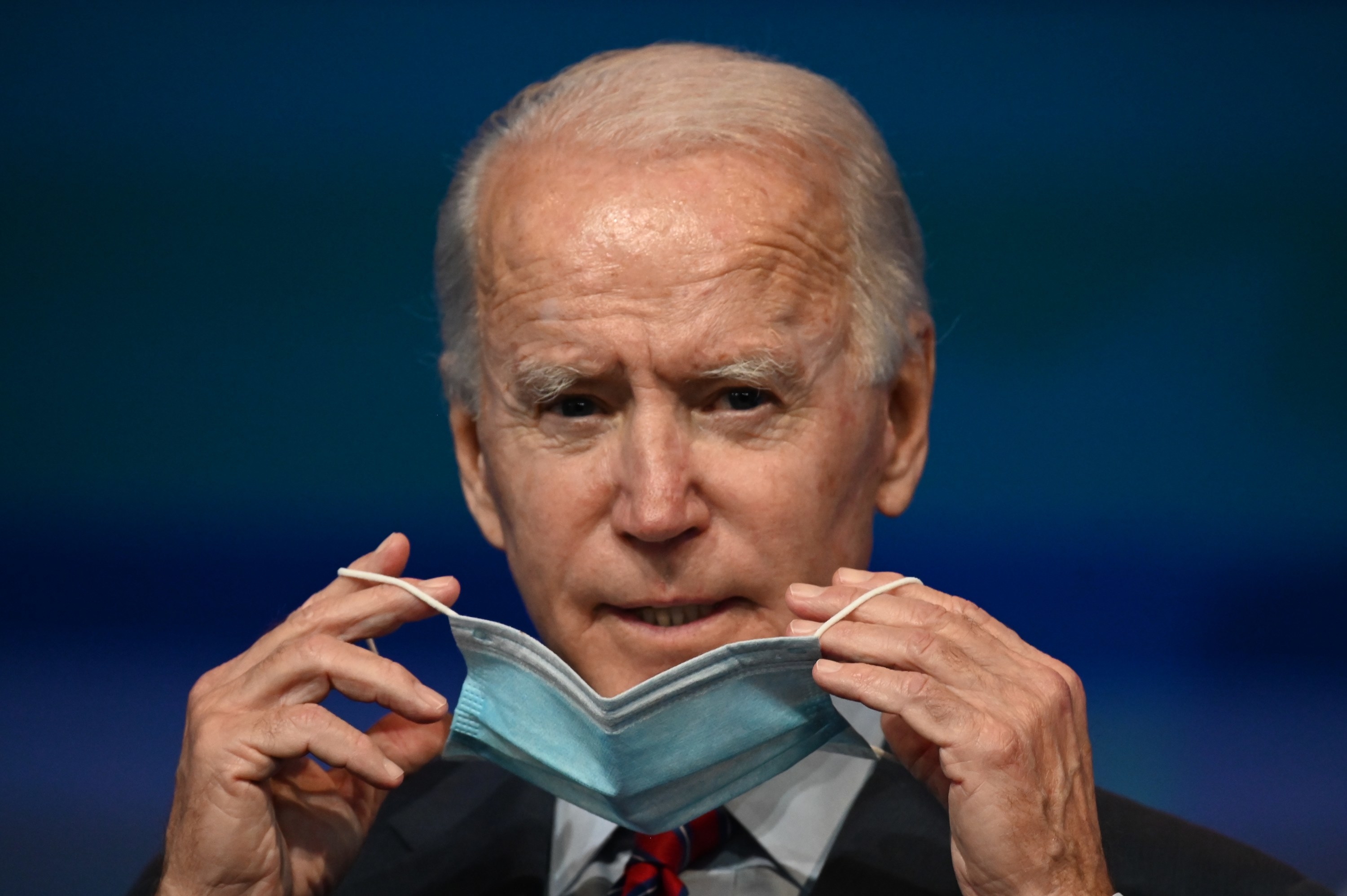

With two coronavirus vaccines available, President-elect Joe Biden’s biggest challenge in ending the deadly pandemic will be to convince Americans to take them.

The logistics of distributing the multiple vaccines, securing enough doses for everyone, and maintaining other basic precautions until then — like social distancing and mask-wearing — are hard enough. But even if all of that goes smoothly, there's a deeper issue that Biden and his new administration will have to contend with: President Donald Trump's toxic legacy of routinely politicizing and downplaying the deadly disease, which has emboldened anti-vaxxers against a backdrop of rampant misinformation in the months leading up to the vaccine rollouts.

Biden, unlike Trump, has committed to following the science to overcome the pandemic. But it’s not clear what his administration will do about misinformation. Biden’s transition team has declined BuzzFeed News’ requests to speak with soon-to-be White House chief of staff Ron Klain, who headed up the Ebola crisis response during the Obama administration, or others who could address how they will tackle this crisis. T.J. Ducklo, a Biden spokesperson, instead offered a short statement and promised details “in the coming weeks.”

“The president-elect has made clear that rebuilding the trust of the American people is a priority, which he'll do by providing accurate, fact-based information about progress in getting the pandemic under control, distributing vaccines, and ensuring testing capacity,” said Ducklo in an emailed statement. Besides preparing to lead the vaccine distribution process, he added, “we are also planning on how to communicate in the most creative, transparent and effective ways to reach Americans where they are."

But eight experts on the coronavirus, climate change, risk communication, and disinformation told BuzzFeed News that while prioritizing science is a critical first step in tackling the problem, it is not enough.

“Following the science is necessary but not sufficient,” said Matthew Seeger, a risk communication expert at Wayne State University who worked at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for more than a decade.

According to Dominique Brossard, a science and risk communication expert at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, that is because, “Humans do not make decisions based on facts. Facts alone do not change our mind.”

And a lesson learned from studying another, perhaps even bigger crisis — climate change — is that it’s not enough for scientists or the government to understand the problem and possible solutions; you need the public involved as well, said Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. “This isn’t an ‘all of science’ communication or [an] ‘all of government’ communication,” he said, “this needs to be an ‘all of society’ communication.”

So if you want to convince people to get inoculations, having public health officials simply stress the vaccines’ safety and efficacy won’t be enough. “We need to demonstrate that people are willing to take the vaccine,” Seeger said, “because once you know your neighbor, your friend, the person you went to high school” are all getting it, “that will create a snowball effect, and more people will be willing to take it.”

Biden was vaccinated in front of TV cameras Monday. Vice President Mike Pence received his vaccination Friday. Trump, who was briefly hospitalized with COVID-19 in October, has not committed to taking the vaccine, publicly or otherwise.

Democrats in Congress are also urging Biden to place a greater emphasis on fighting misinformation, sending two separate letters to the president-elect on the issue this month. One called for a multiagency task force to provide “guidance for how best to proactively monitor for disinformation and communicate during a disinformation or misinformation event.”

“During COVID, we've seen that there has not been clear and concise messaging from the federal government, that they have not been able to really monitor and do anything with disinformation spread,” Rep. Jennifer Wexton, who heads the Congressional Task Force on Digital Citizenship, told BuzzFeed News. “If we have a task force that works across agencies, they'll be much better equipped to be able to do those things.”

The other letter urged the Biden transition team to add a misinformation expert to its COVID-19 task force, singling out Joan Donovan, the research director of Harvard University's Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, as a strong candidate.

Donovan herself agrees on the need for the position, even if it's not presently a reality. She and her team have been studying disinformation surrounding the virus since it first broke out, and recognizes it won't be an easy issue to solve.

"I think part of the role has to address public health messaging with an understanding that this is a different problem than public health has dealt with in the past," she said in a phone call with BuzzFeed News. "I'm not talking about local rumors. I'm not talking about small-scale hoaxes and grift. I'm talking more about how the design of social media itself allows very small claims to reach millions of people."

The problem has broad implications for both the pandemic and for democracy, Donovan said, and such a position could serve as a blueprint for other issues that disinformation touches. But she worried about the job being politicized.

"It does put that person in the crosshairs of those that are calling any kind of content moderation censorship," she said. "Those that believe social media companies shouldn't moderate any content, who consider misinformation a natural part of online conversation and therefore don't want anything done to stop this problem from perpetuating itself."

A coalition of 47 nonprofit organizations also urged the Biden–Harris administration to embrace the “unique opportunity to begin repairing our broken information ecosystem” in an open letter sent on Monday and first reported by Axios. The top recommendation is including a disinformation expert on the COVID task force.

“There is no panacea for the information crisis — no simple bill or regulation that will alone cure its noxious society-wide impacts,” said the letter, which was signed by Accountable Tech, Greenpeace, the Center for American Progress, and others. “We must instead fight it with government-wide strategies.”

From the start of this pandemic, the Trump administration took steps that flew in the face of every recommendation that experts said was needed in a public health crisis. Instead of normalizing protective measures like wearing a mask, Trump flouted and even mocked them; he contradicted, demeaned, and silenced his own public health experts; he politicized the government’s response; he was not transparent about the crisis, downplaying its severity; and he amplified misinformation. His administration only last week began rolling out a long-awaited $250 million public information campaign on vaccines.

Meanwhile, the virus’s toll has ballooned. More than 300,000 people have died in the US, and hospitals across the country are at capacity.

Despite the worsening situation, the number of people who said they would take a vaccine is far lower than public health experts say is needed. According to an Axios/Ipsos poll conducted this month, 53% of respondents said they’d likely get a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it’s available, up from 38% in October. Even more people — 69% — said they’d get the shots if the vaccine had been proven to be safe and effective by public health officials. Those numbers are still short of what experts would hope for.

“I have seen this movie before,” Sen. Amy Klobuchar, who cosigned one of the two letters urging Biden to appoint a misinformation specialist to his task force, told BuzzFeed News in a telephone interview last week. “In Minnesota, we have anti-vax groups, including those that have influenced some of the members of the Somali community. We've had outbreaks of measles in our state over the last decade.”

Klobuchar, who competed against Biden for the Democratic presidential nomination this year and quickly endorsed him after dropping out, said she had not yet seen a response to the letters from the president-elect or his transition team. But, she added, she’s confident that he was taking the recommendations seriously.

“We’re not concerned about it, only because we know that Joe Biden is devoted to getting out the facts, and that was what his campaign was defined by the moment he wore a mask out onstage,” the Minnesota senator said.

She added that the Biden administration would have to work with governors and mayors to combat misinformation and advance an aggressive marketing and communications plan.

“It’s not one-size-fits-all, so a lot of this will be targeted,” she said, suggesting public service announcements, social media campaigns, and yard signs.

“People speak about herd immunity,” Klobuchar said. “Well, we’re going to need herd reality here. The more people who hear that it's going to be OK, it becomes contagious.”

Experts on crisis and science communication offered another suggestion: Bring members from across the political spectrum into the same pro-vaccine messaging campaign. That means involving community organizations on the ground, especially among groups that have a heightened vaccine reluctance. One of the letters to the transition singles out hesitancy among Black and Latinx Americans, as well as women, who respectively have legitimate reasons for distrusting the healthcare system.

Sandra Crouse Quinn, a professor at the University of Maryland who studies health equity, said, “Disinformation and misinformation at present is echoing what's already there and amplifying what's already there.”

Donovan said Biden’s approach will need to go beyond addressing gaps in knowledge and putting out accurate information for people to find — because inaccurate information travels faster online, and it’s often more shareable.

“I think this position, whoever it is, has to call attention to both the supply side and the demand side for misinformation and crank up the volume on timely, local, relevant, and accurate information, while also figuring out how to dial down misinformation at scale,” she said. “That requires a strong advocate for the truth [who also] understands how social media constitutes a part of the problem.”

Seeger of Wayne State University agrees. “Rumors, misinformation, [and] distortions occur primarily when there is an absence of credible information, and that’s what has happened in this particular circumstance. There has been insufficient credible and consistent messaging, and that has allowed some of these other messages to emerge,” he said. “We need to make sure we sort of flood the zone with accurate messages when those inaccurate messages are out there.”

Some federal agencies have made attempts at controlling rumors in the past but get bogged down in the distribution, Donovan said. Leveraging both social media and on-the-ground community leaders is key for her and for other experts who have studied the field.

“For every influencer that steps in to advocate for the truth, there are hundreds or thousands that are trying to make a dollar off the pandemic or are trying to dissuade people that intervention is going to help,” she said.

Some of that unified messaging has already started, particularly as vaccines roll out in the US and the UK. Chris Christie, New Jersey’s former governor and a Trump adviser who was briefly hospitalized with the coronavirus, released a new ad encouraging wearing a mask. The Biden team has released an ad advocating for mask-wearing on Twitter.

Actors, nurses, and retirement home residents alike are making happy announcements about vaccinations. Online discourse consists not only of unsettling falsehoods about how vaccines work but also endless memes, jokes, and TikToks echoing the excitement of the light at the end of the tunnel.

“One of the big problems with the truth online as an object is that the truth is boring,” Donovan said. “The truth usually isn't riddled with scandal, and there's nothing that makes the truth something to share. It's almost as if when you share information that is truthful online, you're performing a public service.”