What does it mean to be an organic chicken?

The US Department of Agriculture and organic food advocates are locked in a fierce battle over just what "organic" means, specifically with regard to poultry welfare. How much living space should organic chickens be entitled to? How much access should they have to the outdoors?

While rules established in the twilight of the Obama administration would make life nicer for chickens raised organically — giving them more elbow room and time in the sun — the Trump administration has delayed implementation of these rules, perhaps indefinitely. And so the Organic Trade Association — the industry's lobbying group — has taken the USDA to court, seeking to force the agency to put the rules in place by Nov. 14.

A lot is at stake — and not just for the millions of birds involved. Chicken and egg producers say the new requirements would be far too expensive to implement, forcing some of them out of the organic business and reducing the overall supply available to consumers.

But animal rights groups and organic food advocates — who celebrated the arrival of the new rules and bemoaned that they didn't go far enough — say that the "organic" label implies a certain standard of living for animals. And if consumers think that standard isn't high enough, they could ultimately decide that buying organic just isn't worth it.

"That USDA organic seal needs to mean something to the consumer, and it needs to be significantly different from the alternatives, because people are paying more for organic products," Laura Batcha, CEO of the Organic Trade Association.

Without stricter rules, she and her members fear, "organic" eventually won't mean much at all to consumers. "We're looking forward to a judge weighing in," she said.

On the other side of the dispute is the National Chicken Council, a trade group for chicken farmers that is deeply concerned about the burden the rules would place on its members.

"Fundamentally, NCC is concerned that the proposed rule imposes unreasonable costs and requirements of doubtful benefit on organic farmers, presents grave risks to animal health in the face of an avian disease outbreak, and undermines ongoing international efforts to develop poultry welfare standards," the National Chicken Council wrote in a letter last year to the National Organic Program.

Another trade group, United Egg Producers, urged the USDA to withdraw the rules. "Farmers have made major capital investments in buildings, land and other assets, relying on USDA's previous" definition of organic, it said in a letter to the agency in June.

When it comes to organic meat, chicken is king. In 2016, sales of organic chicken (the most widely sold organic meat) shot up by 78% to $750 million and organic egg sales jumped by 11% $816 million. The poultry company Perdue acquired organic chicken producer Coleman Natural Foods in 2011.

Tyson Foods said earlier this year that the company would introduce organic chicken in July. "Organic is a very small space today, but it is growing," said Tyson's CEO, Tom Hayes, said at the time.

As things stand — and as they stood before the new rules were published in January — organic chickens have to be raised without genetic engineering, antibiotics, or added growth hormones. (In fact, all poultry is hormone-free.) They have to be given organic feed, and they have to have some form of access to the outdoors, though some farmers interpret that more generously than others.

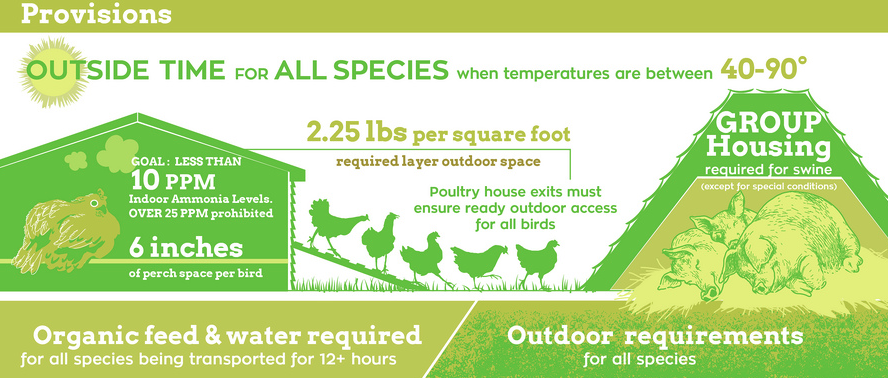

The new rules offer more specific protections. When it comes to poultry, "outdoor access must be provided when temperatures are between 40-90 degrees Fahrenheit," a summary of the rules stated.

"Outdoor space must be at least 50% soil covered with maximum vegetation suited to the time of year and climate," the summary stated, and "the vegetation must be maintained in a manner that does not provide harborage for rodents or other pests."

The implied costs are high: The USDA estimated that if all organic chicken and egg producers adopted the new standards, adding outdoor access and square footage would cost them up to $31 million per year for 15 years — an estimate that some in the industry describe as "deeply flawed" as they expect a bigger impact.

It is also possible, the agency noted, that the new standards might prompt some producers not to seek organic certification anymore, making it harder for mainstream consumers buy organic.

Meanwhile, the USDA said research showed that consumers are willing to pay $0.21 to $0.49 to give chickens outdoor access. A dozen organic eggs now costs about $3.70, while chicken breast now costs about $7.30 a pound. None of it is cheap, and already there's a glut of pricey cage-free eggs.

The Organic Trade Association is suing the USDA on behalf of chicken welfare: https://t.co/vdGZkFsNy6

The new standards — which had been in the works for a long time — were published by the USDA in January in the final hours of the Obama administration. "Consumers have specific expectations for organic livestock care, which includes outdoor access for poultry," the agency said.

But the rules, originally slated to take effect this spring, have been delayed repeatedly by the Trump-controlled USDA, as the industry fights back and the agency considers whether to scrap the changes altogether. The USDA in February put a hold on the new organic livestock rules, delaying the effective date to May 19. When May came, the agency pushed the deadline to Nov. 14 and invited the public to comment.

"The Trump administration has its hands full with a plethora of conflicts with the legislative branch of government," said Mark Kastel, co-founder of the organic watchdog group Cornucopia Institute. "I don't think anybody is holding their breath that it's going to go into effect."

So far, no court date has been set for the Organic Trade Association's lawsuit demanding that the rules become effective.

The USDA declined to comment, citing the active litigation. But lawmakers from agricultural states — on both sides of the aisle — have spoken out against the rules.

"Prices for consumers could rise, and animal health could be put at risk," said US Senator Pat Roberts (R-Kansas), chairman of the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry. He warned in January of the "serious potential to force organic farmers and ranchers out of business."

By mid-October, USDA was still reviewing comments and the animal welfare rules themselves, suggesting a less-than-bright outlook for the rule changes.

"This whole business of delaying the [rule's] effective date has generated much confusion amongst organic livestock and poultry farmers, and has created an unnecessary hardship on organic certification agencies," according to public comments submitted to USDA by the Ohio Ecological Food and Farm Association in June.

This frustrated the Organic Trade Association to the point of legal action. "This final rule has been 10 years in the making," said Batcha, the group's leader. "It should have happened well before" now.

"Organic" may be an everyday term now, especially for fruits and vegetables, but national standards in fact are a relatively recent addition to the American foodscape. It wasn't until 2002 that USDA organic standards replaced a confusing jumble of local rules. Pasture requirements for cattle were clarified years later, leaving poultry in the gray zone.

Boosting outdoor access for chickens was a priority issue for animal welfare advocates. Marty Irby, senior advisor at the Humane Society, said that implementing organic rules is one of his top issues — particularly the protections that apply to chickens, as those affect "more animal lives than any other regulation."

The prior rules didn't achieve consistency, various constituencies agreed. For example, it allowed both open land and enclosed porches to pass as outdoor space for organic chickens. This meant that some organic farmers were giving their chickens more freedom and space than others, creating "unfair competition and consumer confusion" about just what they were buying, a USDA presentation explained.

A Consumer Reports survey this year found that 83% of organic food consumers "think it’s highly important that organic eggs come from hens that were able to go outdoors, and have enough space to move around freely."

Some organic farmers worry that competitors are getting an organic certification even though their practices don't meet the spirit of organic farming. The new rules would make that spirit official: "Enclosed porches are not considered outdoors," officials declared.

The rule would also establish maximum "stocking densities" for the birds. Outdoors it would be 2.25 pounds of bird per square foot for laying hens and a tighter 5 pounds per square foot for broiler chickens; indoors, it would be 3 to 4.5 pounds of bird per square foot, depending on the type of housing, for laying hens and 5 pounds per square foot for broiler chickens.

Among the legislators who took issue with the rules was US Senator Debbie Stabenow (D-Michigan), ranking member of the agriculture committee. "I believe USDA missed an opportunity to do this in a way that did not risk unintended consequences," she said.

And the United Egg Producers said in a statement to BuzzFeed News: “USDA’s own analysis, in the proposed rule, assumed that about 45% of current organic egg production would be forced out of the organic business" and move to cage-free standards instead,

By contrast, the Organic Trade Association's complaint asserts that poultry producers "have made investments in reliance on anticipation of the implementation of the now delayed final rule." The lawsuit calls the delay "arbitrary" and "capricious."

"The government needs to move," said Batcha. In the current political environment, however, even she senses that "advancing the voluntary organic standards does not appear to be a priority."

The final rule.